-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for ŌĆ£ŌĆØ.

In a chemical plant, the control system is not just another project line item. It is the nervous system that keeps reactions stable, prevents runaway conditions, and keeps operators from fighting the plant every shift. Distributed control systems (DCS) have been the backbone of process industries for decades, particularly in chemicals, refining, and power, because they are designed for continuous and batch processes that must run safely and efficiently around the clock.

Industry guidance from organizations such as the International Society of Automation and Chemical Engineering Progress emphasizes that selecting a control system is a strategic decision. Systems often remain in service for twenty years or more, and they directly affect uptime, maintenance costs, energy use, and the plantŌĆÖs ability to adapt to new products or regulatory changes. Authors from Honeywell Process Solutions and CONTROL magazine underline that there is no universally ŌĆ£bestŌĆØ system; the right DCS controller is the one that best satisfies your specific technical and business requirements.

As someone who has had to troubleshoot production losses and near-misses caused by weak control architectures, I treat DCS controller selection as a safety and reliability decision first, and a purchase decision second. The controller you choose will govern how well your chemical plant handles disturbances, how gracefully it fails, and how painful every future modification will be.

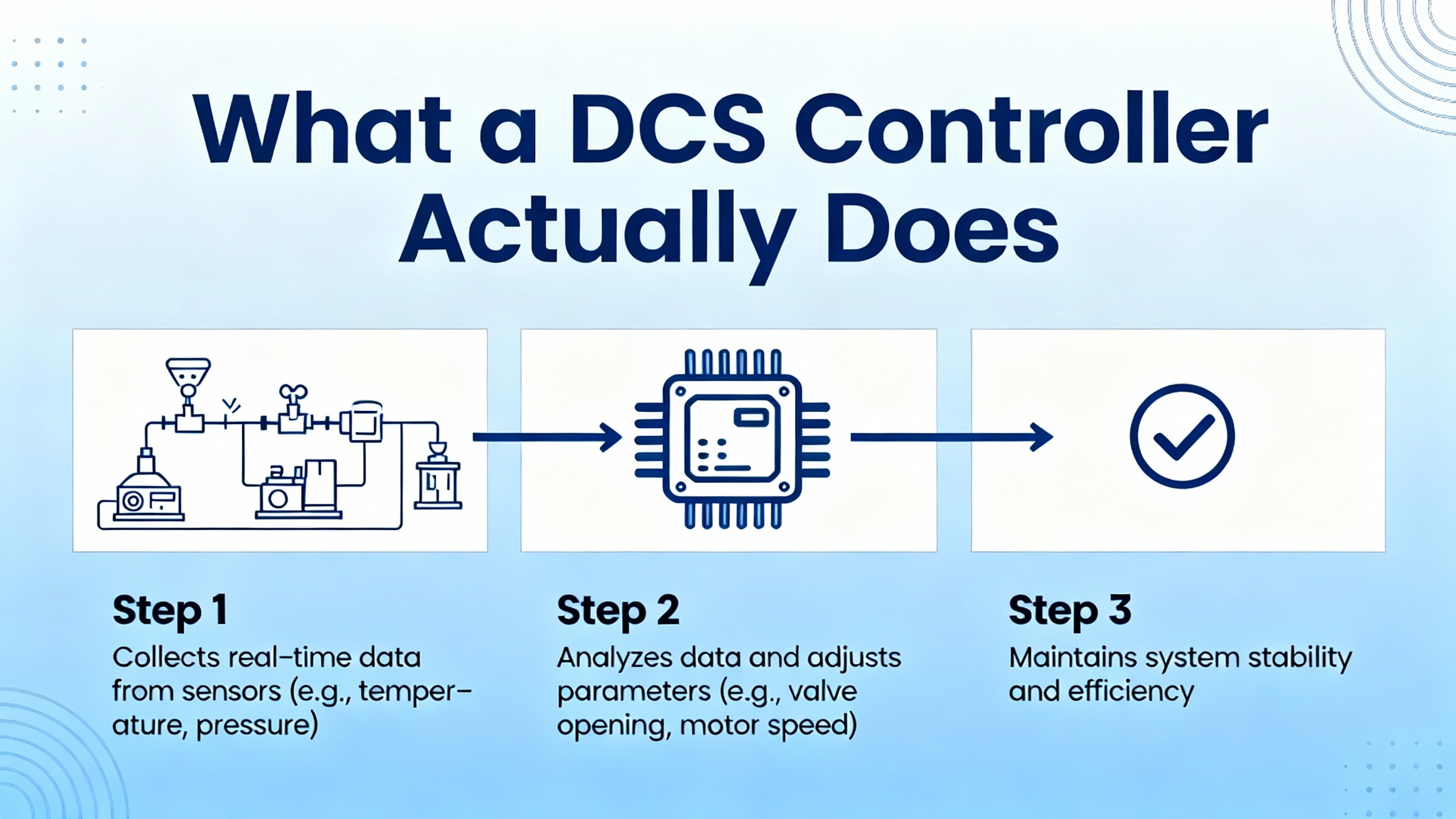

A DCS controller is a microprocessor-based unit that executes the control logic for a segment of the plant. According to descriptions used in industrial security frameworks such as MITRE ATT&CK, each controller typically manages one area or function of a continuous process while participating in a larger DCS network. Field sensors send temperature, pressure, flow, and composition signals into the controller; the controller runs regulatory and advanced algorithms and sends outputs to valves, drives, and other actuators. Multiple controllers, operator stations, engineering workstations, and servers form the overall DCS architecture.

Chemical plants favor this distributed approach because it scales. You can add controllers as the plant grows in scope and complexity, rather than overloading a single central processor. This distribution also provides redundancy: if one controller fails, the others continue to operate, which improves overall reliability and stability. Modern DCS controllers are typically programmed using IEC 61131-conforming languages such as function blocks and structured text, which align well with process control strategies.

