-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for ŌĆ£ŌĆØ.

When a Turck sensor appears dead on a machine, production stops and the pressure on the controls engineer spikes immediately. On paper, a proximity or analog sensor is simple: it turns on when a part is present or sends a clean 4ŌĆō20 mA signal. In the field, the reality is messier. Power supplies sag, PNP/NPN wiring gets crossed, and I/O blocks quietly sit in fault mode while everyone blames the sensor.

In this article I will walk through how I troubleshoot ŌĆ£no output signalŌĆØ issues with Turck sensors on real factory floors. I will lean on TurckŌĆÖs own explanations of how their inductive sensors work, community experience around Turck analog I/O blocks, and the practical wiring and software habits that consistently fix these problems in the field.

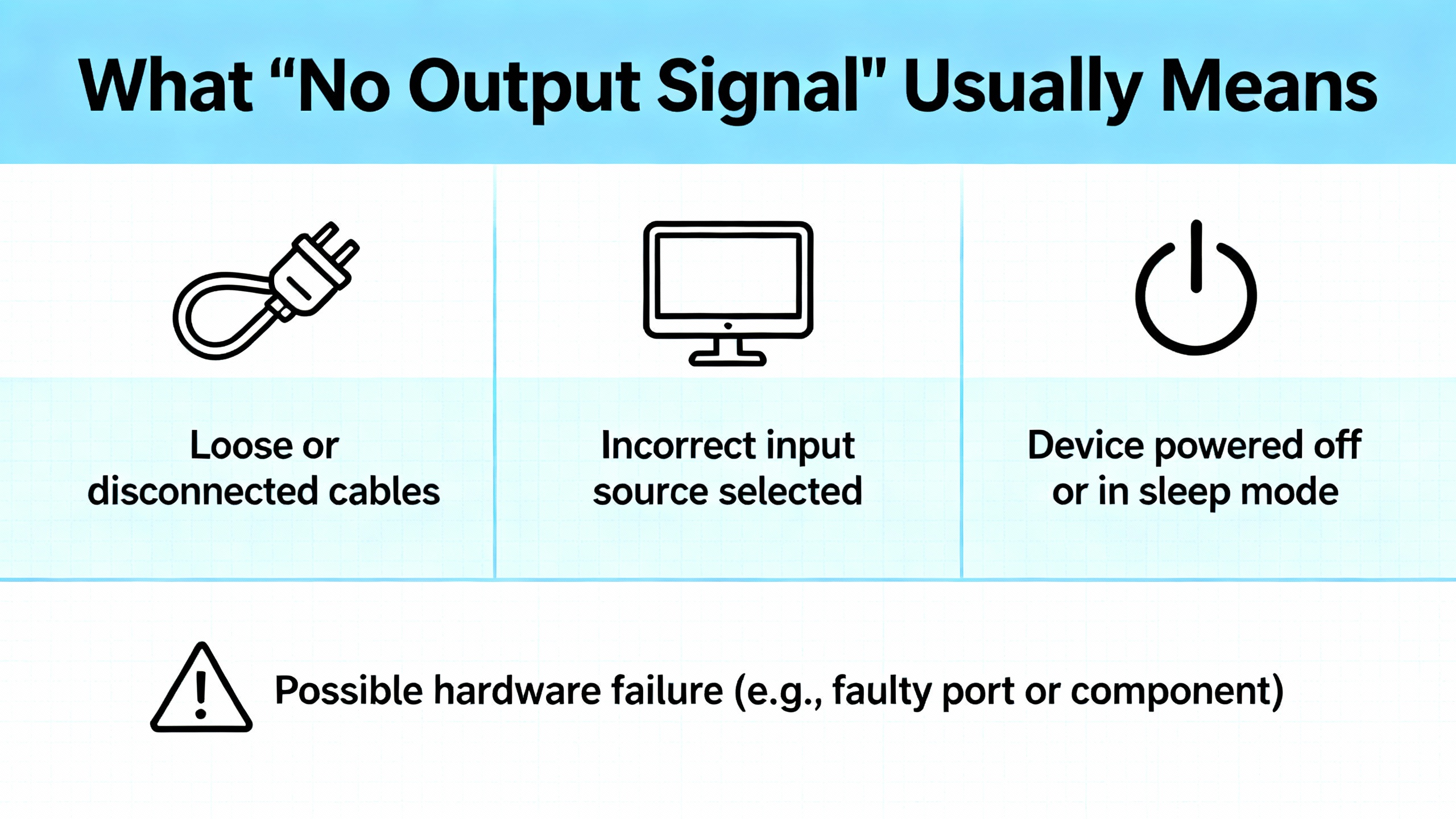

When technicians say a Turck sensor has ŌĆ£no output,ŌĆØ they often mean one of several different things, and it is important to clarify this before you start digging into the system.

