-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for ŌĆ£ŌĆØ.

When a CompactRIO drops off the network ten minutes before a production run, it stops being an embedded controller and becomes a very expensive brick. I have seen CompactRIO systems sitting at the heart of advanced 3D PCB inspection, realŌĆætime turbine condition monitoring, and university labs teaching PID control on DC motors. In those environments, you do not have the luxury of ŌĆ£weŌĆÖll debug it next week.ŌĆØ You need a structured, defensible way to troubleshoot and recover quickly.

This article walks through a practical troubleshooting approach for National Instruments (NI) CompactRIO systems, grounded in NI documentation, NI knownŌĆæissues bulletins, community experience, and realŌĆæworld case studies. The focus is on what you can actually do in the field: how to get a controller back on the network, interpret odd behavior around modules and FPGA builds, recognize known bugs, and avoid turning a minor issue into a multiŌĆæday outage.

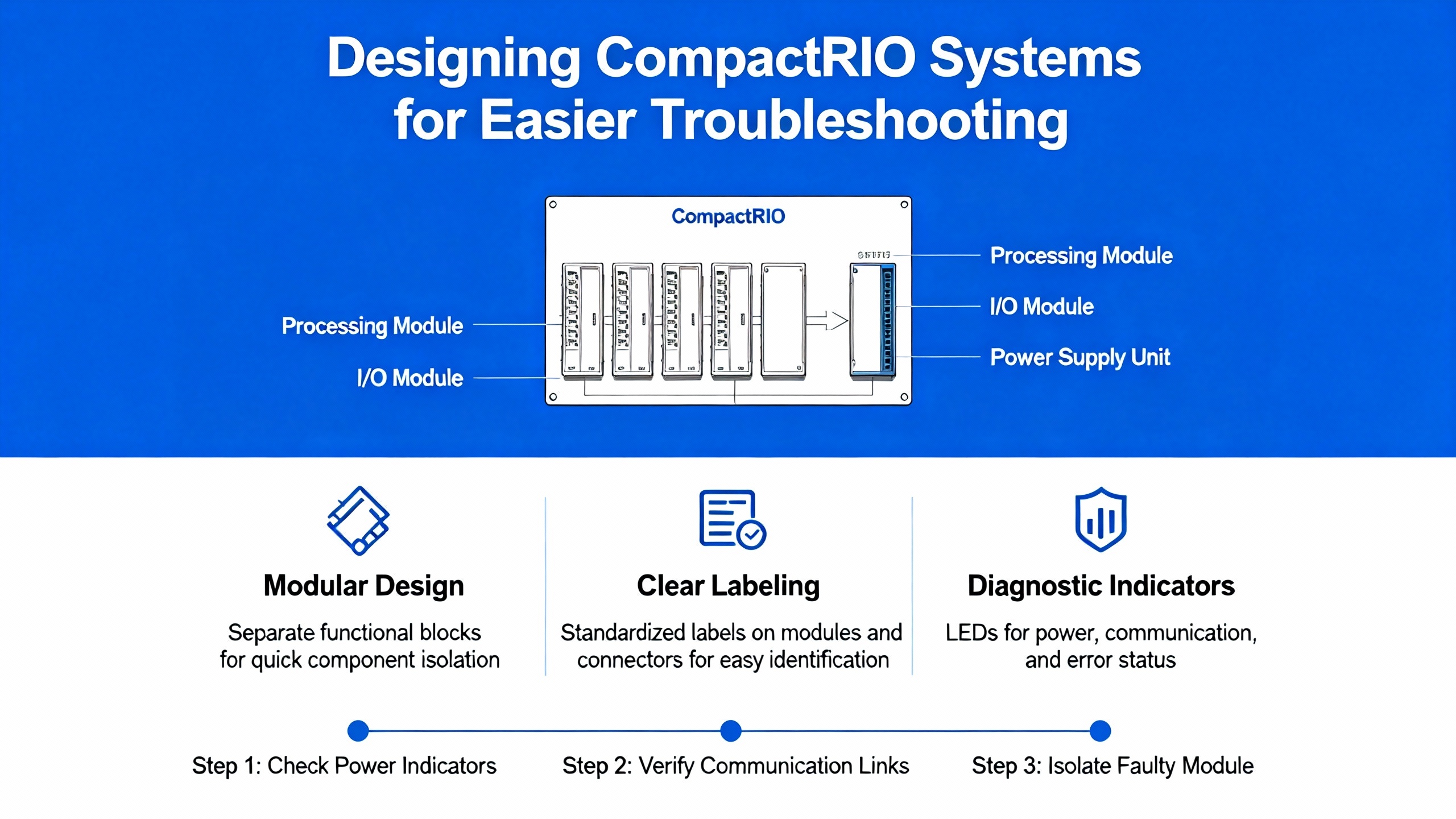

CompactRIO is a modular, realŌĆætime embedded control and data acquisition platform that combines a realŌĆætime CPU, an FPGA backplane, and C Series I/O modules in a single chassis. Operating instructions for systems such as the cRIOŌĆæ9075/9076 and cRIOŌĆæ9074 emphasize a few building blocks that matter directly to troubleshooting.

