-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for ŌĆ£ŌĆØ.

When you spend your days on factory floors and in electrical rooms, you stop thinking of ŌĆ£powerŌĆØ as a simple on/off condition. It is a chain of vulnerable links: incoming utility, switchgear, transfer switches, breakers, UPS systems, PLC power supplies, and hundreds of seemingly ordinary components that quietly keep everything alive. When any one of those links fails during a storm, a wildfireŌĆærelated blackout, or a grid disturbance, you do not just lose lights. You risk downtime, product loss, safety incidents, and in some facilities, lifeŌĆæsafety systems going dark.

The U.S. Energy Information Administration has reported that nearly all electrical customers experience at least one outage per year, with typical events lasting more than an hour. Other research points out that outages and grid instability are trending in the wrong direction, driven by extreme weather and aging infrastructure. In that environment, an emergency electrical components supplier is not a ŌĆ£nice to have.ŌĆØ It is a strategic partner that keeps your power and control systems recoverable when the grid or your own equipment lets you down.

As an industrial automation engineer, I have been on calls where a single obsolete breaker or a failed generator battery has stopped a whole production line. The facilities that ride through those events with the least pain are the ones that have already built relationships with suppliers who know how to respond fast, source hardŌĆætoŌĆæfind parts safely, and support emergency power systems around the clock. This article breaks down how to think about emergency electrical components, how rapidŌĆæresponse suppliers operate, and what to look for when you choose one.

Before talking about suppliers, it is worth clarifying what ŌĆ£emergency powerŌĆØ actually covers. In code language, emergency power supply systems and the components that feed them are more structured than most people realize.

An emergency power supply system (EPSS), as described by NFPA 110, is the entire arrangement that delivers backup power when the primary utility fails. It includes the generator or other power source, the controls, switchgear, transfer switches, batteries, fuel system, and associated wiring. Within that EPSS, the emergency power supply (EPS) is the actual power source. Most commonly that means an engineŌĆægenerator set fueled by diesel, natural gas, propane, or gasoline, sized to pick up all loads designated as emergency or standby.

NFPA distinguishes between Level 1 and Level 2 systems. Level 1 systems are those where failure could result in loss of human life or serious injury. In practice, they feed loads such as emergency lighting, fire alarm systems, fire pumps, smoke control equipment, elevators dedicated to egress, and lifeŌĆæsustaining medical equipment. Level 2 systems support less critical functions like HVAC, ventilation, water treatment, and some industrial processes where power loss creates hazards or hampers rescue or firefighting, but is less immediately lifeŌĆæcritical.

Outside the code world, emergency power solutions for homes and small facilities are often grouped into a few practical categories, based on guidance from manufacturers and backupŌĆæpower specialists:

FuelŌĆæbased generators. Gasoline, diesel, or propane units produce power on demand. Propane and gas sets can supply high wattage and long run times if you can get fuel. They are the traditional answer for long, frequent outages or large loads but are noisy, produce exhaust, require outdoorŌĆæonly operation, and need regular maintenance.

BatteryŌĆæbased portable power stations. These are rechargeable battery packs with inverters and multiple output ports. They may be charged from wall outlets, vehicle outlets, or solar panels. Modern units highlighted by several manufacturers deliver from roughly 500 W up into the 1,500 to 3,000 W range, with batteries sized from a few hundred to several thousand wattŌĆæhours. They are quiet, safe to use indoors, and excellent for sensitive electronics.

Solar generators. When you pair a portable power station with properly sized solar panels, you get a ŌĆ£solar generatorŌĆØ that can recharge during daylight without fuel. Articles from solar providers describe systems in the three kilowatt range powering refrigerators, pumps, and other household loads for extended periods, as long as the panels receive enough sunlight.

Hybrid strategies. Some users deliberately combine a solar generator for everyday and shortŌĆæduration outages with a fuelŌĆæbased generator as a secondary backup for long emergencies or wholeŌĆæfacility support. This mirrors what we do in industry: multiple layers of backup, each suited to a different scenario.

From an automation standpoint, the takeaway is that emergency power is a system, not a single device. The supplier that will actually help you during a power crisis understands this system view and can support not only the generator, but also the transfer mechanism, distribution components, and the controls that sit on top of it.