Sometimes the PLC input never changes state, so the sensor seems permanently off. In other cases an analog channel is pinned at zero or at some fault value, even though the process is clearly moving. I also see cases where the sensorŌĆÖs own LED switches reliably, but neither the PLC nor a microcontroller (like an Arduino) reads any change. Finally, you occasionally encounter a true sensor failure, where the device neither powers up nor drives any output regardless of conditions.

Distinguishing between ŌĆ£no output at the sensorŌĆØ and ŌĆ£no signal seen by the controllerŌĆØ is the first critical step. The troubleshooting approach for a dead sensor is very different from the approach for a configuration mismatch, especially when Turck I/O blocks and higher-level software such as Codesys are involved.

TurckŌĆÖs own explanations of inductive proximity sensors describe a straightforward chain: a coil with a ferrite core, a highŌĆæfrequency oscillator, a detector circuit, and a solidŌĆæstate output stage. The coil and core project an electromagnetic field out of the sensing face. When a metal target enters this field, eddy currents are induced on the surface of the metal. Those eddy currents absorb energy from the oscillator, which reduces the oscillatorŌĆÖs amplitude. The detector circuit monitors that amplitude and flips the output when the change crosses a defined threshold. When the metal moves away, the oscillator recovers and the output switches back.

This internal model explains several typical failure symptoms. If the oscillator never starts because there is no supply voltage or because internal electronics are damaged, the detector never sees a valid signal and the output will not switch. If the detector is working but the solidŌĆæstate output stage is miswired or shorted into the load, the sensorŌĆÖs internal LED may change state while the external signal stays flat. If the target is not sufficiently metallic, or it is too far away, the eddy currents are weak and the device will behave like it has no output even though it is functioning exactly as designed. Keeping this physical picture in mind helps you avoid chasing ghosts in PLC code when the real issue is that the sensor field never changes.

On every ŌĆ£no outputŌĆØ call I start with supply and reference, long before touching ladder logic or input card settings. Turck manuals for discrete sensors typically specify a nominal DC supply, often somewhere in the neighborhood of 10ŌĆō30 VDC, with 24 VDC common in industrial panels. If the sensor does not see clean voltage between its supply and reference, nothing downstream will work.

In practice I measure directly at the sensor connector between the supply lead and the reference or common lead. If the reading is marginal or disappears under load, the problem is not the sensor; it is the wiring, a loose terminal, a dead fused branch, or shared common problems. On mixed systems where Turck devices share power with drives, solenoids, and other inductive loads, you must also watch for ground reference issues. If the PLC input module and sensor do not share a stable reference, the sensor can be switching perfectly while the input never crosses its detection threshold.

On analog current loops that feed Turck TBEN blocks or similar I/O modules, the same rule applies. The loop needs a stable DC source and a complete loop through the sensor, wiring, and input channel. Any open connection in that loop will yield what looks like ŌĆ£no outputŌĆØ but is actually ŌĆ£no current path.ŌĆØ

Turck USA highlights PNP and NPN confusion as one of the most common reasons sensors do not behave in the field, and my experience matches that exactly. In a PNP configuration, the sensor sources current into the load when it turns on. In an NPN configuration, the sensor sinks current to reference when it turns on. Many PLC input cards are designed primarily for PNP sensors, and wiring an NPN sensor into a sourcing input without proper reference and pull-up will result in no detectable change.

A quick way to visualize the difference is to think about where the switching transistor sits relative to the load. A PNP output sits above the load and connects it to positive when active. An NPN output sits below the load and connects it to reference when active. If your sensor and input module disagree about who is sourcing and who is sinking, you can have a perfectly working sensor driving a perfectly good input card and still see nothing change on the PLC.

