-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for ŌĆ£ŌĆØ.

When a plant is quiet and stable, no one thinks about how fast you can get a new flame detector on a tank farm or a replacement valve actuator on a fire-water line. When alarms are going off, smoke is in the corridor, or a generator refuses to start in the dark, that deployment speed becomes the difference between a controlled incident and a full-blown emergency.

As an automation engineer who spends a lot of time in electrical rooms, rooftops, and nasty corners of process plants, I have learned that ŌĆ£emergency sensor and actuator supplyŌĆØ is not just a purchasing problem. It is an engineering discipline that ties together codes like NFPA 101 and NFPA 110, OSHA fire detection rules, intrinsically safe deployment checklists, and the nuts and bolts of sensors, actuators, and power systems.

This article walks through how to design your field device strategy so you can deploy or replace critical sensors and actuators fast, without cutting corners on safety or compliance.

Emergency in this context does not only mean flames and sirens. It means any situation where the absence or malfunction of a sensor or actuator materially increases risk to people or critical assets.

Guidance drawn from NFPA 101 Life Safety Code, emergency lighting best practices, and OSHA fire detection standards points to several recurring themes. Life-safety systems such as emergency and exit lights, fire detectors, and controlled egress doors must keep working when normal power fails, and they must be installed and tested in very specific ways. For example, NFPA 101 requires emergency lighting along paths of egress to come on automatically at power loss and to provide defined illumination levels for at least about ninety minutes. OSHAŌĆÖs fire detection rules require detectors to be selected and placed according to the fuels present and the environment they protect, and they must be protected from corrosion, mechanical damage, and improper mounting.

The same mindset applies to the sensors and actuators that sit behind the scenes: guard switches on machine doors, valve actuators on fuel lines, vibration sensors on emergency generators, position sensors on dampers, and pressure switches on suppression systems. If any of those devices fail or cannot be deployed quickly in an emergency, every assumption in your risk assessment starts to fall apart.

Rapid field deployment is therefore about three intertwined capabilities. You need the right devices on hand and correctly specified. You need the infrastructure and procedures to power, mount, and test them safely under stress. And you need documentation and records that satisfy authorities having jurisdiction and your own internal safety expectations.

A sensor turns a physical condition into data. In emergency and life-safety systems, that condition may be as obvious as smoke, heat, or open flame, or as subtle as high-frequency bearing vibration that hints at an impending generator failure.

Industrial maintenance guidance from UpKeep and research published in the journal Sensors emphasize that sensors underpin early fault detection, failure detection, and integration with computerized maintenance management systems. OSHA and life-safety codes add another layer: certain sensor types and locations are effectively mandated by law.

Fire detection guidance from OSHA highlights three foundational detector types.

Smoke detectors, using ionization or photoelectric principles, are designed to pick up fires in the smoldering or early flame stages, particularly when solid fuels like wood, paper, fabric, and plastics are present. OSHA notes that these detectors work well in clean indoor areas with low ceilings such as offices, closets, and restrooms, where background dust and air movement are low. The upside is very early warning in normal occupancies. The trade-off is a high nuisance-alarm risk in dirty, dusty, or smoky environments, in kitchens, in high-airflow areas, and in many outdoor locations, where they are not recommended.

Heat detectors come into their own in harsher conditions. OSHA identifies them as ideal in spaces where flammable gases and liquids are handled, or anywhere a fire will quickly cause a large temperature change. They are suitable for dirty or smoky environments, manufacturing areas with vapors or fumes, and rooms where particles of combustion are normally present such as kitchens, furnace rooms, utility rooms, and garages. You give up some early detection compared with smoke detectors, but you gain much better reliability where smoke and dust are part of normal life.

Flame detectors are specialized devices for high-risk, open, or high-ceiling locations. OSHA guidance points to warehouses, auditoriums, outdoor or semi-enclosed areas with significant wind or drafts, petrochemical production, fuel storage, paint shops, and solvent areas as typical applications. In these spaces, smoke and heat may not reach a detector in time, while a flame detector can see the radiant energy from a rapidly developing fire. The upside is very fast detection of fast-burning fires in difficult geometries. The downside is higher cost and a need for careful line-of-sight design and shielding from false sources.