On the front panel, you typically have Power, Status, and User LEDs, an RJŌĆæ45 Ethernet port, a power connector, a Reset button, an RSŌĆæ232 port, and sometimes a USB port. At boot, the controller executes a powerŌĆæon selfŌĆætest, driving the Power and Status LEDs; the Status LED then turns off when the test passes. Those indicators, plus documented blink patterns in NI manuals, are your first window into basic health and boot state.

The chassis integrates a realŌĆætime controller and an FPGA backplane driving C Series I/O slots. NI documentation describes several startup options that you can set in Measurement & Automation Explorer (MAX), including Safe Mode, Console Out, IP Reset, No App, and No FPGA App. The Reset button can trigger a normal restart, or if held for roughly five seconds until the Status LED is solid yellow, it can boot the controller into Safe Mode. There is also a separate set of options in the NIŌĆæRIO Device Setup utility governing whether the FPGA bitfile autoloads on powerŌĆæup or reboot.

All of this matters because many ŌĆ£mysteryŌĆØ problems are simply the controller starting in a different mode than the one the team expects. You cannot troubleshoot a missing application or FPGA behavior if the startup options are disabling them.

Mechanically, NI operating instructions highlight that thermal and enclosure assumptions are part of the design, not an afterthought. A horizontally mounted CompactRIO on a flat, vertical metallic surface can typically run in ambient temperatures up to about 131┬░F, but other orientations or mounting surfaces reduce that limit and can affect module accuracy. To keep airflow and cabling clear, NI recommends at least 1 in of clearance above and below the chassis and about 2 in in front of the modules, with ambient measured a couple of inches away from the chassis in a defined location. In hazardous locations, some CompactRIO models carry Class I, Division 2 and Zone 2 approvals, but only when installed inside an enclosure rated at least IP54. Deviating from those conditions can push the hardware outside the validated envelope and manifest as intermittent faults that are very hard to reproduce in the lab.

Grounding is nonŌĆænegotiable. NI manuals require the chassis ground screw to be tied to earth ground using 14 AWG wire, and shielded cabling with plastic I/O connectors should have its shield bonded back to chassis ground with short 16 AWG conductors. In noisy industrial environments, one of my earliest checks for ŌĆ£randomŌĆØ analog noise or intermittent communication errors is always the ground path and shield termination.

Having this mental model of power, startup modes, mechanical limits, and grounding gives you a framework. When the system misbehaves, you know which layer you are actually testing: power and environment, realŌĆætime OS, FPGA, or field I/O.

A very common field complaint is, ŌĆ£The cRIO does not appear in NI MAX,ŌĆØ or ŌĆ£It shows up as disconnected.ŌĆØ NIŌĆÖs own knowledge base and CompactRIO documentation offer a series of concrete checks that are worth treating as a standard playbook.

NI support articles start with fundamentals: confirm that the CompactRIO is powered correctly according to its user manual. That means an external DC supply sized for the controller plus all installed C Series modules, wired with the positive lead to the V terminal and the negative lead to the C terminal of the power connector. The power connector must not be inserted or removed while energized, and the chassis provides only a single layer of reverseŌĆævoltage protection. If the Power LED is not solid and the Status LED never enters a normal boot pattern, you have a power or hardware problem long before you worry about IP addresses.

Once power is stable, look at the Ethernet port. The link and activity LEDs should light or blink when connected to a live port. If they do not, swap in a known good shielded twistedŌĆæpair cable rated for Ethernet, try a different switch port, or connect directly to a PC with an appropriate cable. NI documents emphasize that the maximum cable length is roughly 328 ft; beyond that, troubleshooting should include the physical network infrastructure, not just the controller.

On engineering laptops and desktops with multiple network adapters, device discovery can be derailed by routing ambiguity. NIŌĆÖs troubleshooting guidance suggests disabling all network adapters except the primary wired NIC when hunting for a CompactRIO. That includes turning off WiŌĆæFi during discovery. The goal is to eliminate competing gateways and subnets that can prevent the NI tools from finding a device that is otherwise broadcasting normally.

When using a laptop directly with a CompactRIO, NI recommends connecting both through an Ethernet router instead of relying only on a direct cable. With a router providing DHCP, both the PC and the controller can land in the same subnet with valid addresses, which often makes discovery and configuration far more straightforward than juggling linkŌĆælocal addresses.