The following table summarizes the core behaviors that matter during troubleshooting.

| Output type | Current direction when ON | Common PLC input pairing | Typical field symptom when mismatched |

|---|---|---|---|

| PNP (sourcing) | From sensor to input or load, toward reference | Sinking inputs | Sensor LED changes but PLC bit never turns on, input sits low |

| NPN (sinking) | From supply, through load, into sensor to reference | Sourcing inputs | Input may float or stay high; no clean state change detected |

When I encounter a ŌĆ£deadŌĆØ Turck proximity sensor that has a switching LED, my next step is to confirm the output type against the input card documentation. If the types do not match, the fix is usually just a wiring change, a different card type, or choosing the correct sensor variant rather than replacing the device.

Turck literature on sensor electrical characteristics emphasizes that output behavior depends not only on PNP vs NPN but also on whether the sensor is wired as a twoŌĆæwire or threeŌĆæwire device. ThreeŌĆæwire sensors (with supply, reference, and output) tend to behave more predictably with PLC inputs, because the load sees a clean switch referenced to a common supply.

TwoŌĆæwire sensors, by contrast, place the electronics and the load in series. Some current must flow even when the device is ŌĆ£offŌĆØ to power the internal circuits, and the voltage across the load in the off state may not drop all the way to zero. If the PLC input requires a deeper voltage drop to register an off condition, the input may appear to be stuck, or it may never rise high enough to register on. When someone later swaps a threeŌĆæwire Turck sensor into a circuit designed for a twoŌĆæwire device, or vice versa, the result often looks like a dead sensor even though the problem is the load and the input characteristics.

When faced with no output on a twoŌĆæwire Turck sensor, I measure both current and voltage across the input terminals with and without the target present. If the device is drawing some current but the voltage change is too small to cross the input thresholds, the solution is to adjust the load, add a dedicated input module designed for twoŌĆæwire sensors, or select a sensor with electrical characteristics that match the existing input hardware.

Many Turck proximity sensors include an LED at the sensing head. This LED is extremely valuable for separating field wiring issues from deviceŌĆælevel failures. If the LED never lights under any condition, that almost always means one of three things: there is no supply power at the device, the internal electronics are damaged, or the target does not meaningfully affect the sensorŌĆÖs field. If the LED behaves as expected when a metal target approaches but the controller reads nothing, the problem is upstream of the sensor: wiring from the sensor back to the control cabinet, mismatched I/O types, or input module settings.

Turck manuals for various products also note internal protective features such as shortŌĆæcircuit and overload protection. In real installations I occasionally see cases where a wiring error creates a brief short, the protection trips, and the sensor appears to lose its output. Power cycling the device after correcting the wiring can restore normal operation, so it is worth including a controlled power reset in your troubleshooting routine once the wiring is confirmed.

Community discussions around Turck proximity sensors connected to Arduino boards reinforce that wrong readings or ŌĆ£no signalŌĆØ are not just hardware problems. Moderators consistently insist on seeing both the full sketch and a clear, schematicŌĆæstyle wiring diagram before offering advice. That insistence is justified. When a Turck sensor feeds a microcontroller input, the codeŌĆÖs pin configuration, internal pullŌĆæups or pullŌĆædowns, and timing all influence whether an apparently healthy sensor shows up in software.

For example, configuring an input pin incorrectly, sampling too quickly without debounce, or forgetting to share a common reference between the sensor and the board will all present as ŌĆ£no outputŌĆØ to someone watching the serial monitor. The hardware may be fine; the microcontroller simply never sees the transitions. In industrial control environments, the same principle applies: ladder logic, input filter settings, and scaling can mask or distort a perfectly good signal. That is why I always verify the sensor and the raw input status in diagnostic views before concluding anything about the device.

For analog signals, the most instructive case comes from the Turck TBENŌĆæS2ŌĆæ4AI block used with Codesys. Users reported that when they configured a channel for 4ŌĆō20 mA input, the moduleŌĆÖs LED turned red and indicated a fault. Changing the configuration to 0ŌĆō20 mA made the fault disappear, and the LED turned green. That behavior pointed to a configuration or scaling problem rather than a wiring failure.

