-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for ŌĆ£ŌĆØ.

Keeping a line running is often won or lost in small details, and a ŌĆ£BATŌĆØ or ŌĆ£BATTŌĆØ light on an AllenŌĆæBradley controller is one of those details that deserves immediate attention. In the field, IŌĆÖve seen perfectly healthy machines go dark after a brief power dip simply because a backup cell had quietly aged out months earlier. This guide explains what that warning means, how to replace the battery without losing your program, and how to reset the controller to a clean bill of health. The focus is practical: what to do, why it matters, and how to avoid repeat visits. I reference reputable sources along the way, including Rockwell Automation literature, BatteryGuy Knowledge Base, AutomationForum, ACS Industrial, and HESCOŌĆÖs Rockwell troubleshooting guidance.

In AllenŌĆæBradley PLCs and PACs, the backup battery preserves volatile memory and the realŌĆætime clock when primary power is unavailable. That can include user logic, configuration, retentive data, and timekeeping depending on the platform and configuration. The batteryŌĆÖs job is simple: bridge short power losses and extended maintenance shutdowns so you resume where you left off. Many controllers use lithium cellsŌĆöoften lithiumŌĆæthionyl chlorideŌĆöat nominal 3.0 V or 3.6 V. Some designs add capacitorŌĆæbased energy storage for short retention windows. The exact behavior is modelŌĆæspecific, so it is essential to confirm in the product manual whether your controller stores the application in nonŌĆævolatile memory or relies on batteryŌĆæbacked RAM for the program, tags, or both. HESCOŌĆÖs Rockwell PLC troubleshooting notes and Rockwell Automation literature emphasize verifying how your controller saves program data and what the battery actually protects.

The practical implication is straightforward. A PLC may run normally with a depleted battery while it has power, but if mains power drops, you risk losing volatile contents. That is why maintenance teams should treat a battery warning as a live issue and avoid powering down until a backup and a plan are in place.

Plants typically encounter two backup approaches: capacitor assemblies for short retention and lithium cells for longer periods. Capacitor modules can hold up for brief outagesŌĆömeasured in days for some platforms and conditionsŌĆöwhile lithium cells deliver multiŌĆæyear retention under normal operating temperatures. AutomationForum notes that lithium assemblies typically last about two to five years, whereas capacitor assemblies are better suited to short durations measured around a few days. LithiumŌĆæthionyl chloride chemistries dominate PLC applications thanks to long shelf life and stable voltage profiles. Temperature, frequent powerŌĆæoffs, and controller age shorten service life, so a hot cabinet in August is not just an operator comfort issueŌĆöit directly affects how long your battery can be trusted.

| Backup method | Typical retention window | Typical chemistry/voltage | Where itŌĆÖs used | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capacitor energy storage | Hours to a few days | Not a primary ŌĆ£batteryŌĆØ chemistry | ShortŌĆæterm holdover | No cell to replace; simple | Not suitable for long offŌĆæperiods; life degrades with heat |

| Lithium battery assembly | Roughly 2ŌĆō5 years of service | LithiumŌĆæthionyl chloride, 3.0 V or 3.6 V | LongŌĆæterm retention | Long service life; stable voltage | Temperature and frequent cycling shorten life; requires scheduled replacement |

AllenŌĆæBradley controllers indicate low battery with a ŌĆ£BATŌĆØ or ŌĆ£BATTŌĆØ LED and often log a diagnostic message. Bastian Solutions describes a frontŌĆæpanel ŌĆ£BATŌĆØ indicator behavior where a steady red light points to a missing or nearly discharged battery. DOSupplyŌĆÖs technical overview notes that in some legacy PLCŌĆæ5 systems using 3.0 V cells, the warning threshold can be around 2.0 to 2.5 V and often implies roughly ten days of remaining retention. Treat any warning as a prompt to act immediately but methodically: back up the program, verify what memory is protected by the battery in your model, and plan the swap. ACS Industrial offers a critical caution from field experienceŌĆöif the red battery light is on, do not power down before you have a knownŌĆægood backup.