NI notes that on first powerŌĆæup, a CompactRIO controller attempts to obtain an address via DHCP. If that fails, it falls back to a linkŌĆælocal address in the 169.254.x.x range. In a production network, you should not assume that a linkŌĆælocal address is reachable from your engineering workstation, especially if the plantŌĆÖs switches and routers enforce strict VLAN and routing rules.

Coordinate with the network administrator to confirm that there is a functional DHCP server on the relevant subnet and that the switch port is enabled and not blocking the deviceŌĆÖs traffic. NI specifically warns that some IT security or management tools may block what they consider invalid addresses, such as 0.0.0.0, which certain controllers can use briefly when resetting IP configuration. A practical pattern is to connect the CompactRIO to a known DHCP network first to obtain a valid address, and only then adjust its static IP and firewall rules according to plant standards.

Even with correct wiring and addressing, NI MAX can still fail to list the controller due to its own configuration. In MAX, under Tools ┬╗ NIŌĆæRIO Settings, NI suggests adding a wildcard entry (ŌĆ£*ŌĆØ) under Remote Device Access to allow all remote systems to access RIO devices. Without that, you might be unintentionally limiting discovery to a narrow set of IP ranges.

Firewalls also matter. NIŌĆÖs documentation for NI System Configuration 15.0 notes that on Windows XP and Windows 7 you must explicitly allow the ŌĆ£Measurement & AutomationŌĆØ program through the Windows firewall so that MAX can discover and communicate with NI devices. On tightly lockedŌĆædown corporate images, I have seen this single checkbox make the difference between ŌĆ£no CompactRIOs foundŌĆØ and ŌĆ£everything shows up immediately.ŌĆØ

Starting with NI System Configuration 15.0, NI introduced a ŌĆ£Remote System Discovery Troubleshooter.ŌĆØ After installing the latest System Configuration runtime, you can rightŌĆæclick Remote Systems in MAX, invoke this troubleshooter, and follow a guided diagnostic that checks common discovery conditions and proposes next steps. It is not magic, but it codifies many of the checks that field engineers used to do manually.

If the CompactRIO can be discovered and accessed from another computer, but not from your current host, and you have already verified that the latest drivers are installed, NI suggests considering a reimage or clean reinstall of the development computer. That is a last resort, but in some cases corrupted host software is genuinely the root cause.

Another documented scenario is that MAX lists the CompactRIO under Remote Systems, but its status is ŌĆ£disconnected.ŌĆØ NIŌĆÖs official guidance in such cases is to reset the NI MAX configuration database and, if necessary, reformat the realŌĆætime controller. Reformatting clears potentially corrupted configuration on the target at the cost of reinstalling the software stack, so it must be planned and documented carefully. Before taking that step, back up any deployed realŌĆætime applications and FPGA bitfiles, along with critical configuration such as aliases and I/O mappings.

A discussion on the LAVA (LabVIEW Advanced Virtual Architects) community describes a CompactRIO suffering ŌĆ£complete lockup with no memory leaks.ŌĆØ The device became entirely unresponsive and required a reboot, yet RAM usage did not point to a classic memoryŌĆæleak scenario. That pattern will feel familiar to many engineers who work with embedded realŌĆætime systems.

In realŌĆætime and embedded environments, a hard lockup without obvious RAM exhaustion often hints at other culprits: CPU saturation, driver or I/O deadlocks, priority inversions, or even firmware or hardware faults. The LAVA discussion points toward a set of generic best practices that are worth applying systematically.

Continuous logging of CPU load, RAM usage, and I/O activity is not just a niceŌĆætoŌĆæhave; it is often the only way to see what happened in the seconds leading up to a lockup. The recommendation is to enable detailed system logs, monitor realŌĆætime loop timing, and capture that data persistently so you can reconstruct behavior right before the failure.

From a practical standpoint, that means building your applications with instrumentation hooks from day one. When I design realŌĆætime control loops on CompactRIO, I always include logging of loop period and any timing overruns, plus coarse CPU usage trending. If a controller later locks up on the plant floor, I have actual timeŌĆæstamped evidence instead of guesswork about whether CPU starvation preceded the event.

NIŌĆÖs CompactRIO knownŌĆæissues bulletins call out a specific scheduling problem on cRIOŌĆæ904x targets. When you configure CPU pools using the RT Set CPU Pool VI at boot, or before running your tasks, a highŌĆæpriority task can cause normalŌĆæpriority tasks to hang until that highŌĆæpriority task stops. NIŌĆÖs recommended workaround is either to set the CPU pool only after the highŌĆæpriority tasks are running, or, if you must set pools on boot, to ensure that normalŌĆæpriority tasks start before the highŌĆæpriority workload.