In chemical service, DCS architectures go further than basic control. Articles focused on chemical plants highlight that the DCS continuously monitors critical parameters and automatically intervenes when values move outside safe operating ranges. The system can trigger alarms, sequence shutdowns, and coordinate interlocks across equipment that would be extremely difficult to manage manually. Integration with safety instrumented systems, emergency shutdown logic, and plant historians turns the DCS into the core safety and optimization platform for the facility.

The most common question in early design reviews is whether a chemical plant really needs a DCS controller, or whether high-end programmable logic controllers (PLCs) with SCADA and HMI will suffice. Control Engineering, Plant Engineering, and several practitioners on professional forums draw a consistent distinction.

PLCs are rugged industrial computers that excel at high-speed discrete logic, machine control, and standalone skids. They are ideal for tasks such as packaging, material handling, and fast sequences, and they can also support a moderate number of analog loops. A PLC-based system usually relies on separate HMI or SCADA software for visualization and alarms. This suits small systems with limited I/O counts and minimal integration requirements.

A DCS, on the other hand, is designed as a plant-wide platform. It combines multiple distributed controllers with a common operator environment, shared system database, native historians, alarm management, and asset management. Authors in Control Engineering and CrosscoŌĆÖs application notes emphasize that this single database and integrated engineering environment make DCS platforms much easier to manage as the plant grows and changes.

Hybrid systems blur the line. Plant Engineering notes that over the past decade and a half, PLC and DCS vendors have converged in capability. PLCs can now handle more regulatory loops with better redundancy, and DCS vendors have added stronger discrete control and lowered hardware costs. Vendors and integrators now offer hybrid or ŌĆ£DCS-likeŌĆØ systems that combine DCS-style redundancy and data management with PLC speed and openness.

For a modestly sized, simple chemical unit with perhaps a few hundred I/O points, limited loop count, and no central control room, a PLC with local HMI may be entirely appropriate. Once you move into multi-unit production, large numbers of PID loops, complex interlocks, and 24/7 operations, the balance shifts toward a DCS controller as the primary process control platform, with PLCs supporting discrete or safety functions where very high-speed sequencing is required.

Published selection guides and field experience point to several recurring factors that tilt the decision toward a DCS controller in a chemical environment.

