-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for ŌĆ£ŌĆØ.

When a line goes quiet in a process plant, the clock gets very loud. Every hour of downtime is lost throughput, frustrated customers, and a lot of overtime on the maintenance floor. In the worst cases I have seen, shutdown budgets have ballooned by 30ŌĆō50 percent because a simple part was missing, a vendor slipped, or a bad assumption in the inventory plan collided with reality. Playbooks from industrial turnaround specialists and supply chain experts say the same thing: unavailability of critical equipment and spare parts can halt progress and extend downtime far beyond what anyone planned.

This article looks at critical spare parts through the lens of a plant shutdown, both planned and unplanned, and focuses on emergency inventory solutions that actually work in the field. The perspective is pragmatic: what to stock, where to keep it, how to protect your budget, and how to avoid being the person explaining to leadership why a twenty-dollar seal has a six-figure impact on schedule.

I am approaching this as an industrial automation engineer who has lived through shutdowns where the controls cabinets were ready, technicians were lined up, and everyone was waiting on a single drive, valve trim kit, or safety relay. The goal is to help you design a critical spares strategy so that when the plant must stop, your inventory keeps the project moving.

Industry guidance on plant shutdowns and turnarounds is consistent: these are complex, highŌĆærisk projects that must be managed like formal programs, not just extended maintenance jobs. Sources focused on industrial shutdowns emphasize that inadequate planning, missing parts, and weak logistics are among the top reasons schedules slip and budgets overrun. When the maintenance window is tight and dozens of contractors are on site, discovering that you are missing a bearing or a PLC I/O module is not an inconvenience; it is a delay measured in days.

Specialist providers that support shutdowns recommend planning major events 12ŌĆō18 months in advance, defining scope, locking change control, and confirming that all required materials are available and accessible before the first lockout-tagout is applied. One shutdown checklist highlights that nothing stops a multiŌĆæmillionŌĆædollar shutdown faster than a missing lowŌĆævalue item such as a gasket. Another playbook emphasizes that true shutdown cost includes lost profit from unproduced units, rental equipment, and startup inefficiencies, not just labor and material, and that poor planning can drive total cost 30ŌĆō50 percent above the original budget.

At the same time, MRO inventory data from industrial studies show that up to half of stocked items sit inactive for more than twelve months and as much as sixty percent of on-hand inventory exceeds a year of supply. Workers walk out of stores without the right material roughly a fifth of the time. That means many plants are paying heavily for the wrong spare parts while still not having the right ones when a shutdown or emergency hits. The challenge is not simply more inventory; it is smarter inventory focused on critical spares and backed by resilient emergency options.