Beyond fire, condition-monitoring sensors can quietly prevent an emergency from ever happening. Technical notes from Renke on industrial vibration monitoring explain why using a vibration sensor with frequency capability up to around 12,000 Hz gives better coverage of high-frequency signatures from early bearing defects, gear mesh issues, and resonance. Lower-bandwidth sensors may only pick up late-stage faults when damage is already severe, while high-frequency sensors enable intervention before a failure cascades into loss of power, fire, or release of hazardous material.

In modern emergency support systems, these sensors are tied into controllers, safety PLCs, and CMMS platforms so that abnormal conditions create clear, actionable tasks rather than unlabeled blinking lights.

If sensors tell you what is happening, actuators do something about it. An actuator converts energy plus an electrical control signal into physical motion. In emergency applications, that motion might be closing a valve to isolate a fuel source, opening a damper to release smoke, tripping a safety switch to disconnect power, or moving a barrier into a safe position.

Guidance from Intuz on IoT actuators and from Indelac and Venus Automation on industrial actuators and safety switches gives a clear picture of the common choices and their behavior under stress.

Pneumatic actuators use compressed air to produce torque or thrust. Indelac notes that they typically operate with supply pressures around normal plant air ranges and provide a very robust, high-cycle solution with a true one hundred percent duty cycle; a pneumatic actuator can be stalled indefinitely without damage. They are also inherently explosion-proof, making them attractive in hazardous locations where flammable gases or vapors are present. Building a spring-return arrangement is straightforward, so defining a fail-open or fail-closed position for an emergency becomes simple. The trade-off is that they depend on a clean, dry compressed-air supply and associated accessories, and air lines can be vulnerable to freezing at low temperatures if dew point and condensation are not managed.

Electric actuators use electric motors and gearing to drive valves or other mechanisms. They integrate very naturally with electronic control systems and modulating control, as Indelac notes, and are ideal when precise positioning and ease of integration outweigh other concerns. They generally have more limited duty cycles in standard versions, often around a quarter of the time at full load before they must rest to avoid overheating, and they do not tolerate prolonged stall conditions. In hazardous areas, they require appropriately classified enclosures rather than relying on inherent explosion-proof behavior. Fail-safe action commonly depends on battery backup or electrohydraulic spring-return mechanisms, rather than a simple metal spring.

Safety switches and non-contact safety sensors provide another category of actuation in emergency contexts. Venus Automation describes devices such as disconnect switches, residual current devices, enabling switches, limit switches, foot switches, and non-contact coded sensors as core elements of industrial safety systems. These devices, often combined with safety relays or safety PLCs, ensure that machines operate only when guards are closed, operators are in safe positions, or control signals are valid. Stainless steel housings, high ingress protection ratings, and safety ratings up to SIL 3 or Performance Level e make them suitable for harsh hygienic environments and high-risk zones.

In an emergency deployment, you need to know which actuator type matches your available power sources, environmental conditions, required fail-safe position, and response time. That decision is significantly easier if you have already documented preferred devices and their limitations.

Emergency events rarely happen under full normal lighting and perfectly stable grid power. Life-safety codes treat emergency lighting and emergency power as foundational; for field devices, these same systems are the difference between a replaced detector that works and one that is dark and silent when the building needs it.

NFPA 101 Life Safety Code and guidance from Koorsen Fire & Security describe emergency lighting systems that automatically provide illumination when normal power fails. The code requires that means of egress, including exits, stairs, aisles, corridors, ramps, escalators, walkways, and exit discharge areas, receive emergency illumination. Performance requirements specify that when normal lighting fails, emergency lighting must provide an average of about one foot-candle along the path of egress, with no point dropping below a tenth of a foot-candle during the first ninety minutes. After that period, illumination may decline but must still average at least roughly 0.06 foot-candle, with a maximum-to-minimum ratio no greater than about forty to one, to avoid deep shadow pockets.

Van MeterŌĆÖs emergency lighting guidance, reflecting IBC and NFPA expectations, reinforces that emergency egress illumination must last at least ninety minutes, whether powered by local batteries, central battery systems, or onsite generators. NFPA 70, the National Electrical Code, requires that battery-supplied fixture voltage stays within a defined window over that interval.

Testing routines are strict. NFPA 101 expects every emergency light to be tested at least every thirty days for about thirty seconds and once per year for the full ninety minutes, with all units required to remain fully operational. Battery-operated self-testing units must still be visually inspected at regular intervals, and any computer-controlled testing system must be able to produce reports and maintain written records for the authority having jurisdiction.