When people think ŌĆ£emergency power,ŌĆØ they tend to picture a generator on a concrete pad. On real jobs, the failures I see most often are not the generator engine itself but the supporting electrical and control components. Typical trouble spots include automatic transfer switches that fail to transfer, breakers that trip and will not reset, contactors welded closed, corroded lugs in temporary power panels, and deeply ordinary items like power supplies for PLC racks.

Research into industrial sourcing shows that ŌĆ£hardŌĆætoŌĆæfind electrical partsŌĆØ often include obsolete components, legacy system parts, specialty items with limited production runs, and parts affected by global supply disruptions. United Industries reports that seventyŌĆæthree percent of industrial buyers experience delays due to component shortages and that obsolete parts alone can account for about forty percent of production downtime. In other words, the part that fails in an emergency is often the one you cannot buy quickly through normal channels.

The global electrical components market is projected by United Industries to exceed $600 billion by 2033, nearly doubling from current levels. Yet that huge market is fragmented. About sixtyŌĆæeight percent of industrial buyers reportedly use more than fifty different electrical suppliers, but only twentyŌĆæthree percent have realŌĆætime visibility into supplier inventory. That fragmentation is exactly why an emergency specialist supplier, who already curates inventory and relationships across many channels, becomes valuable when you are trying to restore power under time pressure.

From a plant perspective, the emergency components you will most often be scrambling for fall into a few groups.

Critical distribution components. These include moldedŌĆæcase and power breakers, fuses, switchboards, bus plugs, contactors, motor starters, and transfer switches. When a breaker fails mechanically or a transfer switch controller dies as a storm hits, your ability to bring power back safely depends on finding an equivalent or preŌĆæapproved alternative fast.

Emergency power system parts. These are generator controls, engine sensors, fuel system components, voltage regulators, governor cards, paralleling gear parts, and batteries. NFPA guidance calls for weekly and monthly inspection of Level 1 and Level 2 EPS and associated components, plus periodic load and conductance tests on batteries. When those tests reveal weak batteries or failing controls, you need replacements before storm season, not after.

Automation and control hardware. PLCs, remote I/O modules, industrial Ethernet switches, VFDs, and HMI panels are frequently on allocation or endŌĆæofŌĆælife. In emergencies, component sourcing specialists and independent distributors help fill the gap when standard channels cannot supply a legacy PLC power supply or a specific safety relay that is holding up a restart.

Temporary power gear. Cables, camŌĆælock connectors, portable distribution panels, portable transfer switches, and stepŌĆædown transformers are the plumbing between a rental generator and your facility. They fail mechanically, are sometimes misapplied, and often are not stocked in large quantities by general distributors.

An emergency electrical components supplier focused on rapid response will build inventory and sourcing capability around exactly these categories, with an eye toward the parts that tend to be scarce when major storms, wildfires, or geopolitical shocks ripple through the supply chain.

A power emergency is exactly when organizations are most tempted to buy from unfamiliar brokers or online sellers offering ŌĆ£in stockŌĆØ inventory at suspiciously low prices. Unfortunately, research on counterfeit electronic and electrical components shows that this is a dangerous reflex.

United Industries points to the global counterfeit electronics market as a serious safety and reliability threat, especially for obsolete components. Red flags include pricing far below market from unverified sources, missing or altered manufacturer markings and date codes, poor packaging with spelling errors or inconsistent branding, and unusual shipping origins outside authorized distribution regions. ERAI, a wellŌĆæknown industry watchdog, reported more than 1,055 suspect counterfeit or nonconforming parts in 2024, the highest level in nearly a decade.

Quality and authenticity programs recommended by multiple sources converge on similar themes. Buyers should prioritize suppliers with recognized certifications, such as ISO 9001 for quality management, AS9120 for aerospace and defense supply chains where applicable, and membership in organizations like ERAI that focus on counterfeit avoidance. They should demand documentation for components: certificates of compliance from the original manufacturer, test reports and inspection data from accredited labs, chainŌĆæofŌĆæcustody records that show handling history, and traceability back to manufacturing batches.

When we integrate those recommendations with what I see at industrial sites, the lesson is straightforward. During an outage, do not let urgency override quality discipline. Work only with emergency suppliers who can show you their counterfeitŌĆæavoidance procedures, documentation standards, and access to thirdŌĆæparty test labs. For highŌĆærisk components that feed lifeŌĆæsafety systems or critical production equipment, thirdŌĆæparty visual, XŌĆæray, and electrical testing before installation is a reasonable safeguard, not a luxury.