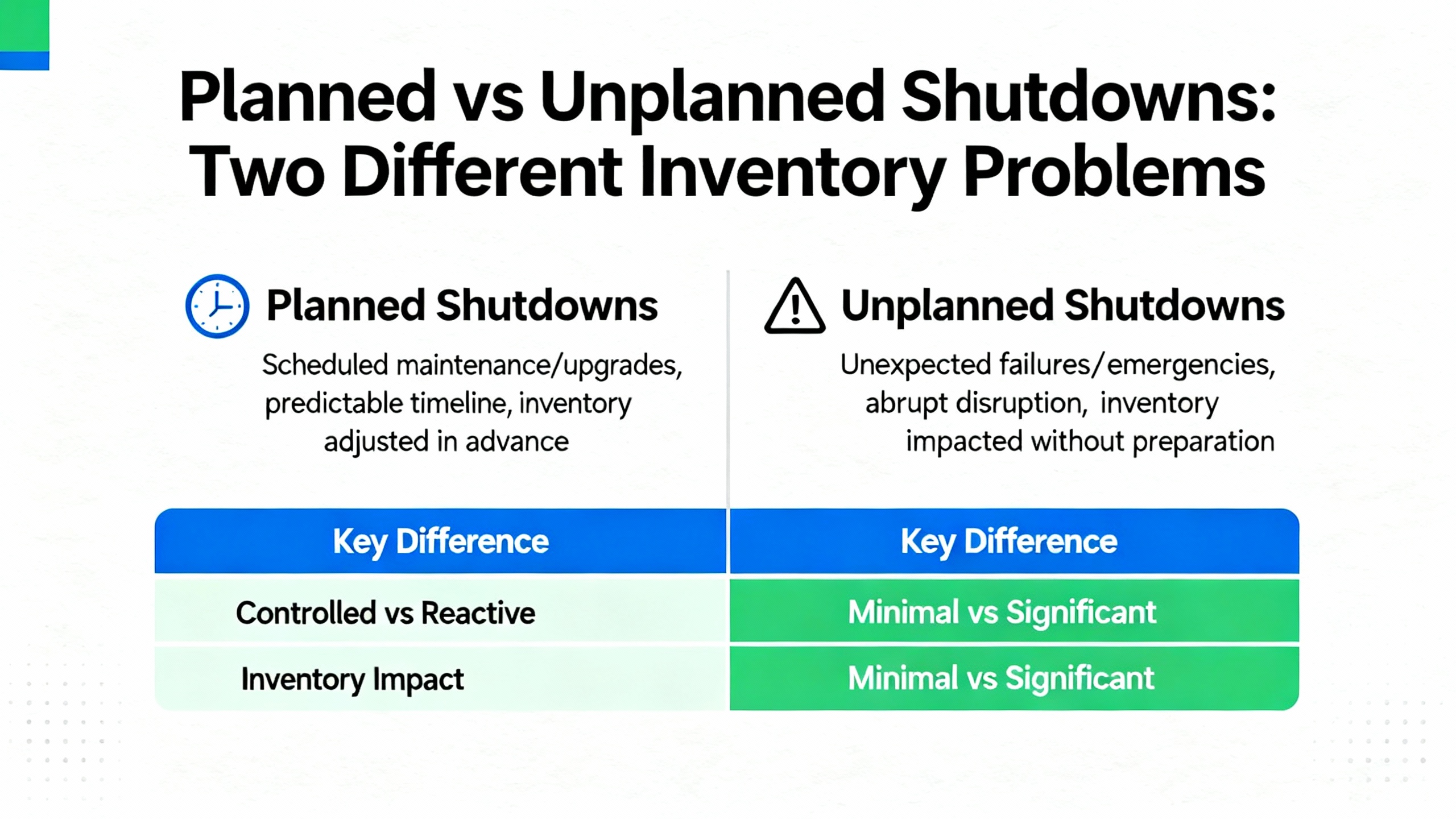

Not all downtime is created equal, and your spare parts strategy should reflect that.

Planned shutdowns, sometimes called turnarounds or outages, are scheduled pauses, often at least once a year. Guidance from plant shutdown resources describes these as periods where equipment is inspected, repaired, and upgraded to prevent unexpected failures. Planning typically starts at least a month in advance for smaller plants and up to 18ŌĆō24 months for large facilities, with formal phases, milestones, and assigned responsibilities. PreŌĆæshutdown tasks consistently include inspecting machinery, logging issues, checking the inventory of components, and ordering all required replacement parts several weeks ahead.

By contrast, unplanned shutdowns arise from power failures, sudden breakdowns, accidents, or upstream supply issues. Inventory management literature describes similar patterns in other sectors: planned inventory is forecastable and scheduled; unplanned inventory consists of adŌĆæhoc emergency purchases and contingency stock triggered by unexpected events. For plants, that might look like rush orders for a gearbox after a shaft shears or emergency buys of critical sensors during a quality investigation.

For planned shutdowns, the main risk is incomplete material readiness for a scope you already know. For unplanned shutdowns, the main risk is not having enough resilience in your inventory and supply chain to respond to surprises. Critical spares sit at the intersection of both: they are the parts that determine whether your planned work finishes on time and whether your unplanned events turn into long outages or short interruptions.

Not every expensive part is critical, and not every critical part is expensive. Across risk and resiliency guidance, several consistent criteria emerge that are useful for defining what belongs in your critical spare parts program.

First, consider safety and environmental impact. Any part whose failure can compromise a safety instrumented function, containment of hazardous material, or compliance with environmental permits deserves the highest priority. Frameworks such as Failure Modes and Effects Analysis and Business Impact Analysis are often recommended to identify where failures have the highest severity and regulatory consequences.

Second, focus on bottleneck equipment and single points of failure. Supply chain and mission continuity guidance repeatedly warn that singleŌĆæsource dependencies and singleŌĆæpath processes are major vulnerabilities. For a plant, that means production lines, utility systems, or controls infrastructure where one asset or one vendor can stop the entire operation. Spares for those assets have a different risk profile than spares for nonŌĆæcritical support equipment.