Key lessons came out of that discussion. First, the TBEN block has its own internal configuration, accessible via its web interface. Codesys settings do not necessarily overwrite the blockŌĆÖs channel mode. Therefore, it is not enough to set ŌĆ£4ŌĆō20 mA inputŌĆØ in the PLC project. You must log into the TBEN moduleŌĆÖs web page, navigate to the specific port, and confirm that the channel is set to current input with the correct range. Users mentioned logging in through the moduleŌĆÖs IP address using an administrative account to check live measured values directly on the block.

Second, the TBENŌĆæS2ŌĆæ4AI converts the analog current to a 16ŌĆæbit digital value. The PLC program must then scale this raw number into engineering units. If that scaling is wrong, Codesys may show values that appear out of range, even though the TBEN hardware is measuring the loop correctly. Misconfigured data types, mismatched ranges (0ŌĆō20 mA versus 4ŌĆō20 mA), and inconsistent offset handling can all produce what looks like ŌĆ£no outputŌĆØ or a red error indicator for a loop that is electrically sound.

Finally, the discussion reinforced basic analog troubleshooting steps that hold across vendors. You confirm current on the loop with a meter, doubleŌĆæcheck wiring from the sensor to the TBEN block, verify you are using the intended channel, and test with a knownŌĆægood sensor or simulator if necessary. Restarting the Codesys runtime or power cycling the system after making configuration changes can clear stale configuration states between controller and I/O block.