One factor is process complexity and loop count. Plant EngineeringŌĆÖs ŌĆ£six stepsŌĆØ for choosing between PLC and DCS explains that regulatory loops consume significant CPU and memory in PLCs. Even powerful PLCs reach a practical limit after a few hundred loops, especially when they also have to run complex discrete logic. DCS architectures distribute loops across multiple controllers while sharing data, making it straightforward to handle large loop counts without jeopardizing scan times.

Another factor is advanced process control and optimization. Industry practitioners writing on LinkedIn and in vendor white papers stress that if you require advanced techniques such as model predictive control, adaptive tuning, or multivariable optimization to maintain product quality and maximize yield, a DCS is usually the natural choice. Distributed control systems are built to host advanced control and optimization applications near the process, often on specialized servers or controllers, while maintaining tight integration with operator displays and historians.

Operator environment and control room requirements matter as well. For plants that do not have a centralized control room and operate more like packaged units, a PLC plus a small HMI panel or industrial PC is often sufficient and more economical. Large chemical facilities typically use a staffed control room where operators must monitor and interact with the process continuously. In that scenario, DCS platforms provide integrated HMI hierarchies, consistent faceplates, alarm summaries, and navigation patterns. Honeywell Process Solutions and other DCS suppliers highlight human-factors guidance, such as Abnormal Situation Management principles, to improve situational awareness and operator performance.

Modification frequency and lifecycle changes also favor DCS controllers in many chemical plants. Because DCS platforms maintain a single integrated database for control logic, graphics, alarms, and historical tags, changes can be engineered and tested more coherently. Plant Engineering and Control Engineering note that PLC plus SCADA solutions often involve multiple variable databases across PLCs, SCADA servers, and middleware, which makes frequent modifications more time-consuming and error-prone. If you expect to add units, change recipes, or reconfigure operating modes regularly, the DCS engineering environment can significantly reduce lifecycle engineering effort and risk.

Finally, availability requirements must guide your choice. Continuous process plants often need near-constant availability, and restarts after trips can be slow and hazardous. Control Engineering, GlobalSpec, and World of Instrumentation emphasize that DCS architectures are built for high availability, with redundant controllers, networks, servers, and power supplies. Many chemical producers also require online upgrades, online configuration changes, and the ability to run mixed software versions without stopping the process. It is not that PLCs cannot be made redundant; it is that DCS controllers and their surrounding architecture make redundancy the default rather than a custom project.

Chemical plants run inherently hazardous operations: high pressures, flammable and toxic materials, exothermic reactions, and complex thermal management. Several sources focused on chemical industries describe DCS-based control as central to managing this risk.

A DCS-based architecture continuously monitors critical process variables and executes safety-related logic when values drift outside defined operating envelopes. Articles on DCS in chemical plants explain that the system can automatically intervene by shutting down equipment, triggering alarms, or moving the process to predefined safe states. The key point is that control and safety logic in the DCS work consistently across the plant, rather than being a patchwork of local protective functions.

Redundancy is the first visible safety feature in a DCS controller. GlobalSpecŌĆÖs selection guide explains that DCS architectures commonly use backup processors and duplicated elements so that a single failure does not cause loss of control. World of Instrumentation goes further, describing typical design targets such as extremely high system availability, stringent mean time to repair, and very long mean time between failures, supported by redundancy in communication networks, controllers, mass storage, power supplies, I/O cards, operator workstation network cards, and hubs. For a chemical plant, the practical interpretation is straightforward: your ŌĆ£bestŌĆØ DCS controller should be available in redundant configurations, and the system architecture around it should also be redundant from field wiring up to servers.

Electrical isolation and grounding play a safety role as well. Guidance on DCS specification stresses galvanic isolation for field instrument and external signals, separate grounding for DCS and field systems to minimize noise, and additional isolation between operator or engineering workstations and controllers to protect against surges. These practices reduce the risk that electrical faults propagate into control electronics, which in turn reduces spurious trips and dangerous mis-operations.