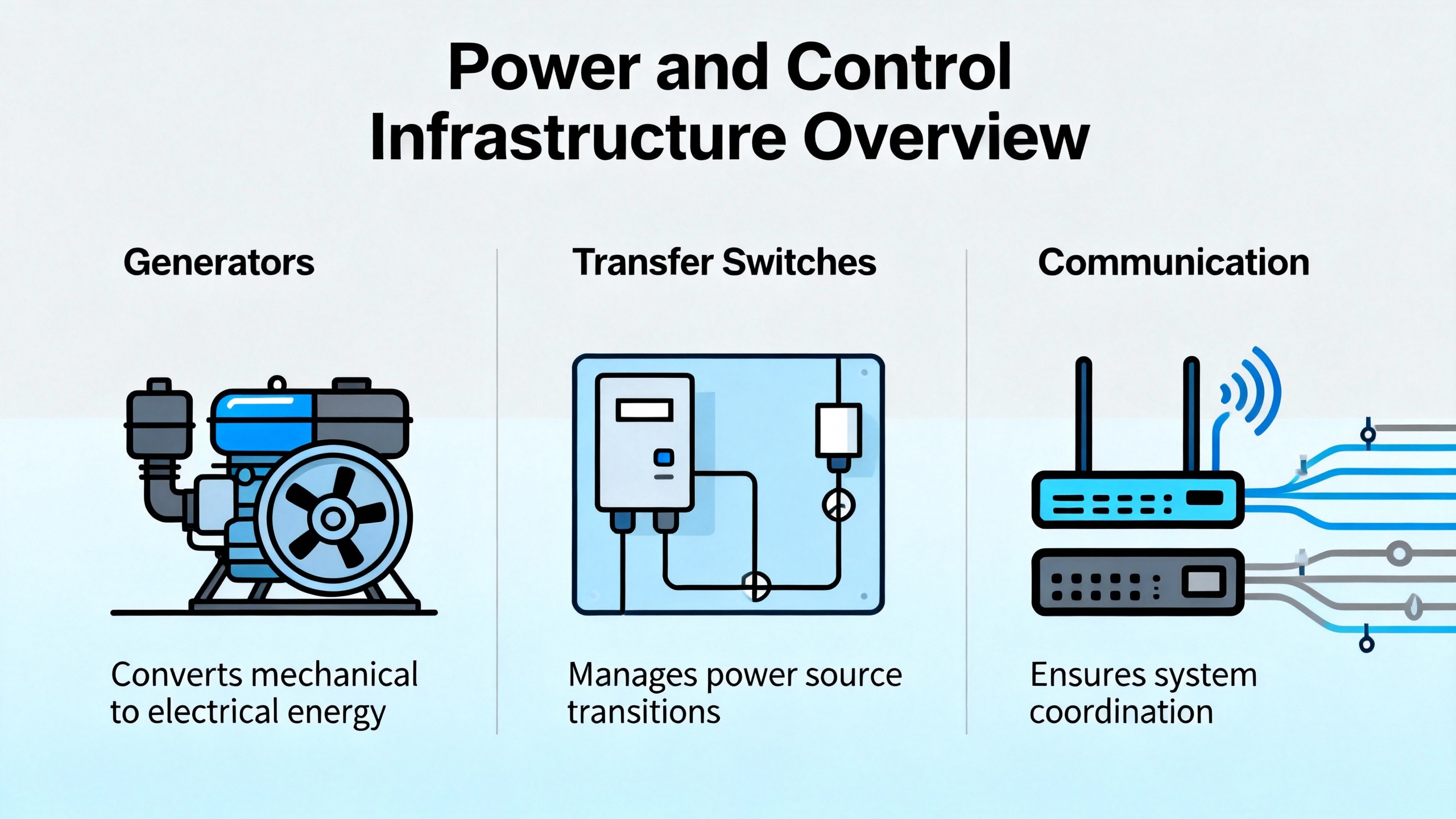

Those same emergency power branches often feed sensors and actuators critical to emergency response: door locks that must release under fire conditions, smoke control actuators, or detectors that must remain powered even when normal lighting circuits are offline. NFPA 110 defines the performance and testing requirements for emergency and standby power supply systems, including generators and automatic transfer switches that serve these loads. Curtis Power Solutions highlights that during the 2003 Northeast blackout, about one fifth of generators failed to start or failed shortly after starting, with dead or weak batteries as the leading cause. NFPA 110 addresses this risk by requiring monthly generator testing with available facility loads, and diesel sets must be exercised at meaningful load levels. When building load cannot provide adequate loading, the standard calls for an annual load bank test at progressively higher load fractions.