On many controllers with a frontŌĆæaccessible battery, BatteryGuyŌĆÖs guidance is to leave the PLC powered during the replacement to preserve memory. If the battery is buried behind a module that must be removed for access, disconnecting the power supply to avoid electric shock may be necessary; in that case, be prepared to reload the program afterward. The correct path depends on your controller family and how the battery is mounted, so follow the controllerŌĆÖs installation instructions and your facilityŌĆÖs electrical safety procedures.

Good preparation is what separates a routine change from a long night. Begin by uploading a full, knownŌĆægood backup of the controller program and relevant configuration. Pull retentive data and network settings if your software and controller allow. If your site manages dozens of Rockwell systems, HESCO recommends using AssetCentre to automate backups across the fleet; at minimum, maintain manual versioning and store your backups in more than one location.

Next, secure a matching replacement cell. AutomationForum and BatteryGuy both stress verifying voltage, chemistry, physical size, connector type, and OEM compatibility. Check the date code and avoid cells with questionable storage history. If a frontŌĆæaccessible battery is clearly hotŌĆæswappable per the manual, plan to keep the controller energized; if access requires removing modules or exposing energized conductors, plan a controlled powerŌĆædown, coordinate with operations, and bump that backup to the top of your checklist.

Finally, gather a digital multimeter and any hand tools. A DMM is valuable not only for testing the removed cell but also for confirming the installed cellŌĆÖs voltage if your controller allows access without compromising safety. Use DC volts range above the nominal battery rating; do not use AC for this test.

A reliable procedure follows a simple arc: prepare the controller, make the swap, and validate memory retention. In preparation, ensure the machine is in a verified safe state. If your model supports hotŌĆæswap and the battery is frontŌĆæaccessible, keep the PLC powered to preserve RAM; if it is not hotŌĆæswappable, execute a controlled stop and power down per your lockout plan. Confirm again that the backup file is current and available.

When ready to swap, open the battery compartment or remove the minimal hardware required to access the cell. Release the retaining clip if present, unplug the connector, and remove the battery carefully to avoid shorting the terminals. Handle the new cell by the edges and avoid contaminating contacts; PanasonicŌĆÖs handling guidance echoed in engineering forums warns that oily films can cause lowŌĆælevel discharge over time. Connect the new battery with correct polarity, place it under the retaining clip, and reseat any module or door. Minimize the time the controller is without battery support. If the controller was powered down for access, restore power only after youŌĆÖve closed the compartment and replaced any covers or modules fully.