In theory, rapid response is just marketing language. In practice, for an industrial facility, it shows up as concrete behaviors.

The calls that go well typically start with a supplier who knows your site and critical loads before anything goes wrong. They have your singleŌĆæline diagrams on file, understand which panels feed lifeŌĆæsafety loads versus process loads, and know which breakers, relays, and PLC modules are truly singleŌĆæsource risks. That preparation is consistent with best practices on vendor risk profiling and disaster preparedness documented by organizations that study supply chain resilience.

When something fails, time is lost if a supplier has to ask basic questions about voltage, fault current, enclosure type, or shortŌĆæcircuit ratings. Good emergency suppliers work more like engineering partners. They verify the failed part, crossŌĆæreference acceptable equivalents, and confirm that any substitute preserves form, fit, and function.

Research on emergency component procurement in the semiconductor space, where matureŌĆænode MCUs, power ICs, and memory devices have seen severe shortages, shows how experienced emergency partners manage lead time and risk. They insist on realŌĆætime inventory proof, such as serialŌĆænumbered availableŌĆætoŌĆæpromise data and traceable lot codes, rather than vague claims of ŌĆ£in stock.ŌĆØ They are transparent about whether a part is coming from authorized channels, preŌĆævetted independents, or surplus inventories, and they pair that with rigorous inspection and testing.

For emergency generators, analysis from procurement specialists emphasizes that sourcing is a strategic activity, not an adŌĆæhoc rental decision. A buyŌĆæversusŌĆærent strategy depends on your outage patterns, critical load profile, and capital budget. Renting generators for seasonal or unpredictable needs reduces upfront spend and shifts maintenance responsibility to the rental provider, while permanently installed standby units offer automatic, longŌĆæduration support for sites that cannot tolerate extended downtime. In both cases, early planning matters. Procurement leaders are advised to collaborate with operations teams to define voltage, fuel type, emissions requirements, cabling, and switchgear needs, and to account for lead times and peakŌĆæseason constraints like hurricane or wildfire seasons.

On site, that planning shows up as preŌĆæengineered tieŌĆæin points, preŌĆæverified cable sets, and clear procedures. When a rental generator arrives, you want to roll it into place, land cables on known connectors, confirm proper phasing, run a brief load test, and then transition loads under controlled conditions. An emergency components supplier with both equipment and parts on hand can support that process far better than a generic rental yard.