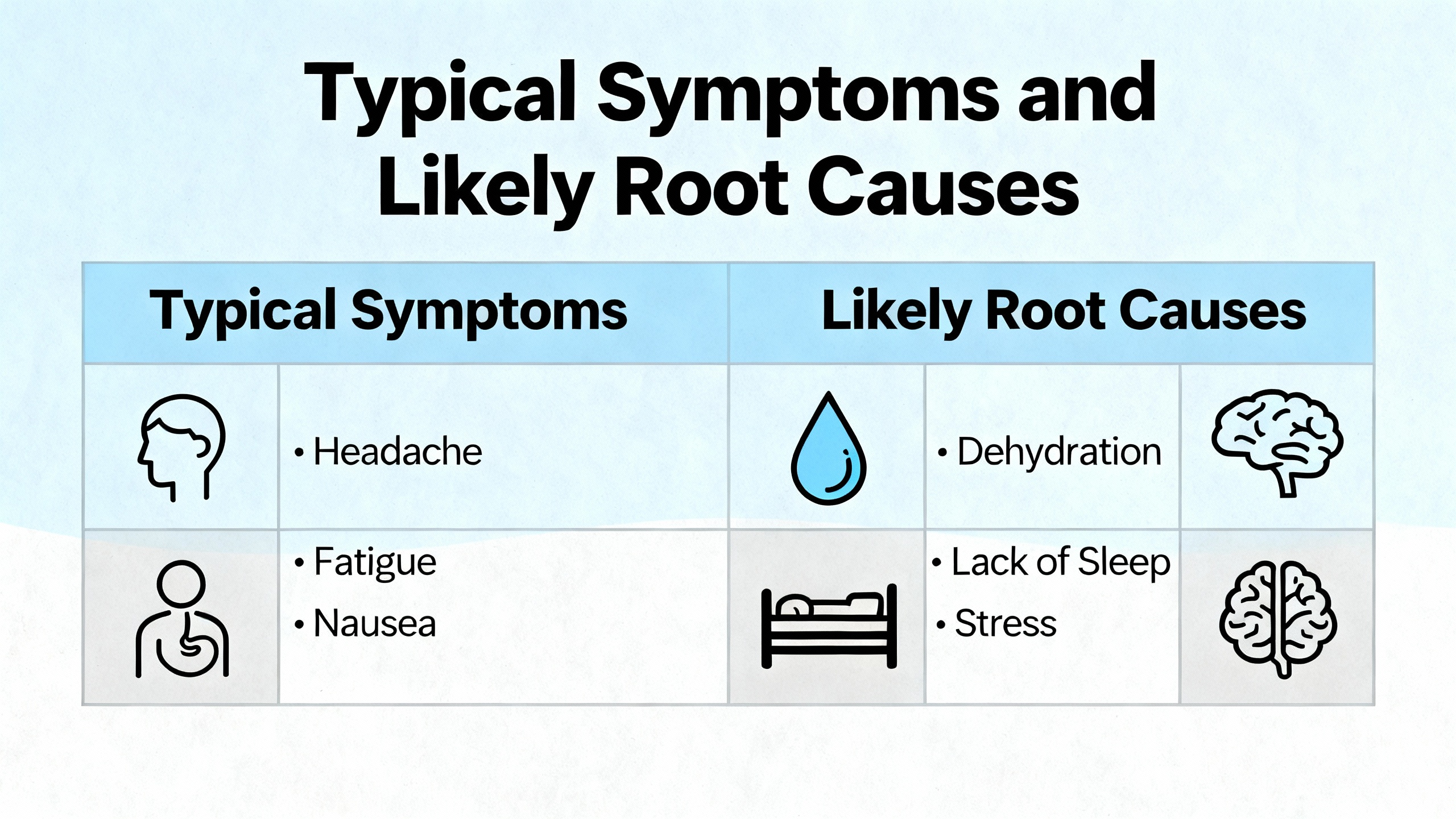

With enough field calls, patterns emerge. I find it useful to think in terms of symptom clusters rather than isolated failures. The table below summarizes several common ŌĆ£no outputŌĆØ situations with Turck sensors and associated hardware, along with the most probable causes and the checks that typically confirm them.

| Symptom at controller | Likely root cause | Practical check |

|---|---|---|

| Discrete input never turns on, sensor LED switches visibly | PNP/NPN mismatch, wrong input type, or incorrect wiring to PLC input terminal | Measure voltage at input relative to PLC common with target present and absent; compare behavior to input card specifications |

| Discrete input and sensor LED both dead | No supply voltage, open circuit, or sensor damage | Measure DC voltage at sensor supply pins; verify continuity of cable; substitute a knownŌĆægood sensor on same cable |

| Analog input shows 0 or fault, TBEN channel LED red | TBEN channel configured for wrong range or mode, or PLC scaling expects different range | Inspect TBEN web interface for channel mode and raw value; align Codesys scaling with block configuration; adjust to 4ŌĆō20 mA if loop is live at minimum current |

| Analog input fixed at one raw value, no visible noise | Loop open, sensor not driving, or channel forced | Measure loop current with meter in series; check for open wiring; verify that channel is not forced or overridden in software tools |

| Microcontroller or soft PLC sees flat value, but Turck sensor LED and wiring test good | Software configuration, pin mode, or scaling issue | Review code or PLC configuration; confirm pin mode, input filters, and scaling; monitor raw input register rather than processed tags |

Using a structured table like this during troubleshooting helps you avoid random changes. Instead you move from symptom to most probable cause, then to a specific field check that confirms or refutes that hypothesis.

On a real production line, I do not have the luxury of swapping parts blindly. My workflow for a Turck sensor with no apparent output is systematic and repeatable.

I start at the sensor itself. I check the LED while presenting a known metal target at known distances. If there is no LED or it never changes, I measure the supply voltage directly at the device and verify the presence of a stable DC source in the expected range. On analog loops, I measure current with a meter in series. If power and loop current are correct but there is still no LED change, it is reasonable to suspect a failed sensor or a target that simply does not interact with an inductive field.

