-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for ŌĆ£ŌĆØ.

When a plant manager tells me they want ŌĆ£alternatives to the Bently 3500/42M,ŌĆØ they usually mean two things at once. They want to benchmark Bently Nevada commercially, because purchasing requires multiple quotes, and they want to know whether a different platform could actually support modern predictive maintenance, not just trip the machine when it is already in trouble.

The reality is that the Bently Nevada 3500/42M is still a reference platform for highŌĆæend vibration protection. But the vibration monitoring market has shifted. According to MarketsandMarkets, vibration monitoring is projected to grow from about $1.85 billion in 2024 to roughly $2.69 billion by 2029, a compound growth rate around 7.8 percent, driven by predictive maintenance and wireless monitoring. That growth is not coming from one vendor. It is coming from a broad ecosystem of systems and sensors from companies such as Emerson, SKF, Metrix, National Instruments, Fluke, ifm, KCF Technologies, and several specialized wireless suppliers.

In this article, I will walk through how the 3500/42M fits into your architecture, what really needs to be replaced or complemented, and which alternatives make sense in practice if your goal is predictive maintenance rather than just likeŌĆæforŌĆælike rack replacement.

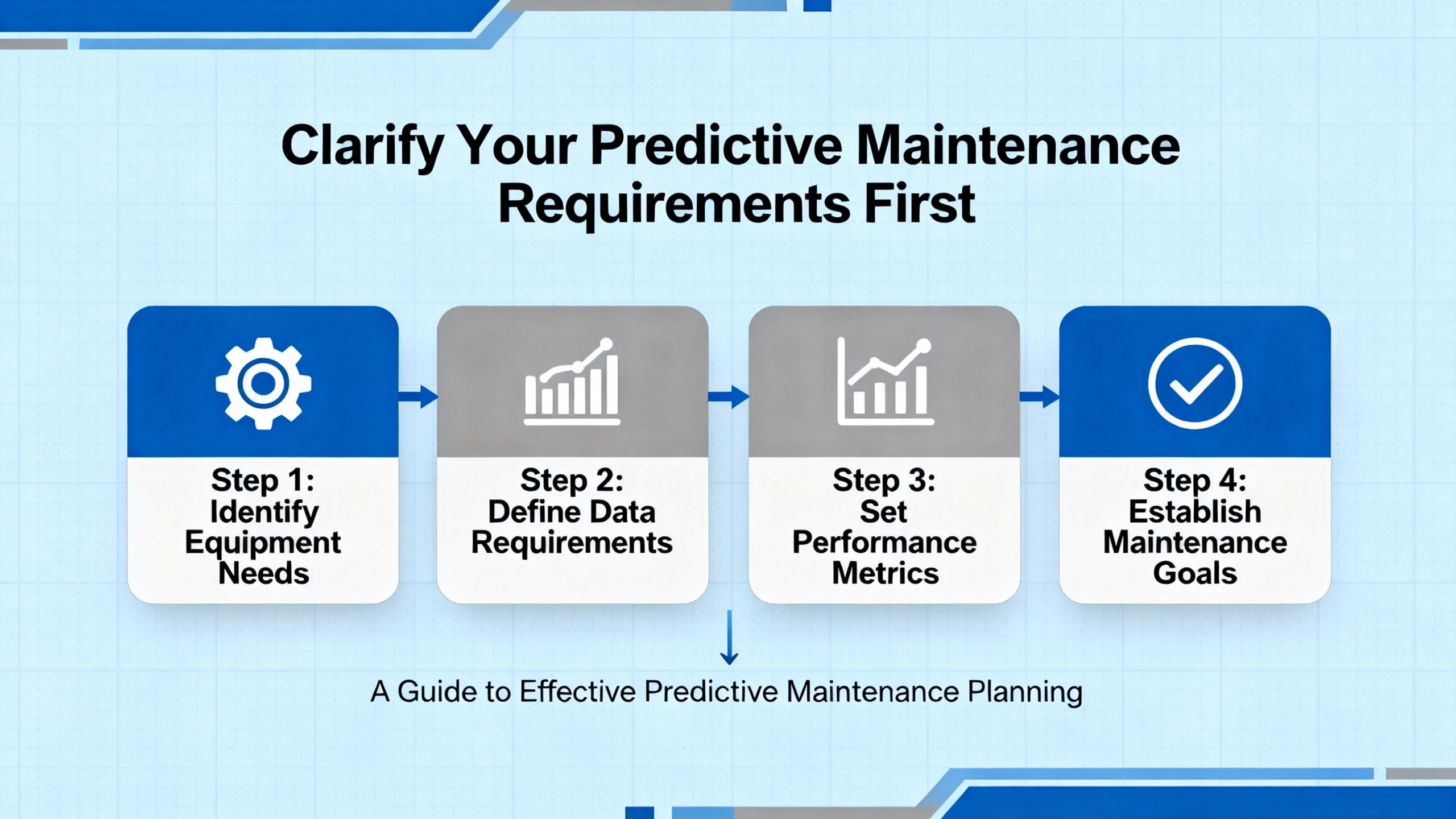

Before you can sensibly talk about alternatives, you need to be clear about the job your 3500 rack and 42M modules are doing today.