Third, look at lead time and availability. Supply chain resilience manuals describe how global disruptions, weather events, and labor issues can stretch lead times significantly. Items that require fabrication, involve specialized materials, or come from limited suppliers are more likely to be unavailable during an emergency. In medical and public health supply chains, this is one reason governments maintain strategic stockpiles of critical products rather than relying purely on routine deliveries.

Fourth, quantify operational and financial impact. Some inventory management sources use ABC classification based on annual consumption value, where a small fraction of items represent the majority of spend. For critical spares, a similar idea applies, but the priority is not just cost; it is the dollar impact of a day of downtime versus the cost of holding the part. Industries that analyzed this tradeoff have found that inventory optimization can reduce unplanned downtime caused by missing parts by up to half while also cutting overall inventory costs.

The table below summarizes these criteria in a way that can be applied directly to industrial automation and control assets.

| Criterion | Practical question for the plant | Typical examples |

|---|---|---|

| Safety and environment | Could failure of this part create a safety or environmental incident? | Safety relays, SILŌĆærated sensors, relief valves, emergency stop components |

| Bottleneck and single point | Does this part sit on equipment that can stop a whole line or utility if it fails? | Main PLC CPU, network switches, critical pumps, compressors, MCC buckets |

| Lead time and uniqueness | Is the lead time long, vendor base narrow, or configuration unique to this plant? | Custom gearboxes, OEMŌĆæspecific drives, specialized valve trims |

| Operational and financial | Does a missing spare for this part risk high downtime cost relative to its carrying cost? | ModerateŌĆæcost but frequently failing transmitters, encoders, actuator kits |

When a part scores high on at least two of these dimensions, it usually belongs in your critical spares list.

Once you have a clear definition of critical spares, the next step is to embed them into shutdown planning. Turnaround guidance from maintenance playbooks, industrial service providers, and equipment manufacturers highlight several practices that consistently separate smooth shutdowns from chaotic ones.

The first building block is a formal riskŌĆæbased equipment assessment. Practices from risk and resiliency institutes suggest periodic risk reviews that map dependencies on power, water, and key supply routes, and tools like risk heat maps that plot likelihood versus impact. In a plant context, that means assembling maintenance, operations, and engineering to walk through critical assets, identify failure modes, and score them by severity and downtime impact. Structured tools such as Failure Modes and Effects Analysis or Business Impact Analysis are often recommended to prioritize where limited resources should go.

Next, connect this risk view to your spare parts. For each critical asset, build or clean up the bill of materials down to the level of components that actually fail during shutdown scopes: seals, bearings, belts, drives, I/O cards, HMI panels, and so on. Shutdown playbooks stress that work packages should contain a complete bill of materials and that missing small parts are a common reason technicians cannot complete a job. Plant shutdown articles also emphasize using checklists for systems like blowers, rotary valves, filters, controls, and silos so no component is overlooked.

After that, tier your spares by criticality and service level. Inventory management references frequently recommend tiered safety stock or min/max levels, especially for topŌĆæselling or lifeŌĆæcritical items, and dynamic reorder points based on demand and lead time. For a plant, you can adapt that logic so that Tier 1 parts are true showstoppers for safety or production and must be stocked on site; Tier 2 parts may be stocked in reduced quantities or secured through reliable nearŌĆæsite suppliers; Tier 3 parts can remain on longer lead times, with plans for substitution or temporary workarounds.

Then, embed spares planning into the shutdown schedule. Advanced turnaround frameworks divide shutdowns into phases such as Initiation, Planning, Scheduling, Execution, and CloseŌĆæOut. Early phases, often starting a year or more ahead for large facilities, are where you identify longŌĆælead items and place orders. Best practice is to freeze shutdown scope months before execution so that procurement and kitting can catch up. ShutŌĆædown guidance warns that late additions to scope without formal change control drive scope creep, cost increases, and schedule slip.

Finally, stage and kit materials for execution. Several sources emphasize kitting as a way to protect productivity: instead of sending technicians to walk the warehouse with a paper pick list, assemble kits by work order with all parts, gaskets, and consumables preŌĆæpacked. Then, stage these kits in laydown areas near the job site before the shutdown begins. Combined with a clear shutdown checklist and daily coordination meetings, this reduces waste, rework, and time lost hunting for parts.

Even with robust planning, unexpected failures during or between shutdowns are inevitable. Emergency inventory solutions are about limiting the damage when that happens.