Access control is another core safety factor. World of Instrumentation describes multi-level access control with different keys or passwords for operator, supervisor, and engineering roles, including automatic reversion to operator-level rights when higher-level keys are removed. In practice, that means your DCS controller and associated software should allow you to lock down who can change logic, setpoints, and alarms, and to maintain a clear audit trail of changes. Pharmaceutical-focused DCS selection guidance reinforces the need for encryption, authentication, authorization, audit trails, and backup and recovery mechanisms, not just for data integrity but for regulatory compliance.

Chemical plants also depend heavily on integrated alarm management. Honeywell and other vendors recommend features such as prioritized alarms, exception-based monitoring, and alarm analytics. Healthier alarm systems reduce the chance that operators will miss a critical warning during a busy upset. A DCS controller that tightly integrates alarms with control logic and operator graphics makes it much easier to implement effective alarm rationalization and advanced alarming strategies.

Finally, integration with safety instrumented systems and emergency shutdown logic must be considered. Best-practice discussions in the chemical sector routinely describe DCS platforms that are tightly coupled with safety systems, fire and gas detection, and machine monitoring, while still respecting appropriate separation and independence. The goal is coordinated behavior: when a safety system trips a unit, the DCS controller should understand what happened, manage the rest of the plant appropriately, and provide clear diagnostics to the operator.

Safety alone does not keep a plant competitive; it needs to run efficiently as well. Chemical plants benefit when the DCS controller and surrounding system support continuous optimization, smart maintenance, and good human performance.

Process efficiency starts with better control. Articles on DCS in chemical manufacturing describe how real-time optimization of temperature, pressure, flow, and other variables reduces raw material waste, stabilizes operation, raises throughput, and frees operators from constant manual adjustments. Pharmaceutical DCS selection guidance highlights advanced process control and optimization of key variables to achieve desired product quality and maximize batch yield. To support these capabilities, your DCS controller should be powerful enough to execute advanced algorithms and to exchange data rapidly with higher-level optimization applications.

Operator usability and abnormal situation management also influence efficiency. Honeywell Process Solutions and the ASM Consortium emphasize the value of standard display libraries, pre-built equipment templates, multi-level display hierarchies, and one-click navigation between related windows. When a controller upset occurs, operators must be able to understand the plant state and act within seconds. A DCS that supports exception-based monitoring, context-rich displays, and consistent graphics reduces response times and helps avoid minor issues turning into unit shutdowns.

Engineering efficiency is another dimension. HoneywellŌĆÖs work on advanced DCS solutions describes unified engineering and operations environments with a single database for control logic, HMI graphics, alarms, and history. Combined with bulk configuration tools and reusable templates, this reduces configuration effort, eliminates data duplication, and minimizes mismatches between engineering and operations views. For a chemical plant that expects to add units or regularly tweak recipes, this translates directly into lower cost and shorter project schedules when changes are needed.

Data and enterprise integration drive both efficiency and business alignment. DCS guides from GlobalSpec and World of Instrumentation mention open interfaces to management information and business systems using TCP/IP-based links and standards such as OPC and COM. ConfluentŌĆÖs materials on DCS integration take this further by positioning real-time data streaming from DCS components into enterprise systems like ERP and inventory management as a way to optimize supply chains, reduce waste, and improve overall operational efficiency. In practice, this means you should select a DCS controller and platform that can expose real-time and historical data securely to higher-level systems without fragile point-to-point integrations.

Finally, predictive and proactive maintenance depends on rich diagnostic data. Articles on DCS in chemical plants emphasize real-time diagnostics that help identify equipment issues early, reduce unplanned downtime, and extend equipment life. Modern DCS controllers and networks take advantage of smart field devices, digital protocols, and embedded diagnostics. Plant Engineering also points out that many users still underuse the diagnostics available in intelligent field devices; the right DCS platform makes it easier to visualize and act on that information across the plant.