On critical turboŌĆæmachinery, such as generators, large compressors, and steam turbines, the standard architecture described in turbomachinery forums uses a set of permanent vibration sensors. These typically include proximity probes on shafts, velocity sensors, accelerometers on bearings, and a Keyphasor for phase reference. All of those signals land in a vibration rack that powers the sensors, performs realŌĆætime signal evaluation, and trips the machine if vibration crosses defined limits. That same rack usually provides buffered outputs on every channel so you can safely connect a data acquisition system, such as a Bently Nevada 408 feeding ADRE analysis software, without disturbing the protection circuitry.

In other words, the traditional Bently rack is first a machinery protection system and only second a data source for diagnostics. That sequence matters. A forum discussion on replacements comparable to the Bently 3500 underscores why reliability engineers treat Bently as the baseline option. They have decades of good experience with it and are understandably reluctant to ŌĆ£pay big bucksŌĆØ for something that is not yet ŌĆ£tried and true.ŌĆØ

From a predictive maintenance perspective, however, you really care about several capabilities that are not unique to Bently Nevada. You need sensors that capture the right frequencies and amplitudes for your failure modes. You need continuous or frequent data collection rather than just trip events. You need analytics that make it easy to diagnose misalignment, unbalance, looseness, and bearing faults. And you need clean integration into your control system, historian, and CMMS.

Those are the functions that alternative platforms have to deliver if they are going to replace or, more realistically, complement a 3500/42M.

I strongly recommend defining what you expect from your predictive maintenance program before you lock in any hardware. A reliability engineer on the SMRP Exchange, responsible for about twenty small chemical plants, put it well: with so many wireless vibration vendors and options, you need a clear minimum expectation for the program itself or you will not be able to compare solutions ŌĆ£apples to apples.ŌĆØ

For vibration, the sensing hardware has to cover the failure modes you care about. The SMRP discussion highlights the need for a sufficiently high maximum frequency, often around the 5 kHz range, and enough spectral resolution to separate bearing, gear, and structural frequencies. That is true whether you are reading proximity probes into a rack or wireless accelerometers into the cloud.

At the same time, even the best sensor is useless if you cannot deploy it at scale. Battery life, mechanical footprint, mounting style, and ease of installation matter. The SMRP engineer specifically calls out these points because they are trying to standardize across many small chemical facilities, which is a situation I see often in food, OEM, and midstream fleets.

On the software side, your vibration team expects the wireless platform to feel like their traditional routeŌĆæbased tool. That means access to rich time waveforms, spectra, and trends, not just trafficŌĆælight indicators. They also need configurable alerts, reusable analysis templates, and the ability to combine data with other condition monitoring technologies such as electrical signature analysis, oil analysis, infrared thermography, and process data from your DCS or SCADA.

Finally, predictive maintenance is not just about sensors and dashboards. The SMRP discussion stresses the value of integrating the vibration platform with the CMMS so that work requests and maintenance history can be viewed through one pane of glass. InstrumartŌĆÖs overview of vibration monitoring echoes this, pointing out that vibration is a core technique in life cycle asset management and is most powerful when it drives conditionŌĆæbased work rather than isolated reports.

Once those requirements are written down, you can reasonably judge which alternatives to the 3500/42M are realistic for your site.