That issue illustrates both the power and the risk of CPU pools. In principle, they let you partition CPU cores so timeŌĆæcritical loops are isolated from less critical tasks. In practice, misconfiguration can hide entire sections of your application behind a scheduling corner case. If you are troubleshooting unexplained hangs on a cRIOŌĆæ904x, and your design uses CPU pools, crossŌĆæcheck your configuration against NIŌĆÖs guidance before diving into exotic theories.

The LAVA discussion also reinforces a longŌĆæstanding practice in embedded control: use a watchdog. That can be a software watchdog task running at high priority or an external hardware watchdog that expects heartbeats from the controller. When the watchdog stops seeing valid heartbeats, it resets or powerŌĆæcycles the CompactRIO.

A watchdog does not fix the root cause of the lockup, but it prevents the worstŌĆæcase outcome: a hung controller driving actuators indefinitely. For production systems, it is standard practice to combine internal software monitoring with an external hardware watchdog, especially when human safety or expensive equipment is at stake.

NIŌĆÖs LabVIEW FPGA developer material emphasizes that FPGA compilation is a multiŌĆæstage process that can take hours for intricate designs. FPGA resource utilization and numerical precision both affect the ability to meet timing constraints. Inadequate numerical precision is treated as a functional error, not just a performance quirk, and the number of bits allocated to integer and fractional parts directly affects both correctness and resource usage.

On top of that general complexity, NIŌĆÖs CompactRIO knownŌĆæissues documents identify several hardwareŌĆæspecific compilation failures that can look like random build breakage if you do not know what you are looking at.

For cRIOŌĆæ905x targets, NI documents that placing an NI 9205 module in slot 5 can cause LabVIEW FPGA compilations to fail intermittently, especially when the topŌĆælevel FPGA clock is set to 80 MHz. NIŌĆÖs recommended mitigation is to retry compilation or move the NI 9205 to a different slot in the chassis.

On cRIOŌĆæ904x targets, configurations with more than five NIŌĆæ9202 modules have been reported to fail FPGA compilation with synthesis messages indicating that the design needs RAM resources that exceed device capacity. NIŌĆÖs guidance is to update to LabVIEW 2018 and CompactRIO Device Drivers 18.0 or higher, where this specific limitation is addressed.

For CompactRIO singleŌĆæboard controllers that support NIŌĆæDAQmx and RealŌĆæTime Scan Resources, NIŌĆÖs 2022 Q3 knownŌĆæissues list notes that bitfiles are likely to fail compilation due to timing violations under LabVIEW 2022 Q3. The recommendation is to use LabVIEW 2021 or earlier for those targets until the issue has a resolved version.

There is also a set of sbRIO timing issues rooted in how the sbRIO CLIP Generator creates constraints. For sbRIOŌĆæ9651, sbRIOŌĆæ9607, and sbRIOŌĆæ9627, the generator does not place constraints for imported clocks into the XDC file, so Single Cycle Timed Loops driven by those clocks can vary in frequency. For timeŌĆæcritical FPGA designs, that is effectively an integrity failure. When troubleshooting strange jitter or nonŌĆædeterministic behavior in FPGA loops using imported clocks on those boards, it is important to check the constraints, not just the LabVIEW diagram.

Locale settings can even block configuration tools. NI notes that adding a CLIP on an sbRIO from a Windows machine that uses a comma as the decimal symbol can fail with a declaration error. Their workarounds are straightforward: change the decimal symbol in the Windows locale to a period or set a configuration flag in the LabVIEW initialization file to ignore the localeŌĆÖs decimal point. If CLIP configuration fails mysteriously on an internationalized engineering workstation, this is worth checking before assuming that the CLIP definition itself is invalid.

From a productivity standpoint, NIŌĆÖs LabVIEW FPGA guidance highlights that a local compile server on the development PC is suitable for small VIs but becomes a bottleneck as projects grow. Offloading to a dedicated network compile server can reduce compile times, with LinuxŌĆæbased servers tending to be faster than comparable Windows machines. For larger teams or for projects where cloud services are not an option, the LabVIEW FPGA Compile Farm Toolkit allows you to build an inŌĆæhouse compile farm, with a central server distributing jobs to multiple workers. NI also offers a cloud compile service that runs on highŌĆæend Linux infrastructure.

The practical troubleshooting connection is simple: if your team is spending more time waiting for compiles than debugging actual logic, introducing a compile farm or cloud compile can turn what feels like chronic ŌĆ£build instabilityŌĆØ into a normal development cycle. It does not fix design errors, but it does shorten the feedback loop, which is often the bottleneck when solving FPGAŌĆærelated issues on CompactRIO.

Some CompactRIO problems do not show up until you start switching module modes or interacting with RealŌĆæTime Scan resources. NIŌĆÖs knownŌĆæissues lists document several subtle behaviors that are easy to misinterpret as sensor or wiring faults.