Practitioners writing in CONTROL magazine caution against choosing a DCS based on opinions or brand loyalty. Instead, they recommend a structured process: model the plant, design the control scheme, write an engineering specification, derive a list of requirements, and evaluate each candidate system against that list. Industry white papers from automation suppliers such as Honeywell and Yokogawa reinforce that the ŌĆ£bestŌĆØ control system is the one that best aligns with your defined operational and business objectives.

The table below summarizes critical selection areas that consistently appear in chemical-industry guidance and vendor-neutral articles.

| Selection area | What to look for in a chemical DCS controller | Why it matters for safety and efficiency |

|---|---|---|

| Process control and APC capability | Ability to handle large numbers of regulatory loops across multiple controllers, with support for advanced process control and optimization | High loop counts and multivariable interactions are typical in chemical plants; DCS architectures scale better than PLCs and are designed to host advanced control that stabilizes processes and improves yield |

| Safety and availability | Redundant controller options, redundant networks and power, galvanic isolation, realistic design targets for availability, MTTR, and MTBF | Chemical plants need near-continuous operation and safe failure behavior; redundancy and robust hardware design reduce the risk of trips and make recovery faster and safer |

| Engineering and HMI environment | Single, shared database for logic, graphics, alarms, and history; standard display libraries; bulk configuration and templates | Integrated engineering tools reduce errors and project effort; consistent graphics and navigation improve operator performance during both normal operation and upsets |

| Cybersecurity and access control | Multi-level user roles, strong authentication and authorization, built-in firewalling, centralized antivirus or endpoint protection, secure remote-access options | Threats to control networks are growing; built-in security and access control protect safety and production data and support compliance requirements |

| Integration and openness | Support for standard industrial networks and protocols such as Ethernet, OPC-based interfaces, and well-defined APIs; roadmap toward more open, interoperable architectures | Open connectivity makes it easier to integrate with existing PLCs, smart instruments, historians, and enterprise systems while reducing vendor lock-in and easing future upgrades |

| Lifecycle support and staffing | Vendor commitment to long-term support, clear migration paths, training options for plant staff, and availability of capable integrators | Control systems can remain in service for decades; lifecycle support, local expertise, and maintainability determine total cost of ownership and upgrade flexibility |

Once these criteria are defined for your process, the evaluation becomes more objective. It is entirely reasonable, for example, to require that after commissioning no more than a certain percentage of controller CPU and network capacity be used under normal loads, that a given fraction of I/O modules and communication ports remain as installed spares for future expansion, and that the DCS vendor commit to specific upgrade paths. World of Instrumentation suggests practical targets such as maintaining around one-fifth spare I/O and power capacity and keeping controller loading comfortably below saturation so future expansions do not require wholesale replacement.

Cybersecurity criteria deserve the same level of rigor as process control features. Guidance on DCS protection calls for robust, industry-proven firewalls, centrally managed antivirus hosted on the engineering workstation, and structured processes for patch distribution across the system. Materials from Mingo Smart Factory and open automation initiatives also stress strong access control, regular security audits, and training to help staff recognize and mitigate threats. For any DCS controller under consideration, you should review not just its protocol support but also its hardening guidelines, supported security standards, and vendor patching practices.

Finally, vendor selection must be treated as a separate decision dimension. YokogawaŌĆÖs control-system selection guidance notes that vendor criteria extend well beyond initial cost and should include service network strength, roadmap transparency, software licensing practices, and the ability to support distributed or phased construction projects. Plant EngineeringŌĆÖs discussion of staffing models adds that some vendors rely heavily on integrator networks, while others deliver more of the engineering directly at higher day rates. Training in-house staff to maintain and modify the DCS can significantly reduce long-term cost, but it requires upfront investment that should be factored into the selection.

In chemical projects that go well, the selection of the DCS controller follows a disciplined engineering workflow rather than a marketing-driven one. Contributions in CONTROL magazine outline one practical approach that aligns with what many experienced engineers do in the field.

The work starts with understanding the process itself. Teams build a detailed simulation or model of the planned plant using process simulators so they can explore dynamics, interactions, and upset behavior. From this, they derive the complete control scheme: every loop, interlock, sequence, and override needed for safe and efficient operation. This is not just a list of PIDs and onŌĆōoff valves; it is the full picture of how the plant should respond to normal changes in feed and product, to disturbances, and to equipment failures.