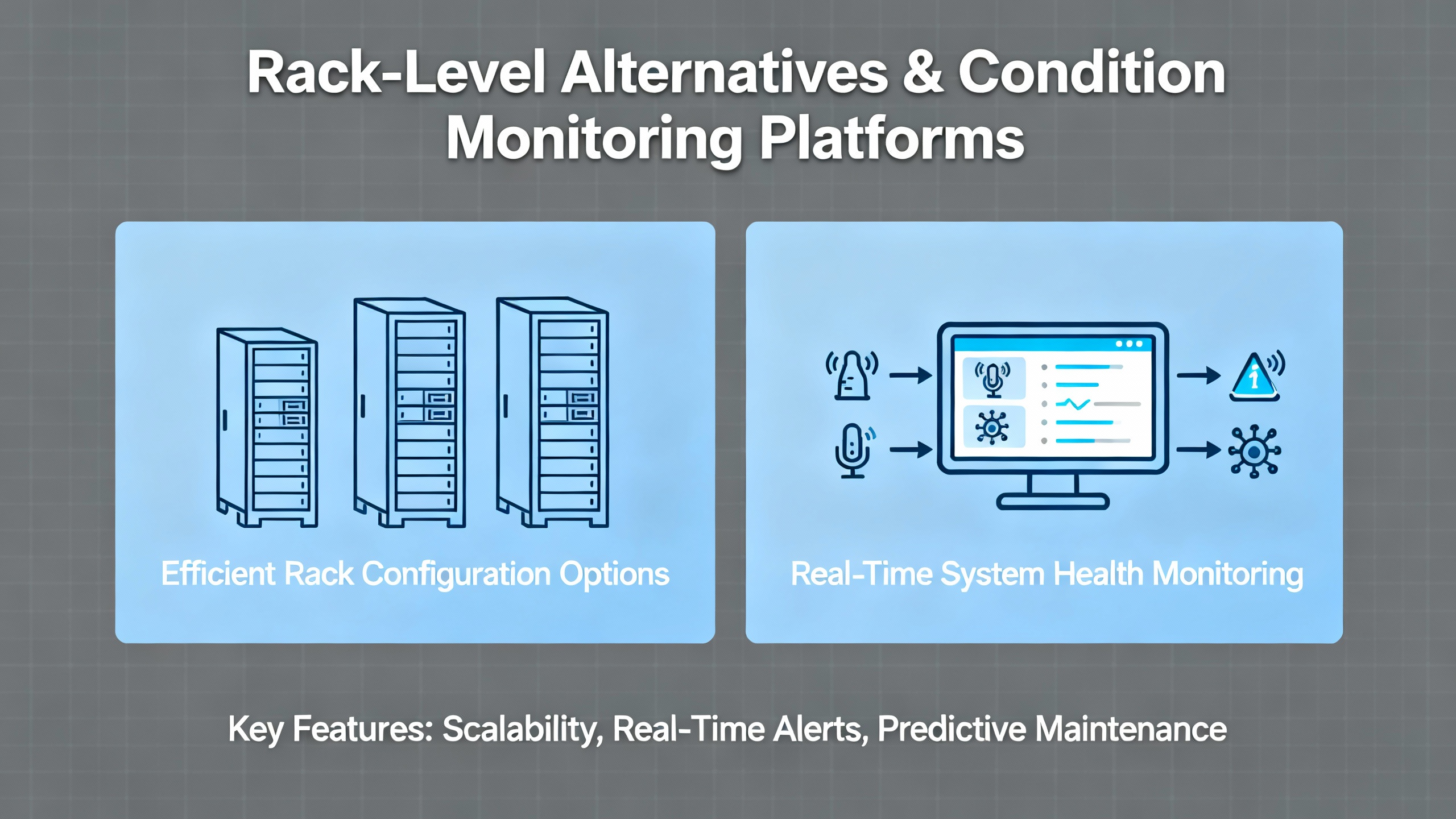

If you truly want to replace or avoid a Bently Nevada rack on a new project, you are looking for a vendor that can do two things well. They must provide reliable protectionŌĆæclass monitoring of critical rotating equipment and they must support plantŌĆæwide predictive maintenance.

Market research from sources such as MarketsandMarkets and Verified Market Research consistently names Baker Hughes (Bently Nevada), Emerson Electric, SKF, and Metrix as major players in this space. Here is how they compare in the context of a 3500/42M replacement strategy.

| Vendor or Platform | Role Relative to 3500/42M | Typical Strengths for Predictive Maintenance | Key TradeŌĆæoffs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metrix | LongŌĆæestablished vibration protection and monitoring supplier | Affordable protection technologies such as vibration switches, digital proximity systems, 4ŌĆō20 mA vibration transmitters, and highŌĆætemperature velocity sensors; strong fit for oil and gas, petrochemical, pipelines, power generation, cooling towers, and water/wastewater | Focus on simplicity and affordability; advanced analytics and multiŌĆætechnology integration depend on the rest of your system design |

| Emerson Electric | Integrated vibration transmitters and online condition monitoring systems | Offers vibration transmitters, online condition monitoring for power and water applications, and analyzers; strong diagnostics and case studies showing improvements such as 99.9 percent uptime on critical pumps | EnterpriseŌĆægrade solutions can be complex; you need to align EmersonŌĆÖs architecture with your existing DCS and asset management strategy |

| SKF | Broad condition monitoring and bearing expertise | Provides vibration measurement tools, tachometers, and other instrumentation; SKFŌĆÖs @ptitude software integrates machine condition data across the plant and supports early detection of issues | Excellent for rotating equipment fleets, but full protection rack equivalence depends on the specific hardware configuration chosen |

| National Instruments InsightCM | Flexible hardware plus serverŌĆæside condition monitoring | Offers continuous monitoring systems with up to twentyŌĆæeight wired accelerometer channels at up to 40 kHz and additional lowŌĆæfrequency channels, along with wireless vibration devices; InsightCM server centralizes data, provides waveform and spectral analysis, and supports multiple sensing technologies | Requires more engineering to configure than a fixedŌĆæfunction rack, but rewards you with flexibility and multiŌĆæsensor integration |

Metrix is often the first nonŌĆæBently name that comes up when plants want proven protection but are open to alternatives. With over sixty years of experience and innovations such as vibration switches, digital proximity systems, and 4ŌĆō20 mA vibration transmitters, Metrix systems are designed to provide early warning of unbalance, misalignment, wear, and looseness in a wide range of rotating and reciprocating machinery. Their equipment is widely applied in petrochemical plants, oil and gas pipelines, air separation units, power generation (including nuclear), cooling towers, and water and wastewater facilities. The emphasis in Metrix material is on preventing costly downtime, improving safety, and reducing repair costs through early intervention, rather than on elaborate analytics. For plants that want a straightforward rack and simple outputs into a PLC or DCS, Metrix can be a realistic 3500ŌĆæclass alternative.