NI reports that if a module is in use and you switch it from Scan Mode (also referenced as RealŌĆæTime Scan or RSI mode) to FPGA or NIŌĆæDAQmx mode, the module will output corrupted data for one scan before generating error ŌłÆ65536. The recommended practice is to ignore data from the single scan immediately preceding that error. In other words, your application should treat that transition as a discontinuity and avoid using that last scanŌĆÖs values in any control or logging logic.

This is a small detail, but if you are feeding those readings into alarms or trending databases, failing to handle that one corrupt scan can create confusing spikes or false events.

For modules that have not yet been deployed in RealŌĆæTime Scan mode, attempts to access their properties can return error 65704 with a message indicating that the RSI module URL could not be resolved. NIŌĆÖs guidance is straightforward: deploy the modules before attempting to access their properties.

In practice, this means that if your code programmatically queries module properties at startup, you must ensure that deployment has occurred, either manually or as part of the project deployment process, before those property nodes execute. Otherwise you will see intermittent propertyŌĆæaccess failures that disappear once someone manually deploys the chassis.

NIŌĆÖs bug documentation for the NI 9213 thermocouple module in an NI 9149 Ethernet chassis highlights a subtle error handling issue. When Open Thermocouple Detection is enabled and you read with a ŌĆ£Read Variable with TimeoutŌĆØ style interface, an open thermocouple might produce error codes ŌłÆ1950678943 or ŌłÆ1950679035 instead of the expected ŌłÆ65582, and the module may sample at the timeout rate.

NI suggests two mitigations. One is to move the NI 9213 to a different chassis if that is available. The other is to turn off Open Thermocouple Detection and implement openŌĆæcircuit detection manually in your application by recognizing the characteristic openŌĆæcircuit value produced by the module. If your plant has a pattern of intermittent thermocouple faults on NI 9213 modules in NI 9149 chassis, comparing your symptoms to this known issue can save significant time.

Beyond pure hardware and I/O behavior, the software stack itself can introduce problems if you treat it casually. NI maintains extensive knownŌĆæissues articles for CompactRIO device drivers and CompactRIO releases across years. A 2025 Q1 knownŌĆæissues summary, for example, consolidates longŌĆælived issues across NIŌĆæDAQmx, NIŌĆæRIO, CompactRIO versions from 16.0 onward, and related modules, some of which remained unresolved as of late 2024.

For CompactRIO targets with NIŌĆæDAQmx support, NI documents that uninstalling and then reinstalling the recommended software stack can corrupt module aliases and chassis aliases. The result is warnings in Measurement & Automation Explorer when you view those items. Instead of uninstalling, NI recommends reformatting the target and then reinstalling the software. From a troubleshooting standpoint, that means you should treat ŌĆ£remove some packages from the targetŌĆØ as a last resort and prefer a clean reformat plus reinstall when configuration changes are significant.

On Linux RealŌĆæTime CompactRIO controllers, NI notes that MAX technical reports no longer include the nirio.ini file. That file defines the RIO ServerŌĆÖs remote machine access list. If you have customized remote access permissions, and you rely on MAX technical reports to archive configuration, you will not capture those settings unless you manually retrieve nirio.ini from its directory on the target. When diagnosing remote access or security issues, it is important to know that this critical configuration file is not present in the standard report.

Several known issues relate to LabVIEW project tools and how they interact with CompactRIO targets. NI reports that in certain cases, using the Project & System Comparison dialog and changing a single CompactRIO channel action to ŌĆ£UploadŌĆØ can cause all module and channel actions to switch to ŌĆ£Upload.ŌĆØ NI recommends verifying module settings directly in the LabVIEW project and using the ŌĆ£Deploy AllŌĆØ command from the target rather than relying on fineŌĆægrained upload changes after comparisons.

Another documented issue is that when you copy a VI from one realŌĆætime controller target to another in a LabVIEW project and then attempt to run that VI, it may still attempt to execute on the original controller. Whether that succeeds depends on the VI and hardware configuration. NI lists no workaround. In a multiŌĆætarget project, this can create real confusion during commissioning. As a troubleshooting habit, when I bring up a project on site, I always confirm for each critical VI which target it is actually bound to before running anything.

NIŌĆÖs 2025 Q1 and later knownŌĆæissues documentation notes that NIŌĆæRIO and NI CompactRIO devices may fail under Linux kernels that enable DMA remapping, also known as IOMMUŌĆæbased DMA address translation. Kernel logs can show DMAR ŌĆ£DMA Read NO_PASIDŌĆØ faults and messages that page table entries lack read access. NI specifically calls out modern environments such as Ubuntu 22.04 with kernel versions 6.8 and higher and Ubuntu 24.04 as affected.