From a rapid deployment standpoint, this means you cannot treat emergency power and emergency sensors or actuators as separate problems. Before you declare a new field device ŌĆ£ready,ŌĆØ you need to confirm that it is connected to a power source that will still be alive ninety minutes into a power failure and that the generator, transfer switches, and batteries supporting that branch have been tested according to NFPA 110 and any relevant Joint Commission or local requirements.

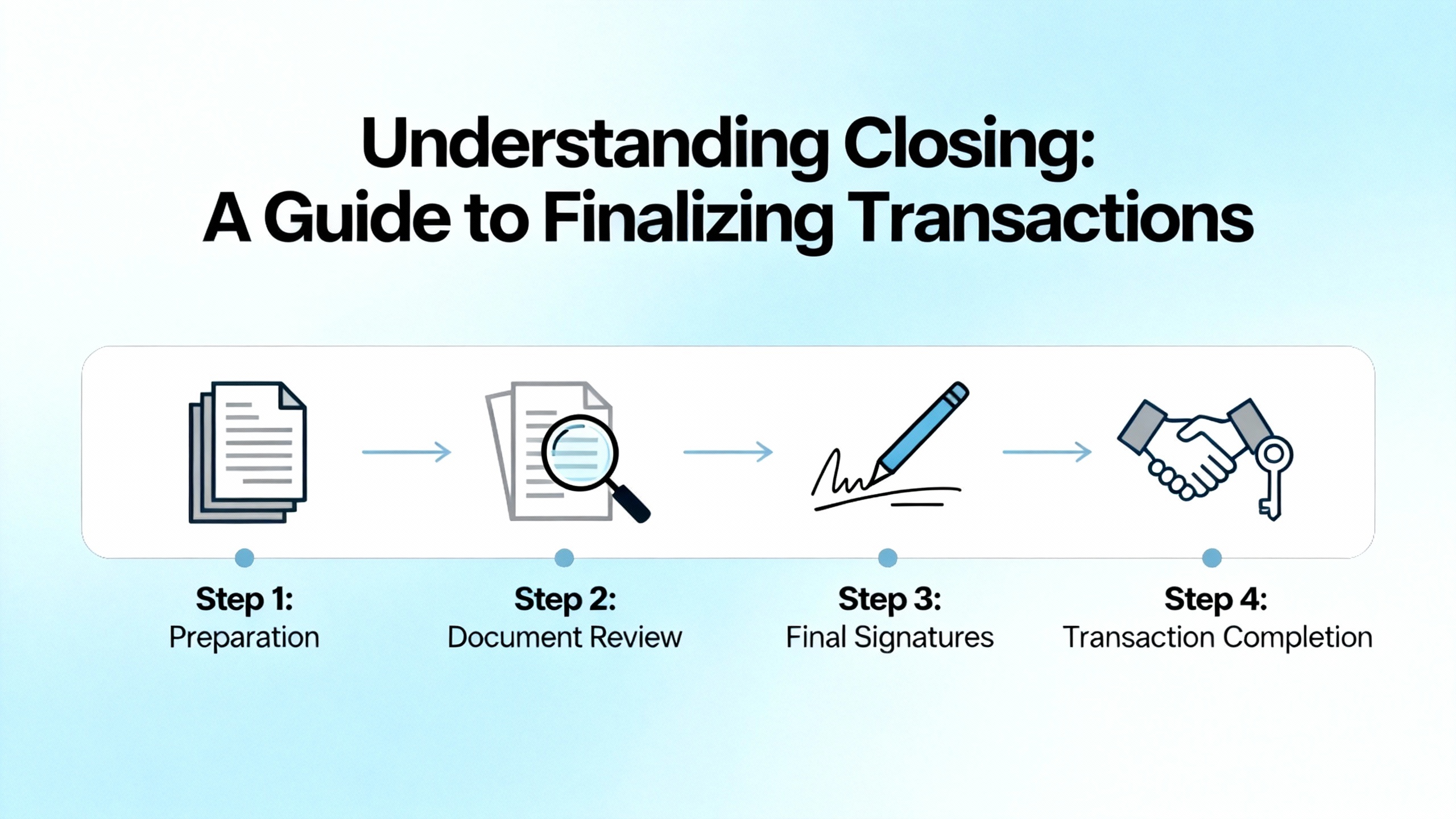

There is no such thing as rapid deployment if every incident starts with a blank sheet of paper. The facilities that handle emergencies well build their sensor and actuator supply around clear rules, checklists, and documented selections.