Emerson approaches the problem from a slightly different angle. MarketsandMarkets describes how EmersonŌĆÖs vibration monitoring offerings span vibration transmitters, online condition monitoring systems, and analyzers. A LinkedIn analysis of vibration transmitters points out that Emerson is favored in harsh environments, with a case study where Emerson sensors installed on refinery pumps achieved about 99.9 percent uptime and longer maintenance intervals. Emerson ties vibration monitoring tightly into its broader control and asset management platforms, which makes it attractive if you already run Emerson DCS or asset management systems and want vibration to be part of that ecosystem.

SKF combines bearings, seals, and vibration monitoring. MarketsandMarkets notes that SKF supplies vibration measurement tools and condition monitoring solutions across industries such as oil and gas, automotive, aerospace, metals and mining, and food and beverages. Their @ptitude software suite is designed to bring machine condition data into one place, share it across plant functions, and enable early detection of equipment issues. When you are standardizing on SKF bearings and want a single vendor to provide both mechanical components and health monitoring, SKF becomes a natural alternative to a pure Bently rack.

National Instruments InsightCM is not a rack in the classic sense but a modular platform built around DAQ hardware and a server. The continuous monitoring system can handle up to twentyŌĆæeight wired accelerometer channels at sample rates up to 40 kHz along with hundreds of lowŌĆæfrequency channels. For predictive maintenance, this enables very highŌĆæfidelity measurements on critical machines and the ability to bring in other sensor types such as current, voltage, temperature, pressure, proximity, and tachometers. InsightCM software provides webŌĆæbased access, waveform trend and spectral analysis, and intelligent alarming that establishes baselines from known good data. NIŌĆÖs approach is compelling when you want a customizable condition monitoring system that can grow beyond vibration, although it does require more engineering than a turnkey rack.

For a new project with critical turboŌĆæmachinery, a conservative strategy is to compare a Bently 3500 solution against equivalent protectionŌĆæclass offerings from Metrix, Emerson, SKF, or an NIŌĆæbased architecture, while using your clarified predictive maintenance requirements to evaluate which vendor offers the best analytics, integration, and lifetime support.