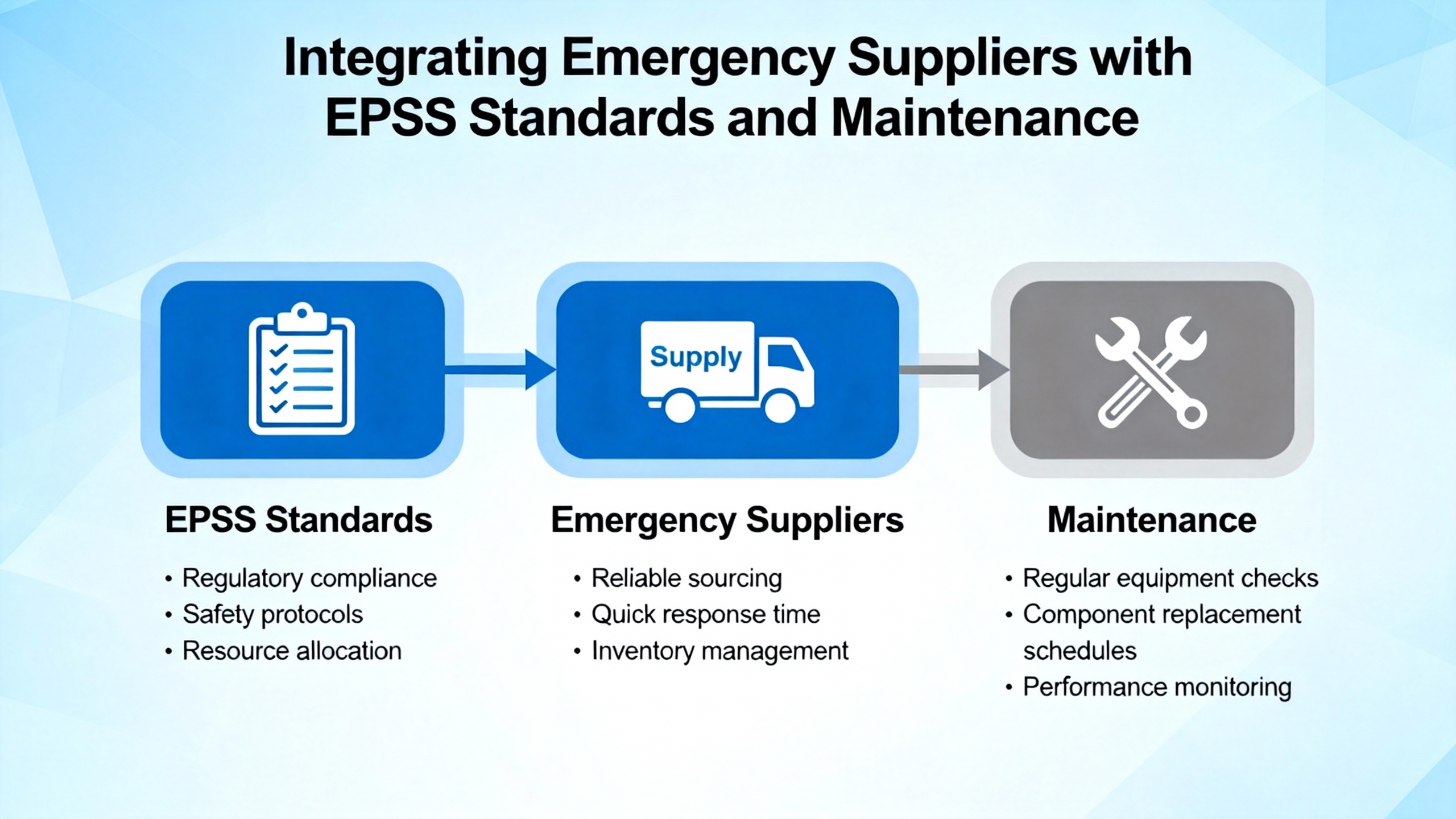

Rapid response is only half the story. The other half is whether the solution keeps you in compliance with safety standards and your own reliability goals.

NFPA 110 sets expectations for how EPSS equipment should be installed, operated, maintained, and tested. It calls for weekly inspection of Level 1 EPS components, monthly inspection for Level 2, monthly load exercises for both, and a more extended test of Level 1 systems at least once every thirtyŌĆæsix months for the duration of their assigned class, up to four hours. Those class ratings describe how long the system must be able to run without refueling. A Class 2 system is designed for two hours of operation, while a Class 48 must run for fortyŌĆæeight hours.

Inspection requirements drill down into details. Level 1 emergency power supplies and their batteries must be checked weekly for electrolyte level, voltage, and physical condition, with quarterly load tests and monthly records of electrolyte specific gravity or equivalent tests for nonŌĆæmaintainable batteries. Transfer switches and paralleling gear must be operated at least monthly to verify that they transition correctly between normal and emergency positions and back. Fuel quality should be tested at least annually.

From an engineering standpoint, those requirements matter because they drive your demand profile for emergency components. If you are following NFPA 110 properly, you will discover weak batteries, failing transfer switches, and marginal generators during routine tests, not during hurricanes. That means you will be buying replacement parts on a regular cadence, which in turn means your emergency supplier should be stocked and ready to support those planned interventions as well as unplanned failures.

A strong supplier understands NFPA expectations and can recommend components and maintenance strategies aligned with them. For example, they might suggest rotating through your generator fuel storage with annual quality testing, replacing suspect fuel and filters ahead of severeŌĆæweather seasons, and upgrading battery systems when repeated tests show declining performance. When you do bring in a rental generator or temporary switchgear, they should help ensure that it does not undermine the coordination and protection scheme your EPSS was originally designed around.

Traditional phoneŌĆæandŌĆæspreadsheet sourcing breaks down during crises. Several studies on electronic and electrical procurement stress how important digital tools are to maintaining both speed and control.

Online marketplaces and B2B platforms for components reportedly process tens of millions of part searches per day, with AI algorithms matching buyers to inventory in a matter of seconds. Companies that adopt these platforms are seeing sourcing cycle times cut significantly compared with manual phone and email methods. For electrical contractors and industrial buyers, digital procurement systems provide a single interface to track what is being bought, from whom, at what price, and how often, instead of scattering that data across emails and paper purchase orders.