If you are troubleshooting flaky or nonŌĆæfunctional NIŌĆæRIO devices on such Linux hosts, this is a key clue. The practical options are to validate the configuration thoroughly, potentially disable DMA remapping, or select alternative kernel configurations that avoid the issue when working with NIŌĆæRIO hardware.

For SingleŌĆæBoard RIO devices, NI documents that upgrading to runmode 22.5 can make the devices unresponsive over USB. The recovery procedure is to hold the reset button to boot into Safe Mode, which runs an earlier stack (for example, 21.0.0), and then downgrade the controller back to a LabVIEW 2021 software stack. If a previously responsive sbRIO suddenly disappears from the USB view after a runmode update, this known issue provides a direct path back.

Several published case studies illustrate not only what CompactRIO can do, but also how system architecture can make troubleshooting easier.

In a case study from Amfax, an advanced 3D PCB assembly inspection system relies on CompactRIO as the central product management and control platform. The a3Di system uses twin metrology to take millions of 3D measurements with accuracy finer than 0.0002 in, assesses solder joints against IPC Class 1, 2, and 3 recommendations, and controls motors, optical sensors, SMEMA interfaces, pneumatics, and safety signals via CompactRIO and NI 9375D I/O. Because the control platform is tightly integrated and deterministic, Amfax was able to eliminate false calls and remove manual inspection operators. From a troubleshooting perspective, that kind of design makes it much clearer where issues live: in the dimensional measurement algorithms, in the field devices, or in the deterministic controller at the center.

A Viewpoint Systems case study on powerŌĆægeneration condition monitoring shows CompactRIO used as the edge device for flux probe and blade tip timing applications. The CompactRIO FPGA performs highŌĆæspeed data acquisition and frontŌĆæend preprocessing, such as tip location detection, while the realŌĆætime processor handles higherŌĆælevel timing analysis. A master PC provides the operator user interface, longŌĆæterm data collation, and reporting. To respect CompactRIOŌĆÖs finite bandwidth and CPU resources, the designers deliberately send full raw waveform snapshots only occasionally, relying mostly on reduced data such as detected tip locations. This separation of concerns makes troubleshooting more tractable: if timing analysis looks wrong, you can check whether the FPGAŌĆælevel tip detection is correct before blaming higherŌĆælevel code or the UI.

In an educational setting, a ResearchGate paper describes a CompactRIOŌĆæbased platform for teaching PID control on a closedŌĆæloop DC motor speed system. Students adjust proportional, integral, and derivative parameters and observe how the motorŌĆÖs dynamic response changes, including poor behavior when gains are badly tuned. Even though that environment is academic, it echoes a key industrial lesson: realŌĆætime control performance must be validated under realistic conditions, not assumed from theory.

A Viewpoint case on obsolescence management describes replacing legacy discrete logic and wireŌĆæwrap boards with a combination of PXIe and CompactRIO hardware. Because documentation for the old system was unreliable, the team adopted a ŌĆ£trust but verifyŌĆØ approach, capturing real I/O behavior with logic analyzers, oscilloscopes, and DMMs while running standard checkout procedures. They then mapped that verified behavior into a CompactRIOŌĆæbased design, using custom interposer boards to adapt existing harnesses. This approach, while timeŌĆæintensive, pays dividends when troubleshooting: you know exactly how the new system is supposed to behave relative to the old one.

Across these examples, a few design themes emerge that make future troubleshooting easier. Architect systems so CompactRIO handles deterministic I/O and preprocessing, while higherŌĆælevel PCs deal with visualization and reporting. Minimize unnecessary data transfers to avoid saturating bandwidth. Build rich logging and observability directly into realŌĆætime applications. And where CompactRIO is replacing legacy equipment, validate actual signals rather than relying solely on old drawings.