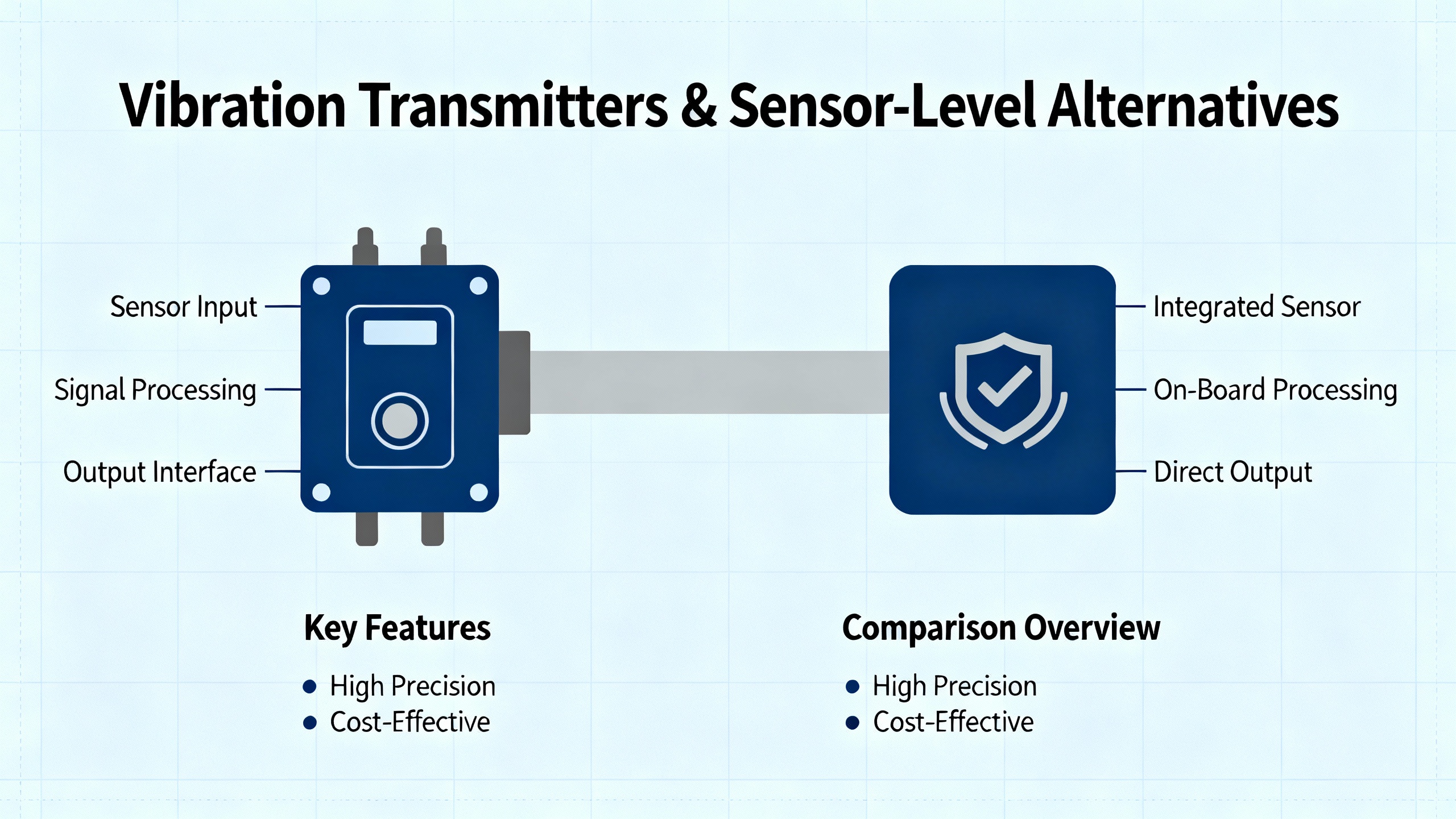

You do not always need or want a full rack. Many plants prefer to take vibration measurements into an existing PLC, DCS, or safety system via 4ŌĆō20 mA loops or digital fieldbuses and build their own alarming and trending on top. In that scenario, vibration transmitters and intelligent sensors effectively become your alternatives to 42M modules.

Metrix again is relevant here. Their history includes pioneering 4ŌĆō20 mA vibration transmitters and highŌĆætemperature velocity sensors. These devices measure overall vibration and convert it into a process signal that can be wired directly into standard analog input cards. For many pumps, fans, and blowers, this level of monitoring is sufficient to detect trends away from baseline and trigger work orders. The benefit is simplicity and low integration risk; you avoid specialized racks entirely and stay within the world your control engineers already understand.

Ifm electronic offers another practical pathway with their VV, VK, VT, and VN series vibration devices. The VV series sensors are designed for realŌĆætime monitoring of industrial machines and use IOŌĆæLink over your existing Ethernet infrastructure. Each VV device monitors four key failure categories: impact, fatigue, friction, and temperature, and can raise early alerts before they reduce availability. The VK and VT ranges combine an accelerometer and evaluation electronics in a single housing, measuring RMS velocity in the 10 to 1000 Hz band according to ISO 10816. They are intended to provide overall vibration monitoring through a simple, standardized method that is easy to integrate in machines. The VN family offers more flexibility, measuring overall machine vibration with configurable frequency ranges up to about 6000 Hz, and variants such as the VNB211 provide two configurable measurement outputs plus onboard trend history storage.

The practical implication is that if you have a strong PLC or DCS platform and a good historian, you can build a respectable predictive maintenance program using a combination of Metrix transmitters and ifm IOŌĆæLink vibration sensors, without installing a dedicated rack like the 3500/42M. The tradeŌĆæoff is that you typically monitor overall vibration or a few configured bands rather than capturing full broadband dynamic signals on every channel. For many lessŌĆæcritical pumps, motors, and fans, that is an acceptable compromise.