Emergency lighting maintenance resources from Yadkin Fire & Safety and Zapium show what this looks like for luminaires and exit signs. They recommend written inspection and maintenance schedules, logs of test dates and results, and a small inventory of common spare parts such as batteries, lamps or LED boards, covers, and test switches. Applying the same discipline to field sensors and actuators means keeping a defined stock of the devices that are both critical and likely to fail, along with manufacturer documentation, datasheets, and certifications.

In hazardous areas, an intrinsically safe deployment checklist is non-negotiable. Intrinsically safe guidance emphasizes verifying that every device carries the correct ATEX, IECEx, UL, or CSA marking for the zone or division where it will be used, matching zone and gas group markings, and retaining traceable documentation. Accessories such as chargers, holsters, and mounts must also be certified; a non-approved accessory can void the intrinsic safety rating and create an ignition risk. Devices should be inspected for physical integrity, correct sealing, and intact labels, and must be fully charged and functionally tested before they ever see the classified area.

The more of that work you do on a calm day, the less you are improvising under pressure. When your team knows that ŌĆ£if a Class I Division 1 gas detector fails, we replace it with this exact certified model and this certified charger, and we follow this checklist,ŌĆØ deployment time shrinks dramatically while compliance confidence goes up.

When something fails in a live plant, your first job is not to hang a new sensor. Guidance on handling electrical emergencies emphasizes a calm, safety-first approach. The initial response is to assess the situation, look for signs of electrical trouble such as sparks or burning smells, and identify the source. Power should be shut off at panels or breakers only if it is safe to do so, and water near energized equipment is a serious red flag. Electrical fires require a Class C-rated extinguisher; anything larger demands evacuation and professional firefighters.

That mindset carries into field device work. Before you touch a failed fire detector, a seized actuator, or a damaged safety switch, you ensure the area is safe, circuits are de-energized where required, and lockout/tagout is applied. In emergencies that involve water, conductive dust, or unknown damage, untrained personnel should not attempt repairs; certified electricians and qualified technicians are the right resource.

Only once the area is stable and safe do you move to selection and installation.

In a real event, you rarely have time for exhaustive trade studies. You need decision rules that compress the selection process into a few well-understood questions.

For detection, OSHAŌĆÖs fire detection guidance is a good foundation. You ask what is burning, what the environment looks like, and how air moves. If the area is a clean office with paper and plastic furnishings, a smoke detector may be appropriate. If it is a paint mixing room with vapors and routine smoke or dust, a heat detector is likely safer. For a high-bay fuel storage area exposed to wind, a flame detector may be the only realistic option. You also consider whether the replacement needs weather or corrosion protection such as canopies, hoods, or non-corrosive coatings, and how you will protect it from mechanical impact.

For condition monitoring and emergency support equipment such as generators, you ask whether a simple low-frequency vibration sensor is enough or whether a wider-bandwidth device is justified. RenkeŌĆÖs focus on higher frequency ranges points out that if you are trying to catch early bearing faults on critical rotating machinery that supports life-safety loads, a twelve kilohertz sensor is not luxury; it can be the difference between catching a defect during a scheduled shutdown and discovering it when the generator fails to carry the life-safety branch.

For actuators, you decide between pneumatic and electric options based on power availability, hazard classification, duty cycle, and fail-safe requirements. IndelacŌĆÖs comparison suggests that in explosive gas or vapor areas where good compressed air is available, pneumatic actuators are often the safer and simpler emergency choice. Electric actuators become attractive when air is unavailable or precise electronic control is critical, provided that enclosures meet hazardous area classifications where necessary and duty cycles and stall behavior are respected.

In hazardous locations, the intrinsically safe checklist becomes your guardrail. You confirm that the replacement deviceŌĆÖs markings match the original design basis, including zone or division, gas group, and temperature class, and that its documentation is current. You reject any device with a missing or illegible certification label, as intrinsically safe guidance recommends immediate removal from service in such cases. You verify that all accessories are approved for intrinsic safety and that charging or configuration is done outside the hazardous area if required.

Once the device is chosen, rapid deployment does not mean sloppy installation. You still follow the same mechanical and electrical rules the standards require.