With that control scheme in hand, they write an engineering specification for the control system. This specification describes not only I/O counts and controller response times but also advanced control needs, asset management expectations, alarm management philosophies, operator assistance tools, cybersecurity requirements, and integration points with enterprise systems. It also spells out expectations for redundancy, spare capacity, and future expansion.

From the specification, the team derives a clear, itemized list of requirements. Each requirement can then be used to evaluate candidate DCS platforms. Instead of debating brands in the abstract, the selection team scores how well each system satisfies the requirements. Walt Boyes of CONTROL magazine describes this as counting ŌĆ£check marksŌĆØ: the system that satisfies the most requirements is the best fit for that plant, in that context. Crucially, this evaluation treats DCS controllers and PLC-based architectures as alternative ways to meet the same requirements, not as brands to be defended.

Separately, the project team evaluates the vendor or integrator. They consider lifecycle support commitments, training capabilities, experience with similar chemical processes, and alignment with any corporate standards for open architectures. Guidance from the Open Process Automation Forum and AIChE highlights that closed, proprietary DCS designs have historically caused high replacement and refresh costs and made third-party integration difficult. Open-architecture initiatives such as the Open Process Automation Standard aim to enable interoperability and interchangeability of components from multiple suppliers. Even if you are not ready to adopt a fully open architecture, it is wise to ask vendors about their roadmap for standards-based connectivity, portability of configurations, and support for multi-vendor environments.

This engineering-led approach does not guarantee perfection, but it does something more important: it forces you to articulate what ŌĆ£bestŌĆØ means for your plant in terms of safety, performance, flexibility, and lifecycle economics, and then to prove that the chosen DCS controller can actually deliver it.

Yes, in some cases. Discussions in Control Engineering, Plant Engineering, and CONTROL magazine agree that smaller plants with relatively few loops, simple processes, and limited integration requirements can run successfully on PLC-based systems, often with a local HMI or a modest SCADA layer. These solutions typically cost less upfront and are familiar to many in-house technicians. However, once the number of regulatory loops grows, advanced process control becomes desirable, or frequent modifications are expected, the trade-offs shift. At that point, a DCS controller with its distributed architecture, single database, and richer engineering tools usually provides better safety, easier expansion, and lower lifecycle effort.

Redundancy should match the risk and the economic impact of downtime. Guidance from GlobalSpec and World of Instrumentation describes DCS designs that use redundant controllers, communication networks, power supplies, and I/O for critical loops, along with design targets aimed at extremely high availability and long mean time between failures. Many chemical plants at least duplicate controllers and networks in high-hazard units and ensure that power, communications, and key operator stations are not single points of failure. A practical rule used in specifications is to keep controller CPU and network loading comfortably below full capacity and to install spare I/O modules, racks, and communication ports so that adding loops or replacing faulty components does not jeopardize redundancy or require major redesign.

The answer depends on your tolerance for vendor lock-in and your long-term modernization plans. AIChEŌĆÖs coverage of the Open Process Automation Forum points out that traditional DCS platforms have often been tightly coupled and proprietary, making upgrades and third-party integration expensive. Open-architecture initiatives and standards aim to enable interoperable, multi-vendor systems where components and software can be interchanged more freely. Even if you are not ready to deploy a fully open system, it is wise to select a DCS controller and platform that support widely used standards such as IEC 61131-based programming and OPC-style connectivity and that have a clear roadmap toward more open, interoperable architectures. This will make future migrations, analytics initiatives, and multi-vendor integrations far easier.

If you are responsible for a chemical plant, the ŌĆ£bestŌĆØ DCS controller is the one that quietly keeps operators out of trouble for decades: it protects people and equipment, it lets you adapt the plant without fear, and it never forces you into a corner when technology or business needs change. From the field, the projects that succeed are always the ones where the team did the hard engineering work up front, defined what they needed in safety and efficiency terms, and then made the controller prove it could deliver before they ever signed a purchase order.

Leave Your Comment