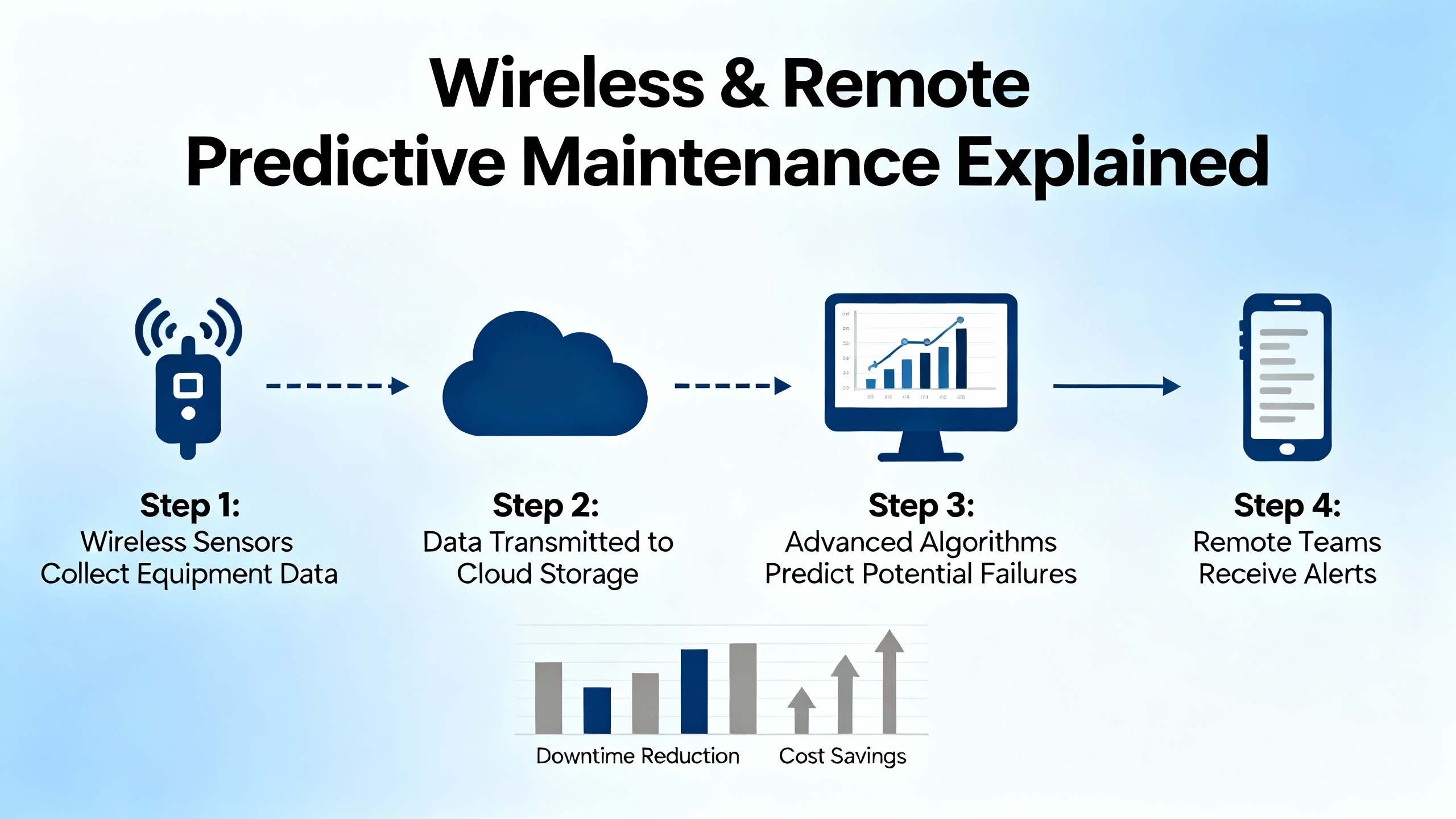

The fastest growth in vibration monitoring is not in traditional racks. Verified Market Research notes a shift from cabled accelerometers to wireless, batteryŌĆæpowered sensors, and projects a market growth rate of roughly 7.1 percent from 2021 to 2028. A Fluke overview of remote vibration sensors reinforces this, showing wireless devices monitoring motors, pumps, fans, blowers, compressors, conveyors, HVAC systems, and oilŌĆæfield pumps, streaming data to cloud software, and enabling technicians to work from safer, more convenient locations.

From a predictive maintenance standpoint, wireless systems are not a dropŌĆæin replacement for a 3500/42M, because they are not usually designed as primary protection devices. Instead, they offer a powerful overlay that can extend your monitoring coverage far beyond what a rack can feasibly handle.

Several wireless ecosystems stand out in the research.

Lord SensingŌĆÖs MicroStrain line, discussed in detail by an enDAQ technical review, includes the GŌĆæLINKŌĆæ200 integrated wireless accelerometer and the IEPEŌĆæLINKŌĆæLXRS node for external piezoelectric accelerometers.

The GŌĆæLINKŌĆæ200 is a rugged triaxial accelerometer with a sample rate up to 4 kHz and bandwidth up to about 1 kHz. It offers selectable ranges of 8 g or 40 g, low noise, a builtŌĆæin temperature sensor, multiple sampling modes including continuous, burst, and eventŌĆætriggered, and 16 MB of onboard storage. The device measures roughly 1.8 by 1.7 by 1.7 inches, runs on two halfŌĆæAA batteries, operates from about ŌłÆ40┬░F to approximately 176┬░F, and carries an IP67 rating. A 2.4 GHz radio (IEEE 802.15.4) provides indoor ranges around 160 feet and outdoor ranges up to roughly half a mile. The review estimates node pricing in the $500 to $1,000 range, although this is an educated guess rather than list price.

For higherŌĆæfrequency needs, the IEPEŌĆæLINKŌĆæLXRS node connects a single highŌĆæend IEPE accelerometer with 24ŌĆæbit resolution and sample rates up to 104 kHz in periodic burst mode. A 650 mAh rechargeable battery can last on the order of forty days at 10 kHz sampling for fiveŌĆæsecond bursts taken every hour, based on the vendorŌĆÖs battery life calculator.

Both nodes connect through gateways, such as the WSDAŌĆæ2000, into the SensorCloud platform. SensorCloud provides customizable dashboards, email and SMS alerts based on vibration thresholds or missing data, Python Jupyter notebooks for advanced analysis, and an API for data upload and download. According to the review, SensorCloudŌĆÖs pricing is published and structured per gateway, with free, $35, and $100 per month tiers, and higher tiers supporting roughly one billion data points (about 2 GB) per gateway.