Supply chain resilience guidance recommends a blend of safety stock and justŌĆæinŌĆæcase strategies for critical items, monitored through clear metrics such as lead times, supplier reliability, and inventory turns. In MRO environments, experts point out that a significant share of inventory is inactive while critical items remain at risk of stockout. One practical approach is to identify items that can play a double role, supporting both daily operations and emergency needs. Examples from emergency preparedness discussions include wireless communication gear, power systems, and safety markers that are useful every day but become essential during incidents.

For critical spares, doubleŌĆæduty inventory might mean stocking additional units of standard drives used across several conveyors or standardizing on a limited set of control hardware families so that spares are interchangeable. This increases the chance that your emergency stock is both used regularly enough to avoid obsolescence and available for the next unplanned outage.

Many supply chain disruptions in recent years have shown how vulnerable singleŌĆæsource strategies can be. Risk and continuity guidance aimed at universities and contractors recommend vendor risk assessments, identification of critical singleŌĆæsource dependencies, and multiŌĆæsource procurement strategies that add regional and local suppliers to reduce transportation risks. They also stress the value of preferred vendor lists with preŌĆævetted secondary suppliers, so switching in an emergency is an execution step, not a procurement project.

Emergency inventory solutions on the supplier side often include preŌĆænegotiated agreements that specify surge capacity, expedited shipping during crises, and clear recovery timelines. Government emergency preparedness guidance encourages formal memoranda or agreements that define how resources will be shared, how shortages will be communicated, and what allocation rules apply when supply is constrained. In an industrial context, similar agreements with key OEMs, distributors, and integrators can ensure priority access to critical spares during broader disruptions.

Across industries, there is strong alignment on the value of realŌĆætime inventory visibility. Multichannel inventory management platforms, hospital inventory systems, medical supply chain tools, and emergency stock solutions all point to the same basic capabilities: accurate stock data, centralized records, and automated alerts.

Common technical enablers include barcodes, RFID tags, and cloudŌĆæbased inventory systems that track item counts, serial numbers, and locations. These systems reduce manual data entry, keep records synchronized with actual usage, and enable cycle counting instead of disruptive full physical counts. One brewer reduced excess stock by a quarter by tightening planning cycles and adjusting reorder points based on actual consumption, and a cosmetics brand cut stockouts by forty percent after adopting a unified dashboard.

For critical spares in plants, similar principles apply. A computerized maintenance management system or inventory module can serve as the digital backbone for work orders, asset histories, and spare parts data. When linked to scanners in the storeroom and integrated with purchasing, it can issue alerts when critical items fall below minimum levels, track where parts are used, and support automated reordering. In emergency inventory guidance, visibility down to the aisle or bin level is considered essential so responders can locate and deploy supplies quickly; the same is true when a crew is trying to find a specific drive or sensor under time pressure.

Some supply chain resilience research highlights vendorŌĆæmanaged inventory and consignment inventory as tools to manage complexity and cost. Under vendorŌĆæmanaged inventory, the supplier takes responsibility for maintaining agreed stock levels at the customerŌĆÖs site. Under consignment inventory, the supplier owns the stock until the customer uses it.

In healthcare, these models have been used to keep expensive products available while freeing working capital. The same concepts can be applied cautiously to industrial spares. Advantages include better alignment between supplier product knowledge and stocking decisions, and smoother rotation of items with limited shelf life. However, studies also warn about reduced visibility and control for the end user, risks of expired or misplaced stock, and the possibility that the same ŌĆ£promisedŌĆØ inventory is effectively counted against multiple customersŌĆÖ emergency plans.

If you consider these models for critical spares, the risk management guidance is clear: they require high trust, defined performance expectations, transparent data sharing, and explicit discussion of how emergency situations will be handled. They should complement, not replace, a core onŌĆæsite inventory of the highestŌĆærisk parts.

Translating best practices into a running facility is always the hard part. Here is how I typically approach critical spares and emergency inventory when working with an existing plant that is planning recurring shutdowns.

The first phase is a structured risk and asset review. Over several working sessions, I sit down with maintenance, operations, and safety to map out the plantŌĆÖs most critical processes, from incoming utilities through production lines to outbound handling. Using a simple severity and likelihood matrix informed by guidance from risk and resiliency institutes, we identify where failures could cause the most harm in terms of safety, environment, and production loss. For those assets, we then trace which spare parts would be needed during a planned shutdown or an unplanned outage.