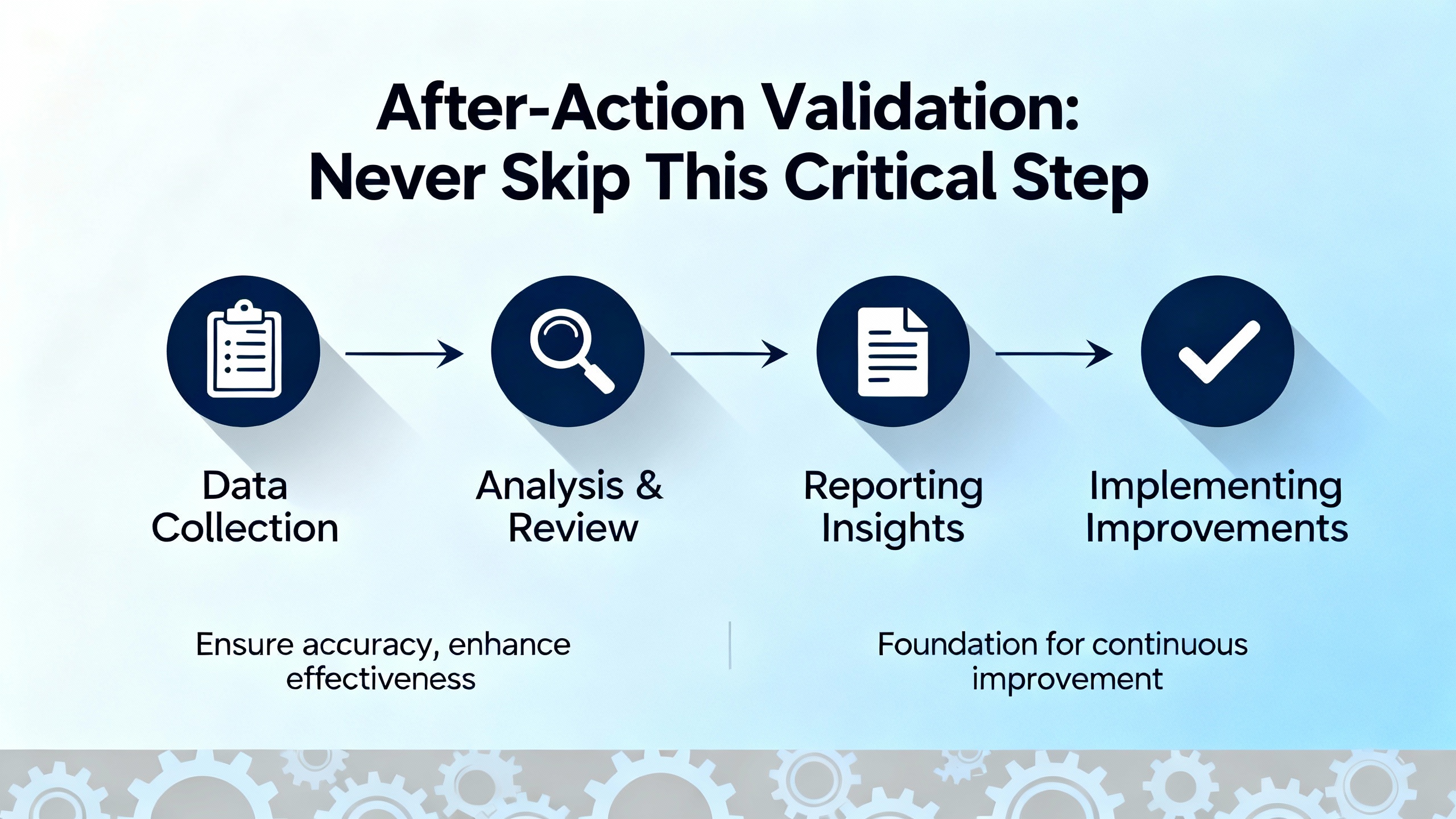

The validation phase is where many teams save themselves from a callback. Confirm that the ŌĆ£BAT/BATTŌĆØ indicator clears after installation. If a diagnostic bit remains latched, acknowledge it in your HMI or software, then check again. Many HMIs can display fault codes such as battery alerts; Bastian Solutions encourages mapping those diagnostics to the screen for quicker troubleshooting. Verify program integrity by going online with the controller and confirming that retentive tags look as expected. Reset and verify the realŌĆætime clock, then perform a planned power cycle if appropriate for your process to prove that memory retention is working and that the warning does not reappear. If the LED persists after a good swap, AutomationForum recommends testing the new cell with a multimeter and reŌĆæchecking probe connections before suspecting the controller.

Technicians often want hard numbers to decide whether a removed cell is genuinely spent. AutomationForum offers useful DMM guidance: test on a DC range above nominal, and compare to the table below. DOSupplyŌĆÖs overview aligns on thresholds and emphasizes using DC measurement to avoid misreads.

| Nominal cell | FullŌĆæhealthy reading | LowŌĆæwarning band | Replace now |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3.0 V lithium | At or above 3.0 V | About 2.0ŌĆō2.5 V | Below about 2.0 V |

| 3.6 V lithium | About 3.6ŌĆō3.7 V | About 2.4ŌĆō2.9 V | Below about 2.4 V |

These are atŌĆærest, noŌĆæload checks; a cell that sags under load is effectively worse. If you have persistent battery warnings with seemingly healthy cells, broaden the diagnosis beyond the battery.