In practice, I consider MicroStrain plus SensorCloud when I need a robust, waterproof, longŌĆærange solution on outdoor assets where running cables back to a 3500 rack or PLC cabinet is impractical. The strengths are instrumentationŌĆægrade sensors and a transparent, developerŌĆæfriendly cloud platform.

PCB Piezotronics, now part of MTS, is a longŌĆærespected manufacturer of piezoelectric accelerometers and other dynamic sensors. Their Echo Wireless solution, described in the same enDAQ review, centers on a wireless accelerometer with a height around 4.4 inches, a diameter near 1.7 inches, a frequency range of 4 to 2300 Hz, an amplitude capability up to 20 g, and a fine resolution of about 0.007 g. The mass is approximately 1 pound, and it communicates via ISMŌĆæband wireless around 916 or 868 MHz.

On the software side, Echo Wireless stores data locally in a SQL database on a server or PC. That architecture has the advantage of keeping data on site for security but provides less inherent cloudŌĆæbased remote access. The application supports viewing historical data as graphs and metrics and allows users to configure warning and alarm conditions, although the reviewer notes that some other systems apply machine learning to detect changes automatically.

Echo Wireless is a good fit when you already trust PCBŌĆÖs sensors and prefer to keep vibration data within your own infrastructure, for example in a facility that is cautious about cloud services.

enDAQŌĆÖs WŌĆæSeries, launched around 2020 and described at length by its own product blog, takes a slightly different approach. The devices are built to record and upload very large volumes of data directly to enDAQ Cloud over WiŌĆæFi. There are two main form factors: a thinner version with a 1.25 Ah battery and a thicker version with a 4 Ah rechargeable battery. Each format offers multiple variants based on accelerometer type and range, covering digital capacitive accelerometers with a 40 g range at 4 kHz sampling, piezoelectric accelerometers with 25 g, 100 g, or 2000 g ranges at 20 kHz sampling, and piezoresistive accelerometers with 500 g or 2000 g ranges at 20 kHz sampling.

Every unit contains at least one triaxial accelerometer and most contain two so that vibration and shock can be measured in the same device. Additional sensors include a gyroscope, temperature, pressure, humidity, and light, with GPS and microphone hardware present and awaiting firmware support. Triggering options combine timeŌĆæbased and sensorŌĆæthreshold conditions, and continuous recording can also be started with a simple button. Each unit carries 16 GB of onboard memory, storing roughly eight billion data points, and the physical footprint is about 3.9 by 2.3 inches, with a height of either approximately 0.7 or 1.8 inches depending on battery size. The operating temperature range is specified from roughly 104┬░F up to about 176┬░F, and the standard enclosure carries an IP50 rating, with a waterproof accessory planned.

enDAQ Cloud can accept automatic uploads from wireless devices or manual uploads from nonŌĆæwireless instruments. Users can build fully customized dashboards, including their own analysis algorithms and visualizations, and the platform provides builtŌĆæin metrics such as RMS acceleration, velocity, displacement, sound levels, rotation, peak acceleration, pseudo velocity, average temperature, pressure, and GPS speed and location. Email alerts can be configured on various thresholds, and an open API exposes both summary metrics and raw data. Reports can be shared via links, and files can be organized by tags. Pricing is publicly listed, with a generous free tier that includes a substantial amount of storage and standard reports, and paid tiers that add API access and custom reporting.

I reach for enDAQ when a team wants highŌĆæfidelity data, a rich set of auxiliary sensors, and deep customization in the cloud, particularly during development of new analytics or when characterizing complex vibration environments.

A critical caution about wireless alternatives comes from KCF Technologies, whose detailed analysis of wireless vibration sensor mechanics shows that many popular devices suffer from serious measurement errors due to poor mechanical stability. In controlled shakerŌĆætable tests, they adjusted sensor mass and center of mass height and compared outputs against a reference accelerometer from a benchmark wired sensor. They found that peak error in transverse vibration could range from about 60 percent to as high as 410 percent for common configurations, even when the sensor was mounted on an ideal, rigid surface.

KCF identified three simple physical parameters that largely determine stability and accuracy: total mass, height of the center of mass above the mounting surface, and width of the mounting base. They proposed an ŌĆ£Instability Index,ŌĆØ essentially the product of mass and centerŌĆæofŌĆæmass height divided by base width, and demonstrated that higher values correlate with higher measurement error. Their own VSN3 sensor, aided by a low center of mass and a patented DARTwireless technology that reduces power consumption by up to eight times, approaches the mechanical stability of a wired benchmark accelerometer, while many other wireless sensors exhibit much higher instability.

For predictive maintenance, the implications are serious. Bearing fault frequencies are often in the 10 to 1000 Hz band for a typical 1800 RPM motor, right where sensor resonances and mechanical instabilities can create large errors. BaselineŌĆæbased analytics may hide this until a fault develops, at which point amplitudes can be falsely amplified or suppressed. KCF therefore recommends, and I strongly agree, that end users should evaluate wireless sensor mechanical design, favoring low mass, low center of mass, wide bases, and accelerometers located as close to the mounting surface as possible, rather than relying solely on the internal accelerometer datasheet.