The second phase is an inventory reality check. Using the existing inventory records, I compare what the system says is on hand with what is physically present through focused cycle counts. Studies on MRO inventory repeatedly show that records are often inaccurate because items are moved, ŌĆ£stashed,ŌĆØ or miscounted. Rather than shutting the plant down for a full physical count, I target the areas with critical spares and high spend first. This immediately reveals obsolete parts, duplicates, and gaps where we have zero stock of an item the shutdown scope assumes will be replaced.

The third phase is integration with shutdown planning. For the next planned outage, I work with the turnaround planners to embed a critical spares review into the scope freeze process. Each major job gets a work package with a clear description, safety requirements, and a complete bill of materials. LongŌĆælead items are identified early; orders are placed with enough buffer to absorb typical delivery variability. For higherŌĆærisk parts, we confirm supplier capacity and discuss contingency plans if deliveries slip. Kits are assembled for critical jobs and staged in controlled laydown areas before the shutdown starts.

The fourth phase is emergency readiness outside the shutdown window. Using concepts from emergency inventory management and supply chain resilience, I define a small but robust set of safety stock for parts whose absence would cause immediate and severe downtime. These items are given strict min/max levels, stored in clearly marked locations, and included in more frequent cycle counts. Alongside this, I review supplier relationships to ensure we have at least one alternative source for critical components, with contact information, lead times, and afterŌĆæhours procedures documented and accessible.

The fifth phase is continuous monitoring and improvement. After each shutdown or major unplanned event, I lead a postŌĆæevent review that specifically looks at spare parts performance. Questions include whether any jobs were delayed by missing or incorrect parts, whether any emergency orders were placed, and whether stocked critical spares turned out to be unnecessary or obsolete. Findings are fed back into the risk assessments, bills of materials, and inventory parameters. This aligns with recommendations from shutdown bestŌĆæpractice articles and emergency preparedness manuals that stress afterŌĆæaction reviews as a central tool for learning.

Critical spares and emergency inventory solutions do not live in the storeroom; they live in governance and culture. Organizations that handle disruptions well tend to treat resilience as an ongoing discipline, not a oneŌĆæoff project.

Many sources recommend annual or even more frequent risk and inventory reviews. For small operations, experts say a focused review can be done in a few hours, while larger organizations may need more systematic efforts. Formal governance structures, such as steering committees or mission continuity plan owners, ensure that decisions about how much risk to accept, what to stock, and which suppliers to depend on are made consciously rather than by default.

Training is also essential. Inventory systems and predictive tools add little value if technicians bypass them or if planners do not trust the data. Hospital and emergency response best practices emphasize regular drills, not just of response actions but also of inventory procedures, so staff know where supplies are, how to access them, and how to keep records accurate under stress. In plants, a practical equivalent is to include the stores team, engineers, and contractors in shutdown simulations and daily progress meetings so that issues with parts are surfaced and resolved early.

Finally, culture matters. Guidance for contractors and businesses dealing with crises highlights that a culture of innovation and adaptation helps teams propose improvements and adjust quickly when conditions change. In the context of critical spares, that means encouraging technicians to flag recurring failures, inviting storeroom staff into risk discussions, and being willing to refine stocking strategies as new data comes in.

There is no universal number, but several references suggest combining impact analysis with evidenceŌĆæbased inventory models. Start by quantifying the downtime cost for critical equipment, then compare this to the cost of holding specific spares. Use models that consider demand rates, lead times, and holding costs to set safety stock levels. The goal is to avoid both overstock, which ties up capital and storage, and stockouts, which amplify downtime.

VendorŌĆæmanaged and consignment arrangements can be part of the solution, especially for expensive or fastŌĆæexpiring items. However, research on these models warns about reduced visibility and potential shortages during emergencies. For parts with very high safety or production impact, onŌĆæsite stock under your direct control is usually warranted, with supplier models used to complement, not replace, that core buffer.

Risk and resiliency guidance recommends at least an annual review, with additional reviews after major shutdowns or disruptions. Use these reviews to adjust for equipment changes, new failure data, supplier performance, and lessons learned. If your plant is undergoing frequent changes or operating in a volatile supply environment, more frequent reviews may be justified.

In the end, a shutdown always exposes how seriously a plant has treated its spare parts strategy. When the floor is crowded with contractors and the line is cold, there is no substitute for having the right critical spares on hand and a resilient emergency inventory plan behind them. As someone who has stood in that engine room when things did not go as planned, I can say that a wellŌĆædesigned critical spares program is one of the most effective tools you have for turning shutdowns from chaotic fire drills into controlled, valueŌĆæadding projects.

Leave Your Comment