OSHAŌĆÖs detector guidance insists that detectors be securely mounted to solid surfaces, supported independently of their wiring or tubing so that conductors do not carry mechanical stress. They must be located away from sources of physical damage or protected with cages or guards. Spacing and placement must follow design data, including field experience, engineering surveys, manufacturer recommendations, and testing laboratory listings. Practical placement rules include covering each room, storage area, hallway, closet, shaft, stairwell, and enclosed space with at least one detector, adding more when spacing exceeds the manufacturerŌĆÖs rated distance, locating detectors near the center of ceilings when only one is used, and placing smoke detectors at least about three feet away from ceiling fans.

Emergency lighting testing practices provide a good template for how to treat new or replaced devices. Yadkin Fire & Safety and Koorsen describe monthly quick tests and annual full-duration tests for luminaires, documenting whether units remain illuminated for the full test duration and replacing batteries or fixtures that fail. Translating that to sensors and actuators means simulating normal and fault conditions, verifying that the device responds correctly, and logging those results. For a detector, that might be a functional test that verifies activation on a test signal and restoration afterward. For an actuator, it might be a full-stroke motion under load, confirming that the device reaches the intended fail-safe position when power is removed.

Curtis Power Solutions and NFPA 110 remind us that emergency power components require similar documented testing: monthly generator runs, periodic transfer switch exercise, and periodic long-duration tests. ZapiumŌĆÖs emergency lighting checklist further stresses documenting test dates, technician names, voltage readings, failures, and corrective actions. All of this aligns with NFPAŌĆÖs requirement to maintain written records for inspection.

A new sensor or actuator is not fully deployed until your records reflect its installation, test results, and the next scheduled inspection. That discipline is what keeps emergency readiness from eroding between incidents.

Rapid deployment gets especially complicated in hazardous or hygienic environments. Here, every shortcut has the potential to create a worse hazard than the one you are trying to mitigate.

Intrinsically safe deployment guidance makes it clear that deploying energy-emitting devices in ATEX or IECEx classified zones is not a paperwork formality. Every radio, flashlight, tablet, charger, and sensor must be certified for the exact zone or division. Documentation must show that labeling is valid and that certifications have not expired. Devices are visually inspected for cracks, corrosion, missing seals, and damaged ports or buttons. Accessories such as cases or holsters must not cover safety or certification labels. Battery charging is done per strict rules, often outside the hazardous area, and only with certified chargers.

Venus AutomationŌĆÖs discussion of stainless steel safety switches and sensors in washdown environments adds another dimension. For food, pharmaceutical, and chemical plants, corrosion resistance, high ingress protection (up to IP69K), and appropriate safety ratings are non-negotiable. That applies equally in emergency deployment; grabbing a standard mild-steel switch for a caustic washdown area may give you a quick restart but sets up early failure.

IndelacŌĆÖs and IntuzŌĆÖs actuator guidance similarly caution that temperature capability, duty cycle, and environmental sealing must be considered. Pneumatic actuators can be extended with special seals and greases for low temperatures, but accessories may limit the range, and condensation can freeze air lines. Electric actuators must be sealed properly outdoors and may need heaters to prevent internal condensation. In emergency deployments, those environmental details matter; a device that works in the first hour but fails in the first freeze has not really solved your problem.

Intrinsically safe and hazardous-area devices should be inspected before deployment, immediately after deployment, and at least every few months as part of routine safety audits, as intrinsically safe checklists recommend. Any device with worn or unreadable labels should be removed from service. That may feel harsh in the middle of a rush, but it is exactly how you avoid turning an emergency fix into a future ignition source.

Emergency sensors and actuators are useless if the infrastructure behind them is weak. The emergency power and control backbone is as much a part of your rapid deployment strategy as boxes of spare devices.

NFPA 110 lays out the installation, maintenance, operation, and testing requirements for emergency power supply systems. Curtis Power Solutions explains that diesel generator sets must be tested monthly at not less than a defined fraction of their nameplate rating and must undergo annual load bank tests when building load cannot provide adequate loading. Transfer switches and paralleling gear require formal inspection and maintenance programs, including frequent operation, periodic major maintenance, infrared or temperature scanning for hot spots, and insulation resistance testing.

Joint Commission guidance for healthcare facilities goes further, calling for monthly generator and transfer switch testing and at least a four-hour emergency power system test every three years. Written emergency plans must define responsibilities, staffing, backup personnel, and training.