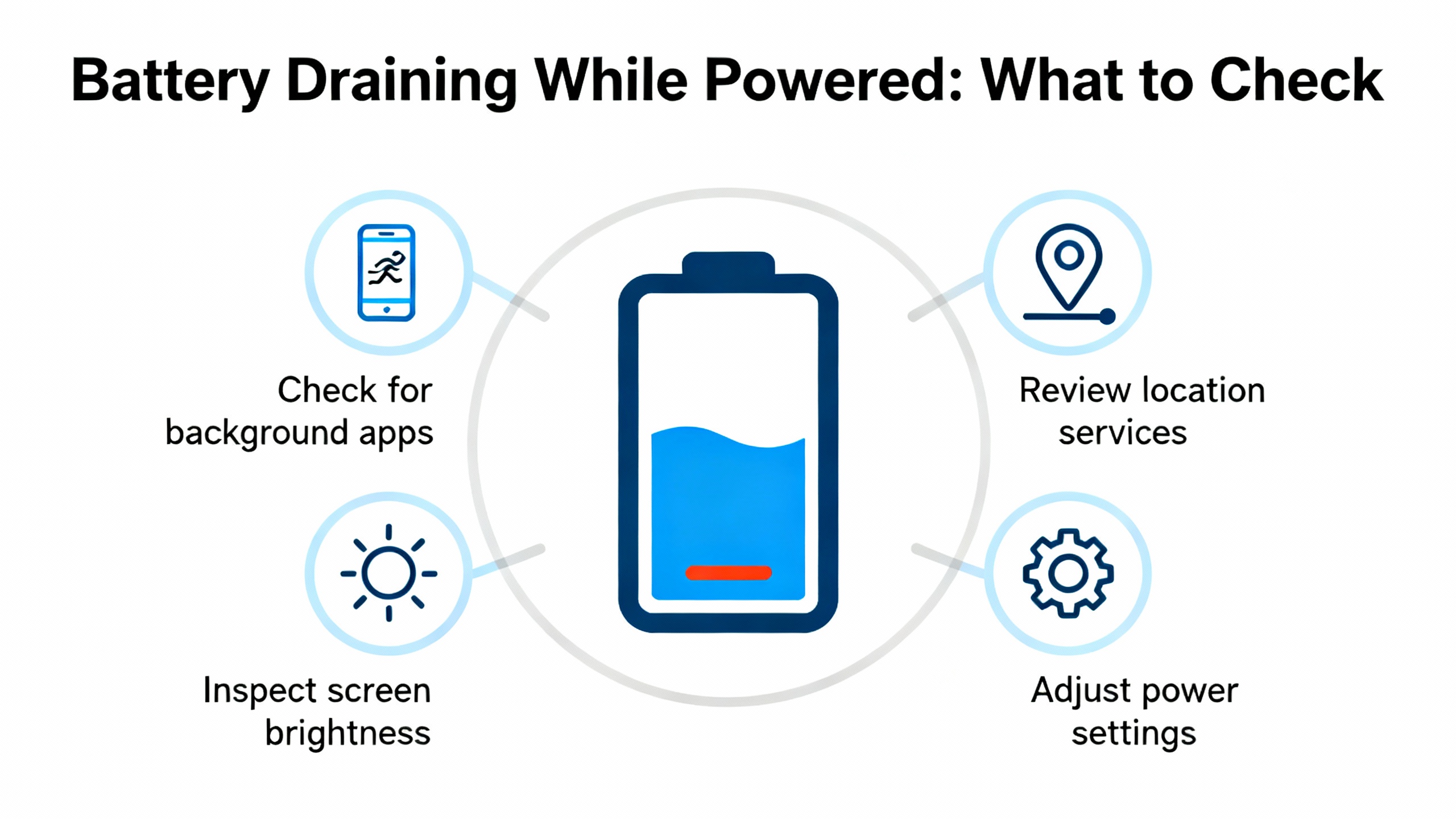

A less common but consequential scenario is a battery that keeps draining even with the PLC powered. An Automation & Control Engineering Forum discussion describes how, in some architectures, if the backplane or internal supply voltage falls below the battery voltage, current can backflow and the battery starts to support the memory even with mains present. The normal design uses diode isolation to prevent this. If a drain persists, investigate power supply health under load, reseat modules, and confirm that the rackŌĆÖs current draw is within specification; an overloaded supply can sag enough to cross this threshold. In multiŌĆærack systems, swapping power supplies between racks can help isolate whether the issue follows the supply or stays with the rack.