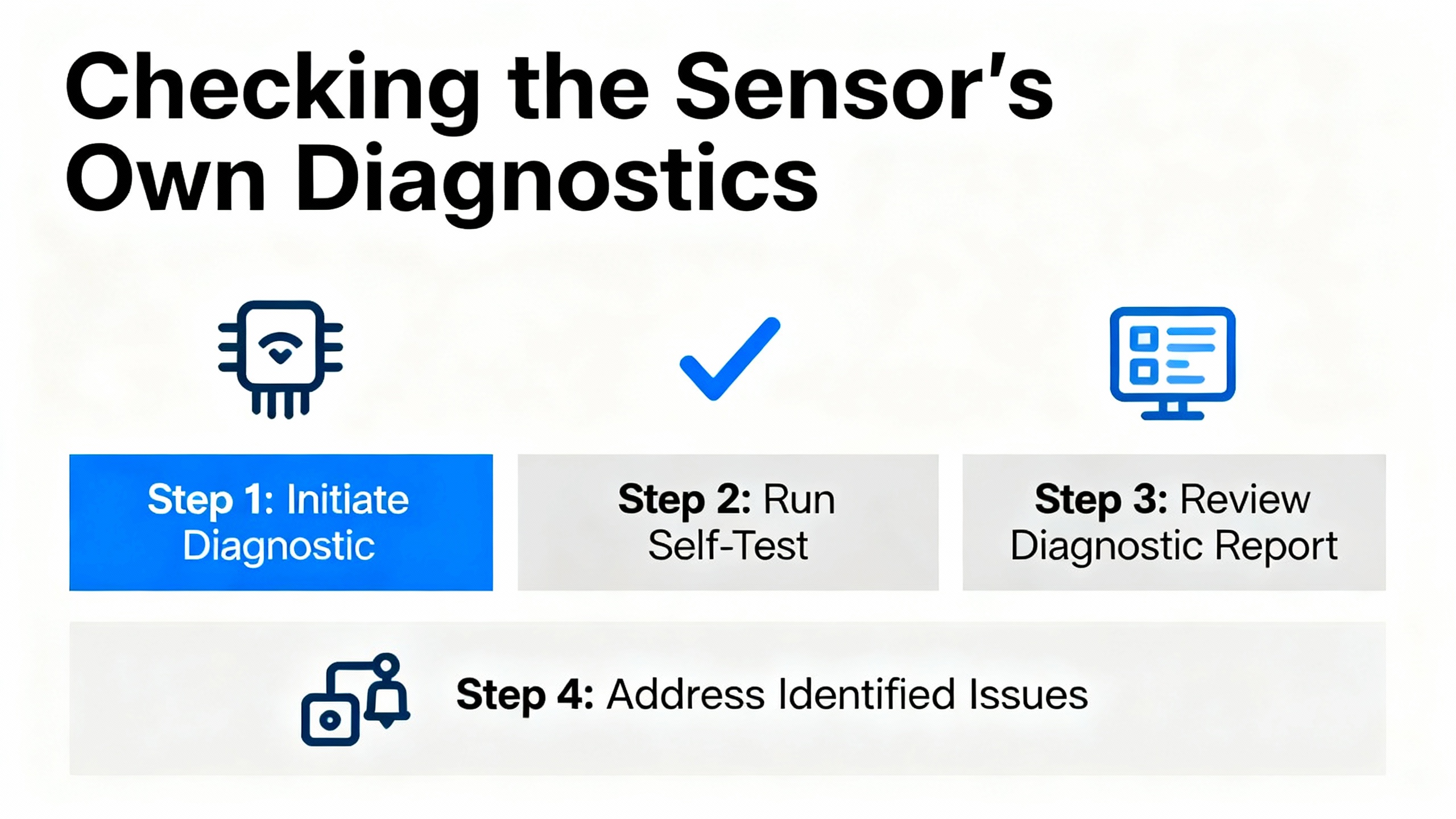

Once the sensor passes the basic checks, I follow the cable back to the I/O device. I confirm continuity and correct pin assignments, matching TurckŌĆÖs color codes and connector pinouts to the PLC or block terminals. If a Turck TBEN or similar Ethernet I/O block is in use, I log into its web diagnostics and check the channel mode, raw values, and any diagnostic flags. Seeing a live raw value on the block but nothing in the PLC indicates a software or communication issue, not a hardware one.

Only after the hardware and I/O diagnostics look solid do I move into the controller program. I observe the raw input bits or words, not just downstream tags that might be filtered or conditioned. I add temporary rungs or debug prints if necessary to capture state changes. For Codesys systems working with 16ŌĆæbit analog values, I confirm that scaling instructions use the correct low and high engineering ranges for the 4ŌĆō20 mA span.

Throughout this process, I change only one thing at a time and reŌĆætest. That discipline prevents me from compounding issues and makes it much easier to roll back when a supposed ŌĆ£fixŌĆØ actually makes the problem worse.

Most ŌĆ£dead sensorŌĆØ calls are preventable with good design and documentation. TurckŌĆÖs guidance on sensor selection, as well as standard controls engineering practice, points to several habits that pay off long term.