On the lighting side, Van Meter and other emergency lighting best-practice resources describe the trade-offs between distributed battery units and centralized emergency lighting UPS systems. Distributed units, the familiar ŌĆ£bug-eyeŌĆØ fixtures, are cheap and easy to install but disperse testing and maintenance tasks across dozens or hundreds of points. A centralized UPS can simplify testing and circuiting but demands careful design of wiring and switching.

For sensors and actuators, the choice is similar. Some will have local battery backup or energy storage, especially in IoT and wireless deployments. Others will rely on emergency power feeders. Guidance from UpKeep and Intuz underscores that sensor and actuator systems in modern plants should be integrated into networked control and maintenance systems, with clear feedback of status, alarms, and test results.

From an emergency deployment standpoint, you want field devices that can be quickly bound into your existing control and communication schemes, not bespoke one-off fixes. That means favoring devices compatible with your current protocols and power standards and ensuring your CMMS is ready to capture test and maintenance data as soon as a device is commissioned.

In practice, when I am asked to deploy or replace an emergency sensor or actuator in a hurry, my mental workflow looks something like the table below. It is not a substitute for codes, but it keeps the important questions in front of you when time is short.

| Step or Aspect | What You Ask Yourself | Example Guidance to Lean On |

|---|---|---|

| Safety and stabilization | Is the area safe to enter and work in, and are electrical hazards controlled? | Electrical emergency response best practices that stress calm assessment and safe deŌĆæenergizing |

| Hazard and environment | What can burn, leak, or fail here, and how dirty, hot, or windy is it? | OSHA fire detector selection guidance and Venus Automation notes on harsh environments |

| Device type and function | Do I need smoke, heat, flame, vibration, position, or flow detection, and what action must follow? | OSHA smoke, heat, and flame detector roles; Renke vibration sensor context; UpKeep sensor roles |

| Actuator characteristics | What fail-safe position, torque, speed, duty cycle, and hazard rating do I need? | Indelac pneumatic versus electric actuator selection and Venus Automation safety switches |

| Certification and labeling | Does this device and every accessory carry the right zone, class, and safety markings? | Intrinsically safe deployment checklist stressing certification and label integrity |

| Power and visibility | What power source keeps this device alive and visible for at least ninety minutes? | NFPA 101 emergency lighting rules and NFPA 110 generator and transfer switch requirements |

| Installation quality | Is it mounted, protected, and spaced according to manufacturer and code guidance? | OSHA detector mounting and spacing rules and Koorsen emergency lighting installation notes |

| Testing and documentation | Have I functionally tested it and logged what I did, including next test dates? | NFPA 101 monthly and annual test requirements, Zapium and Yadkin maintenance checklist practices |

If you can answer those questions under pressure, you are already ahead of the pack.

From a safety and compliance standpoint, bypassing a safety sensor is extremely risky. OSHA fire detection requirements and NFPA life-safety codes assume that detection, indication, and actuation devices are present and functional. Removing or bypassing them not only increases life-safety risk but can also put you out of compliance and create liability exposure. In true emergencies, your priority should be to shut down affected equipment and deploy a compliant replacement or engineered temporary safeguard, not to defeat a safety function.

The right answer depends on your risk profile, but guidance from emergency lighting maintenance practice and intrinsically safe deployment suggests that you should at least stock the devices whose failure would force you to shut down critical processes or violate life-safety codes. That normally includes common fire detectors, emergency exit and egress lighting parts, critical safety switches, actuators on life-safety valves or dampers, and intrinsically safe devices in hazardous areas. The key is to combine a risk assessment with realistic procurement lead times so that a single failure does not leave you waiting days for a shipment.

Codes such as NFPA 101 and NFPA 110 expect qualified professionals to design, install, and maintain life-safety systems, and OSHA requires compliance with recognized engineering practices. In many facilities, that means engineering, maintenance, and safety or fire protection representatives jointly approving any change to emergency sensors, actuators, or power systems, with documentation kept for inspection by the authority having jurisdiction.

In the field, the moment of truth does not wait for you to finish a spec sheet. When a detector fails, a generator stumbles, or an actuator refuses to move during an emergency, the only thing that matters is whether you can put the right device in the right place, on the right power source, tested and documented, before the next incident hits. If you build your emergency sensor and actuator supply around the same rigor that NFPA, OSHA, and emergency lighting experts use for life-safety systems, rapid deployment stops being a scramble and becomes just another part of doing the job right.

Leave Your Comment