Resetting is less about pushing a ŌĆ£resetŌĆØ button and more about clearing the battery diagnostic, reŌĆæestablishing accurate timekeeping, and validating logic and data. After the swap, acknowledge batteryŌĆærelated messages in the controller and HMI as needed so that you are looking at current states rather than latched history. Set the realŌĆætime clock accurately; a bad RTC can cause headaches with scheduled sequences, data stamps, and batch records. Confirm that any batteryŌĆædependent retentive data has been preserved or, if your model uses nonŌĆævolatile storage for logic, verify that the saved application is intact. Finally, schedule a short, supervised power cycle. If the system restarts cleanly without battery diagnostics, you have confidence that the replacement and reset are complete.

Replacing a PLC battery should be a scheduled activity, not a firefight. BatteryGuy and Industrial Automation Co. both place typical service life at about two to five years and recommend proactive replacement every two to three years. Some OEM guidance for legacy families such as AllenŌĆæBradley SLC 500 and PLCŌĆæ5 is more conservativeŌĆöAutomationForum notes annual replacement when systems are frequently powerŌĆæcycledŌĆöand cautions against exceeding three years even in continuous service. Heat accelerates aging, so manage cabinet temperature, particularly in summer, and keep dust off heat sinks and filters. HESCO encourages routine visual checks, and, importantly, keeping automated backups current so a dead battery can never escalate into lost code.

If you manage a larger installed base, standardize a maintenance calendar and hold teams accountable for updating controller labels and CMMS records with battery replacement dates. An inexpensive label on the door and a traceable work order are worth more than another spare cell sitting on a shelf.

Battery selection is not a place for guesswork. Match the original voltage, chemistry, connector, and capacity; choose OEMŌĆæapproved part numbers when available to avoid subtle incompatibilities. Inspect date codes and avoid cells that have been stored improperly. Store spares in a cool, dry area in their original packaging and avoid extreme temperatures. Handle cells with clean, dry hands or gloves, and avoid shorting terminals with tools or jewelry. Engineering forum experience and Panasonic handling guidance highlight that residues on contacts can create continuous lowŌĆælevel discharge; keeping contacts clean and minimizing handling time preserves service life.

Disposal of lithium cells should follow facility and local rules. BatteryGuy advises that visibly damaged or leaking cells be placed in a polyethylene bag with about one ounce of calcium carbonate, then doubleŌĆæbagged and heatŌĆæsealed, and then routed through an appropriate disposal company. For intact spent cells, use your established hazardous waste stream.

Battery changes are deceptively simple tasks performed inside control panels that also contain dangerous energy. Follow your lockout/tagout procedures, particularly if access to the battery requires removing modules or exposing conductors. If your model explicitly allows hotŌĆæswap and the battery is frontŌĆæaccessible without exposure to energized parts, a powered swap can be the right choice to protect memory. If there is any doubt, plan a controlled stop. Keep one hand clear of grounded surfaces when reaching into panels to minimize fault current paths, use insulated tools, and coordinate with operations so you do not trigger unexpected trips midŌĆæproduction. The few minutes spent on a preŌĆæjob brief often save hours.

Operators often ask whether they should always change batteries with power on. The best answer is modelŌĆæspecific. BatteryGuy describes two realities: when a battery is accessible on the front of the processor, replacing with the PLC powered can preserve memory; when access requires removing modules, power should be disconnected to avoid shock, and you must be prepared to reprogram or restore from backup. Weigh the risks. A powered swap can protect volatile memory, but only when you can do it without exposing live conductors. A poweredŌĆædown swap removes shock hazards but requires absolute confidence in your backups and a clear recovery plan. In both cases, minimizing the time between removal and insertion matters because many controllers only have a small capacitor buffer.