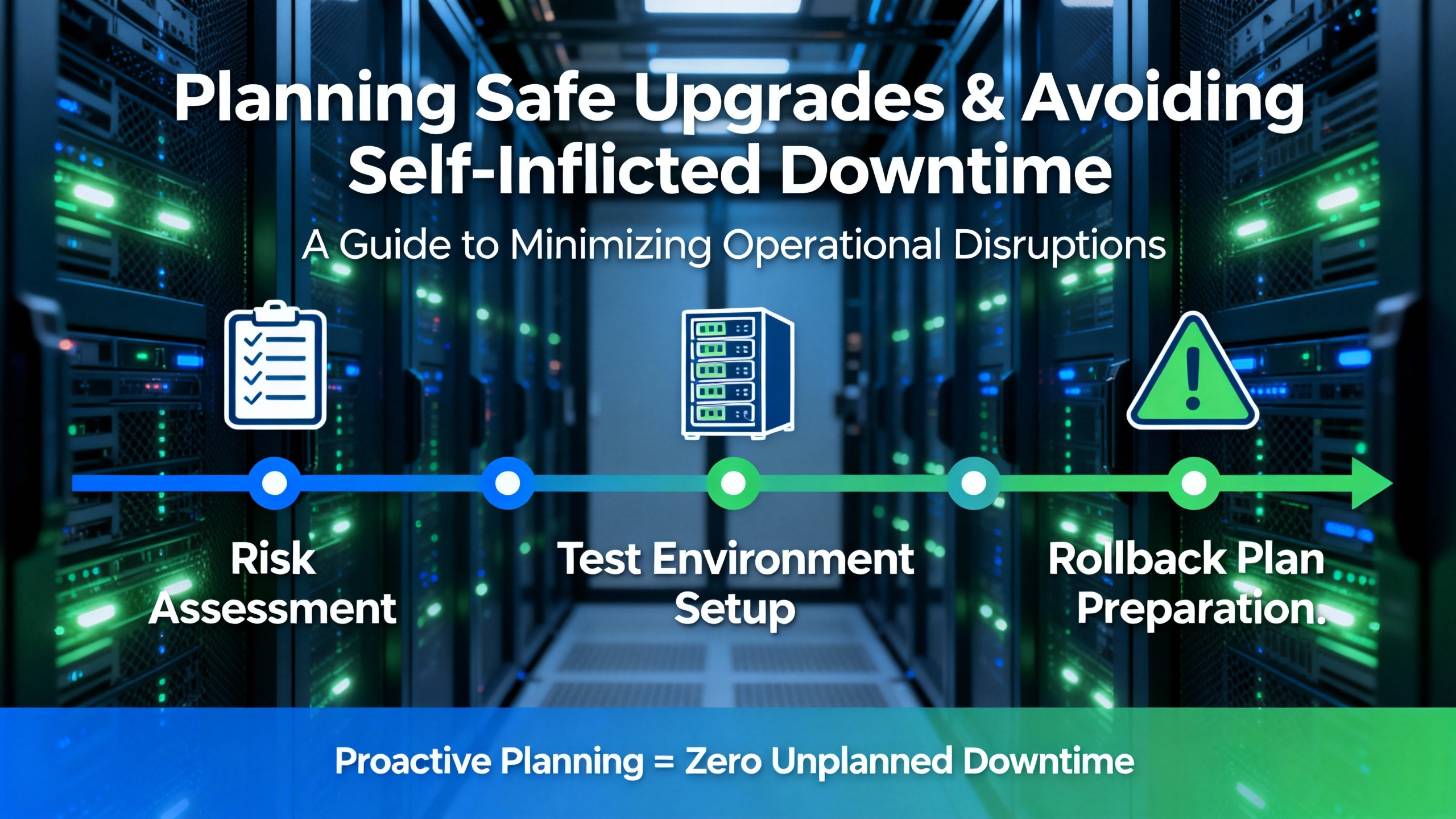

One of the research notes references a nowŌĆæunavailable article whose title focused on preventing costly mistakes when updating industrial monitoring hardware. Even without that specific text, common industry practice and NIŌĆÖs own experience with compatibility issues point toward a few concrete patterns.

Before upgrading CompactRIO software stacks or swapping hardware, verify compatibility between LabVIEW versions, CompactRIO drivers, NIŌĆæDAQmx versions, and any thirdŌĆæparty libraries. NIŌĆÖs knownŌĆæissues pages often mention that certain problems are only avoided when you pair, for example, LabVIEW 2018 with CompactRIO Device Drivers 18.0, or when you avoid particular combinations such as CompactRIO 2022 Q3 with certain sbRIO targets. Reading those bulletins in advance is cheap insurance.

Test changes in a nonŌĆæproduction or pilot environment whenever possible. That can be a benchŌĆætop controller with similar modules or a spare chassis configured to mirror the line. NIŌĆÖs documentation around longŌĆælived issues across releases is a reminder that regressions can persist over multiple years; you do not want to discover those during a live maintenance window.

Prepare a rollback plan before you touch a running system. In CompactRIO terms, that means having backups of realŌĆætime applications, FPGA bitfiles, configuration aliases, and a knownŌĆægood software stack that you can reinstall if a new version shows unexpected behavior. For highŌĆæconsequence systems, I also recommend documenting the exact versions of LabVIEW, NIŌĆæRIO, and driver stacks that are known to work and treating that as a controlled baseline.

Document existing configurations and wiring clearly, including module order, terminal assignments, and any nonŌĆædefault startup options such as Safe Mode, Console Out, or No FPGA App. Train maintenance and operations staff on what a normal CompactRIO powerŌĆæup looks like, how to interpret frontŌĆæpanel LEDs, and how to use NI MAX safely. Schedule upgrades during planned downtime windows where the business can tolerate a rollback if something goes wrong. NIŌĆÖs experience with issues like alias corruption after uninstall/reinstall, sbRIO runmode regressions, and Linux DMA remapping limitations all reinforce the same lesson: changes to the software and host environment can have farŌĆæreaching side effects on CompactRIO behavior.