The first habit is to match sensor output type and input hardware at the design stage, not during commissioning. When you specify a Turck PNP sensor, pair it with sinking inputs in the PLC or I/O block. When NPN is required for legacy reasons, document that pairing clearly. The same is true for analog ranges: if your process measurement uses a Turck device with a 4ŌĆō20 mA output, configure both the I/O module channel and the scaling block in the PLC consistently. Randomly mixing 0ŌĆō20 mA and 4ŌĆō20 mA configurations is a recipe for red fault LEDs and flatlined readings.

The second habit is to insist on clear, schematicŌĆæstyle wiring diagrams. Community moderators dealing with Turck sensors on development boards often refuse to troubleshoot without them, and they are right to do so. Schematic diagrams reveal shared commons, shield terminations, and connector pinouts in a way that breadboardŌĆæstyle pictures never do. In industrial panels, that level of clarity lets you hand the drawing to a technician and have them isolate wiring errors without guessing.

A third habit is to provide test points and diagnostic labeling in the panel. If you include labeled terminals for sensor supplies, common references, and analog loop measurements, technicians can quickly verify whether a Turck device is receiving power and driving current. Combined with the sensorŌĆÖs own LED and any I/O block web diagnostics, this gives a complete chain of observable points from device to PLC tag.

Finally, designing with the environment in mind reduces mysterious failures. Turck sensors are built for industrial use, but they still have specified operating temperature ranges, maximum switching frequencies, and protection ratings. Mounting a sensor where its cable is constantly flexed, or routing its cable in parallel with highŌĆænoise motor leads, may not cause immediate failures but will almost certainly lead to intermittent or total loss of output over time. Even when the documentation is not in front of you, respecting general guidelines for mechanical strain relief, shielding, and separation of signal and power wiring pays off.

Turck emphasizes that their support team is available at any phase of a project. In practice, I bring them in when I have exhausted the obvious field checks and I am still seeing unexplained behavior that appears deviceŌĆæ or configurationŌĆæspecific.

Examples include TBEN I/O blocks that show unexpected diagnostic codes even after configuration matches the documentation; advanced functions or protection modes that are not clearly described in the short manuals on hand; or edge cases where combining multiple features causes nonŌĆæintuitive interaction. In those cases a quick call or email to Turck support, with exact part numbers, firmware revisions, and screenshots of the web interface or PLC diagnostics, can save hours of trial and error.

The key is to approach support with the same discipline you apply on the plant floor. Document supply voltages, loop currents, wiring details, and software settings clearly. Having that information ready upfront allows TurckŌĆÖs engineers to move directly into meaningful analysis rather than spending the first conversation reconstructing your setup.

The fastest check is at the device. Present a known metal target to the sensing face and watch the builtŌĆæin LED if the sensor has one. If the LED switches while the target moves in and out of range, the sensor is detecting metal and driving its internal output. If the LED never lights, measure supply voltage at the device and confirm wiring. If you have supply but no LED response with a metal target at close range, the sensor is likely damaged or incorrectly specified for the target material.

Yes. TurckŌĆÖs own description of inductive proximity sensors makes clear that they detect metal targets by inducing eddy currents in the metal. NonŌĆæmetallic materials such as plastic, glass, or most liquids do not create the same energy loss in the oscillator, so the sensor will not switch. In that situation the device is functioning as designed, but from the controllerŌĆÖs perspective it appears to have no output. The remedy is to choose a sensing technology appropriate for the target, such as capacitive sensors, photoelectric sensors, or other types depending on the application.

If the analog signal runs through a Turck TBENŌĆæS2ŌĆæ4AI or similar block, a zero reading with a fault indicator often points to a configuration mismatch. The channel may be set for voltage instead of current, or for a 0ŌĆō20 mA range while the sensor is designed for 4ŌĆō20 mA. In the TBEN case, you must verify both the internal web configuration of the channel and the PLC programŌĆÖs scaling. Only when the block is configured correctly and sees actual loop current will the 16ŌĆæbit value it reports scale into a meaningful engineering number.

A Turck sensor that appears dead is rarely a mystery if you approach it methodically. Understand how the device is supposed to work, verify power and wiring at the sensor first, confirm that I/O hardware and software agree on ranges and types, and only then suspect the device itself. That is the mindset I carry onto every factory floor, and it is the difference between chasing ghosts for hours and having the line running again before the next break.

Leave Your Comment