Federal programs such as the Federal Energy Management Program encourage organizations to integrate energyŌĆæefficient product procurement into their purchasing processes. They provide tools to search for energyŌĆæefficient products, sample contract language that embeds efficiency requirements, and guidance on lowŌĆæstandbyŌĆæpower equipment. While those resources are targeted at federal agencies, the underlying idea applies to any facility: when you are replacing electrical components or specifying emergency power equipment, you should favor products that are both reliable and energyŌĆæefficient where possible.

A highŌĆæperforming emergency electrical components supplier will lean into these digital and efficiency trends. They will offer online catalogs with realŌĆætime stock visibility, integrate with your procurement system or ERP, and tag products that meet recognized efficiency or environmental standards. On the analytics side, they will use demand forecasting tools and market intelligence to stock safety inventory of components that are prone to long lead times or shortage cycles, reducing your risk of being caught without key parts.

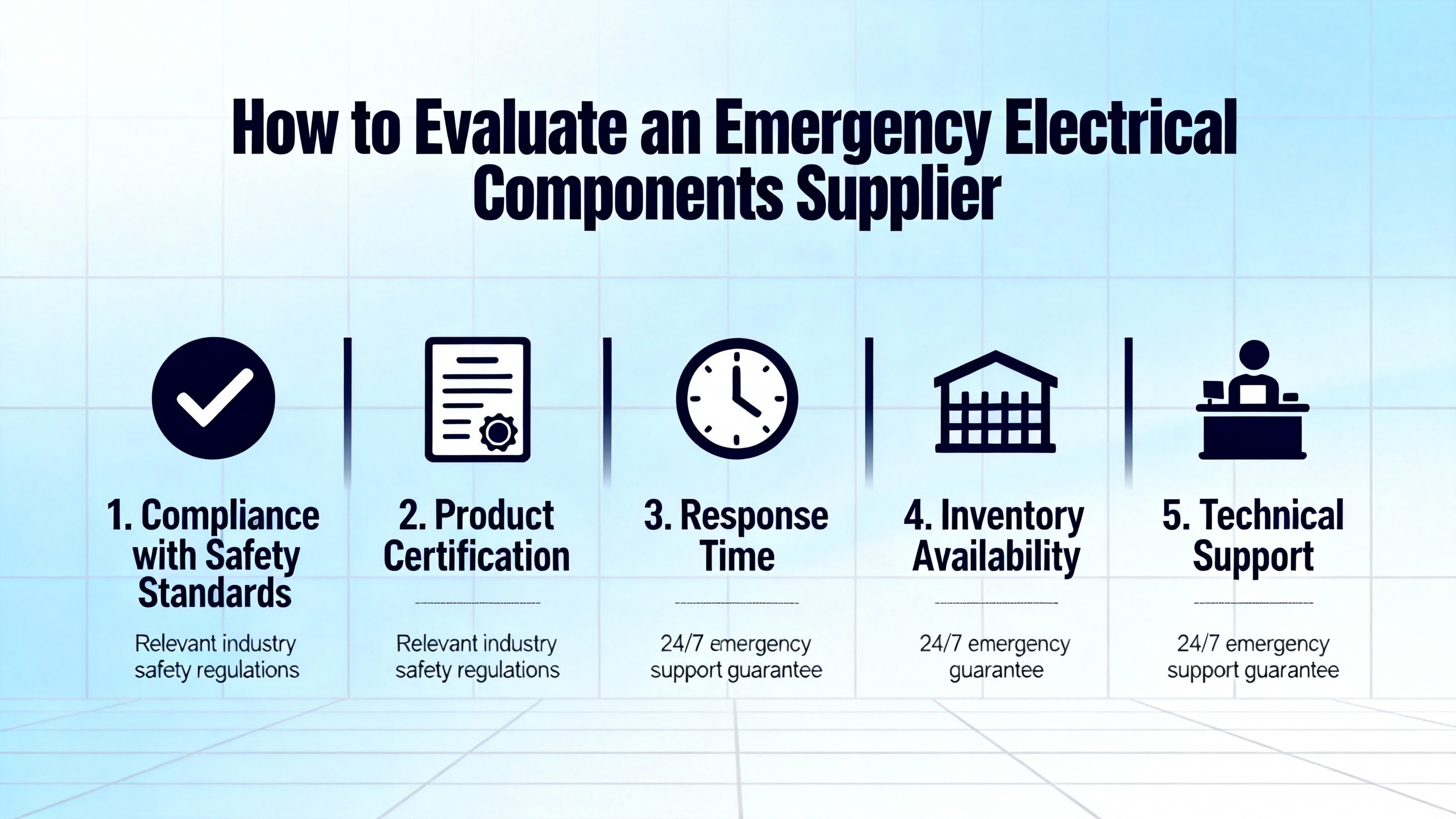

Choosing an emergency supplier is not about who has the flashiest website. The research on industrial sourcing, electrical contractor supply, and riskŌĆæmanagement strategies points to several attributes worth scrutinizing.

Availability and leadŌĆætime performance are foundational. Look for evidence that the supplier tracks and reports their onŌĆætime delivery performance, particularly during past events like hurricane seasons or regional wildfire blackouts. Suppliers that maintain multiŌĆæchannel sourcingŌĆöcombining authorized distributors, independent surplus suppliers, certified brokers, and OEMŌĆædirect relationshipsŌĆötend to be more resilient, as long as they maintain quality discipline. Several guides recommend maintaining at least three channel types per critical component category.

Quality and compliance practices should be visible, not hidden behind marketing claims. Ask how the supplier ensures that all electrical equipment complies with the National Electrical Code and is certified by Nationally Recognized Testing Laboratories where required. For electronic and electrical components, ask which quality certifications they hold themselves and which they require from their upstream suppliers. Confirm whether they are part of counterfeitŌĆæmonitoring organizations and what their inspection protocols look like, especially for surplus or used equipment.