The following table summarizes several recurring CompactRIO troubleshooting scenarios documented in NI support and knownŌĆæissues material, along with the associated context.

| Symptom or Behavior | Target / Context | NIŌĆæDocumented Cause or Guidance |

|---|---|---|

| NormalŌĆæpriority tasks hang while a highŌĆæpriority task runs | cRIOŌĆæ904x with CPU pools configured at boot | CPU pools set via RT Set CPU Pool VI at boot can starve normalŌĆæpriority tasks; set pools after starting tasks or start normalŌĆæpriority tasks first. |

| FPGA compilation fails intermittently with NI 9205 in slot 5 | cRIOŌĆæ905x, topŌĆælevel FPGA clock near 80 MHz | Module placement and clocking combination triggers occasional compile failures; retry or move NI 9205 to a different slot. |

| FPGA compilation fails with RAM resource error for NIŌĆæ9202 count | cRIOŌĆæ904x with more than five NIŌĆæ9202 modules | Synthesis reports insufficient RAM resources; upgrading to LabVIEW 2018 and CompactRIO Device Drivers 18.0 or later is recommended. |

| One scan of corrupted data before error ŌłÆ65536 on mode switch | CompactRIO modules switched from Scan to FPGA/DAQmx | Mode switching while module is in use corrupts one scan; explicitly ignore data from the scan immediately preceding the error. |

| Module property access returns error 65704 | Modules not deployed under RealŌĆæTime Scan resources | Accessing properties for undeployed RSI modules fails; deploy modules before reading properties. |

| NI 9213 returns unexpected error codes on open thermocouples | NI 9213 modules in NI 9149 Ethernet chassis | Open Thermocouple Detection can report different error codes and alter sampling; move module or disable hardware detection and handle open circuits in software. |

| sbRIO Single Cycle Timed Loop timing is erratic | sbRIOŌĆæ9651, ŌĆæ9607, ŌĆæ9627 with imported clocks | sbRIO CLIP Generator omits clock constraints, causing inconsistent loop periods; review clock constraints and design accordingly. |

| NIŌĆæRIO devices fail on certain Linux kernels with DMAR faults | Linux hosts with DMA remapping enabled | IOMMUŌĆærelated limitations cause DMA read faults; deployments on specific kernels (such as newer Ubuntu releases) require validation or configuration changes. |

In practice, when I run into one of these patterns on site, the fastest path forward is often to search NIŌĆÖs knownŌĆæissues documentation for the exact error code, hardware family, and software version combination. That is usually enough to distinguish between ŌĆ£our code is wrongŌĆØ and ŌĆ£we are running into a documented platform limitation.ŌĆØ

I start with power and physical connectivity, confirming that the Power LED shows a healthy state and that the Ethernet link and activity LEDs are active with a known good cable and switch port. Then I simplify the host network configuration by disabling extra adapters and WiŌĆæFi, confirm DHCP and subnet configuration with the network team, and only after that do I dive into NI MAX settings such as Remote Device Access wildcards and firewall exceptions for Measurement & Automation. If another PC can see the same controller, I also compare driver versions and, as a last resort, consider reimaging the development machine.

If a symptom is tightly tied to a particular hardware model, slot, module combination, or software version, I always crossŌĆæcheck NIŌĆÖs CompactRIO knownŌĆæissues bulletins. Examples include compilation failures only when a module is in a specific slot, task hangs that appear only on certain cRIOŌĆæ904x configurations with CPU pools, or sbRIO timing anomalies that match documented CLIP generator limitations. When the symptom aligns closely with an NIŌĆædocumented issue, it is often more efficient to apply the recommended workaround or version change than to spend days searching for a bug in application logic that is not there.

Yes. NI documentation and community experience both emphasize watchdogs as a standard robustness tool. Software health checks are valuable for catching logical failures and handling graceful recovery, but they can fail in the same scenarios that freeze your application. An external hardware watchdog that can independently reset or powerŌĆæcycle the CompactRIO when heartbeats stop provides a second line of defense and limits the duration of any lockup, which is critical in industrial automation and protection systems.

In the field, keeping CompactRIOŌĆæbased systems trustworthy is less about clever tricks and more about disciplined habits: verify the basics first, instrument everything that matters, study NIŌĆÖs knownŌĆæissues bulletins before you upgrade, and design architectures that make it obvious where problems live. When you apply that mindset, CompactRIO becomes what it is meant to be on your line or in your lab: a rugged, deterministic workhorse that does its job quietly in the background while you focus on the process it is there to protect.

Leave Your Comment