When the cell is in and the warning has cleared, take a moment to verify what matters. Confirm that the HMI shows no lingering battery faults. Check that retentive tags and recipe data look correct. Reset the date and time and verify data stamps in a trial run. If feasible, perform a single controlled power cycle to confirm memory retention and a clean restart. Then record the replacement date on the controller and in your CMMS, update spare stock levels, and close the loop with a short note to the team about any anomalies. These small habits prevent repeat work and build trust with production.

When limits are fuzzy, technicians often overŌĆæ or underŌĆæservice. The thresholds above are a solid field guide. At the cell level, consider a 3.0 V lithium unhealthy below about 2.5 V and due for replacement below about 2.0 V, and a 3.6 V lithium unhealthy below about 2.9 V and replaceŌĆænow below about 2.4 V. Treat a battery warning as roughly days, not months, of safe retention remaining. For service intervals, the twoŌĆætoŌĆæthreeŌĆæyear cadence is a reasonable default; shorten that interval in hot, powerŌĆæcycled environments, and be particularly cautious with older SLC 500 and PLCŌĆæ5 hardware where manufacturer guidance has historically been conservative.

A battery light on an AllenŌĆæBradley controller is not a crisis if you respect what itŌĆÖs telling you. Back up first, know whether your model uses batteryŌĆæbacked RAM or nonŌĆævolatile storage for the application, and follow an accessŌĆæappropriate procedure to swap the cell. Confirm the warning clears, reset the clock, and verify that data and logic are intact. Adopt a twoŌĆætoŌĆæthreeŌĆæyear replacement cadence, tighten environmental controls that accelerate aging, and automate backups so a dead battery is an inconvenience rather than an outage. The teams that treat battery maintenance as a routine asset task spend less time scrambling and more time producing.

Field experience supported by BatteryGuy and AutomationForum puts typical service life around two to five years, with a proactive replacement cadence of two to three years. High temperatures, frequent power outages, and aging hardware shorten that timeline, while cool, stable cabinets help extend it.

If the battery is frontŌĆæaccessible and the manufacturer indicates hotŌĆæswap is supported, keeping the PLC powered preserves memory. BatteryGuy notes that when access requires removing modules, disconnecting power to avoid shock is the safer route, and you should be prepared to reload the program afterward. Always follow the modelŌĆæspecific manual.

It depends on the controller family and configuration. Some AllenŌĆæBradley controllers store the application in nonŌĆævolatile memory and use the battery mainly for the realŌĆætime clock and retentive data. Others rely on batteryŌĆæbacked RAM. HESCOŌĆÖs Rockwell guidance and Rockwell Automation literature both emphasize verifying how your controller saves program data and ensuring you have a current backup.

Start by confirming the new cellŌĆÖs voltage with a DMM on a DC range above nominal. AutomationForum recommends checking meter probes and connections, then reseating the connector. Clear latched alarms in the HMI or software, set the RTC, and powerŌĆæcycle if appropriate to confirm the warning does not reappear. Persistent warnings with a healthy cell warrant deeper power and backplane checks.

At rest, a 3.0 V lithium cell is healthy at or above 3.0 V, marginal around about 2.0 to 2.5 V, and ready for replacement below about 2.0 V. A 3.6 V lithium reads roughly 3.6 to 3.7 V when full, is marginal around about 2.4 to 2.9 V, and should be replaced below about 2.4 V. Measure on a DC range with a digital multimeter.

BatteryGuy advises placing the cell in a polyethylene bag with about one ounce of calcium carbonate, doubleŌĆæbagging, heatŌĆæsealing, and using a qualified battery disposal company. For intact spent cells, route them through your facilityŌĆÖs hazardous waste process and follow local regulations.

This guidance draws on Rockwell Automation literature, BatteryGuy Knowledge Base, AutomationForumŌĆÖs replacement procedure notes, ACS IndustrialŌĆÖs programŌĆæloss cautions, Bastian SolutionsŌĆÖ maintenance checkpoints, Industrial Automation Co.ŌĆÖs preventive maintenance practices, and HESCOŌĆÖs Rockwell PLC troubleshooting guidance. Each of these sources reinforces the same practical truths: replace on a schedule, back up before touching batteries, and validate after the swap.

Leave Your Comment