National Instruments, in addition to its wired continuous monitoring systems, offers a wireless vibration measurement device and a fully integrated wireless vibration sensor that feed into InsightCM. The twelveŌĆæchannel wireless measurement device accepts traditional piezoelectric accelerometers at up to 10 kHz sampling and can run on batteries, with logic to sense whether a machine is running before recording and uploading data. The singleŌĆædevice wireless sensor integrates a triaxial accelerometer, temperature sensing, battery, and wireless connectivity, supports sample rates up to about 2 kHz, and carries an IP67 rating. Both funnel data into the same InsightCM server that the wired systems use.

In plants where you already have a Bently 3500 rack protecting the most critical machine train, a pragmatic strategy is to leave that protection in place, augment it with NI wireless sensors on surrounding equipment, and use InsightCM as a common analytics and visualization layer. This preserves the proven reliability of the rack while extending predictive maintenance coverage to assets that would never justify a fullŌĆæblown protection system.

Once you understand the landscape, the practical question becomes how to move forward without putting your plant at risk or overwhelming your team.

One proven approach, highlighted implicitly in the control.com discussion about replacing the Bently 3500, is to treat Bently as your reference point while still obtaining competitive quotes. You specify the monitoring and protection requirements that a 3500/42M system would meet, and then you invite vendors such as Metrix, Emerson, SKF, and NI to show how they would meet or exceed those requirements. The decision then follows a mixture of technical evaluation, lifecycle cost, and organizational fit.

For plants that already have a Bently rack in place, the riskŌĆæaware path is to leave the rack dedicated to protection and add predictive maintenance capabilities alongside it. That may mean adding Metrix or ifm vibration transmitters wired into a PLC to monitor lessŌĆæcritical pumps and fans, or deploying wireless systems such as MicroStrain, PCB Echo, enDAQ, KCF, or NI wireless sensors on assets that are physically remote or hard to reach. InstrumartŌĆÖs guidance, along with commentary from Augury and AdvancedTech, supports the idea that vibration monitoring is most powerful when it is pervasive, tied into broader asset data, and used to drive conditionŌĆæbased maintenance.

When designing a wireless vibration program across multiple sites, the SMRP Exchange experience is useful. Define your minimum sensor specifications in terms of maximum frequency, resolution, and battery life. Ensure that the software environment provides familiar vibration plots and tools so your analysts can work effectively. Demand integration pathways to your CMMS and to other condition monitoring technologies. Perhaps most important, remember that wireless vibration sensors are the starting point of a predictive ecosystem, not the entire solution. You will still need human expertise, process data, and clear workflows for how an alarm becomes a work order and then a completed job.

Finally, be wary of treating any vendor, including Bently Nevada, as a magic bullet. The market research from Verified Market Research, MarketsandMarkets, and others makes it clear that many vendors now offer capable vibration monitoring and predictive maintenance solutions. Baker Hughes, Emerson, SKF, Metrix, National Instruments, Fluke, ifm, and KCF all bring different strengths. The plants that get the most value from these systems are the ones that invest as much effort in their maintenance strategy, data integration, and human processes as they do in the hardware.

For safetyŌĆæcritical turboŌĆæmachinery, the answer is generally no. The 3500/42M is part of a protection rack that is designed to trip machines when vibration exceeds safe limits. Wireless systems described in sources such as Fluke, enDAQ, and KCF are excellent for predictive monitoring and remote diagnostics, but they are not typically certified or architected as primary protection systems. A more realistic design keeps the rack for protection and uses wireless sensors to broaden predictive coverage.

There is no universal best choice. A Metrix system may be ideal if you want an affordable, protectionŌĆæoriented rack and transmitters tied into a PLC. Emerson or SKF may be better if you want vibration tightly integrated with broader control and asset management platforms. National Instruments may be preferred if you need high channel counts, high sample rates, and multiŌĆætechnology integration. Wireless ecosystems such as MicroStrain, PCB Echo, enDAQ, KCF, and Fluke are strongest when you need flexible deployment and remote access. Your equipment criticality, existing infrastructure, and organizational skills will drive the right combination.

The KCF Technologies study is a good reference point. Look beyond the accelerometer chip datasheet and pay attention to mechanical design. Favor sensors that are physically stable, with low overall mass, a low center of mass, and a wide mounting base. Ask vendors for transmissibility data or error characterization across your frequency band of interest. Combine this with the SMRP guidance on minimum specifications (such as maximum frequency and resolution) and with your battery life and installation requirements.

In the field, I have found that the most reliable outcomes come from treating platforms like the Bently 3500/42M as one component in a layered strategy. You keep robust protection where it matters, deploy wired transmitters and IOŌĆæLink sensors where they are costŌĆæeffective, and fill in the gaps with carefully chosen wireless systems. Done that way, alternatives to Bently Nevada do not weaken your monitoring; they extend it, making your predictive maintenance program far more capable than a rack alone could ever be.

Leave Your Comment