Technical capability separates parts shops from true emergency partners. A good supplier for industrial automation and power work will have engineers or application specialists who can discuss faultŌĆæcurrent ratings, selective coordination, generator sizing and derating, transfer schemes, and component substitution at the level your plant engineers expect. They should be comfortable referencing standards like NFPA 110, NFPA 70, NFPA 70B, and the Life Safety Code and understand how changes in components can ripple into arcŌĆæflash studies, coordination curves, and PLC program behavior.

Digital tools and communication style matter more than most teams admit. Suppliers that provide online portals, API integrations, and realŌĆætime order tracking remove a lot of friction, particularly when you are trying to manage multiple work sites or coordinate with contractors. They should be able to share clean documentation packagesŌĆödatasheets, certificates, test reportsŌĆöin one place, rather than forcing you to chase them down via email every time.

Finally, consider their approach to pricing and total cost of ownership. Guides on electrical procurement emphasize that the lowest upfront price is often a trap if it comes at the cost of lower quality, higher energy consumption, or unreliable delivery. The best emergency suppliers will help you compare not only part prices but also the lifetime operating and risk costs associated with different options, whether you are choosing between generator types, breaker technologies, or alternative components for an obsolete control module.

A simple way to organize your evaluation is to think in terms of how a supplier helps you across four dimensions: uptime, safety, compliance, and operating cost. The table below frames this concept.

| Evaluation Dimension | What the Supplier Should Contribute | Why It Matters During Power Issues |

|---|---|---|

| Uptime | Fast access to critical components, temporary power equipment, and knowledgeable support staff who understand your systems | Reduces duration of outages and keeps production or critical services running |

| Safety | Components that meet appropriate codes and standards, plus guidance aligned with NFPA and NEC requirements | Prevents fire, shock, and lifeŌĆæsafety hazards during abnormal conditions |

| Compliance | Documentation, traceability, and testing practices that satisfy regulators and internal auditors | Avoids legal penalties and ensures your EPSS and electrical systems pass inspections |

| Operating Cost | Advice that balances capital, fuel, maintenance, and efficiency when selecting equipment | Controls lifecycle cost instead of chasing shortŌĆæterm savings that backfire later |

No supplier, no matter how good, can compensate for a facility that has no plan. Agencies like FEMA and CISA, along with supplyŌĆæchain specialists, repeatedly stress the need for documented disaster preparedness and resilient power strategies.

At a minimum, every industrial site or large commercial facility should have an upŌĆætoŌĆædate, written plan that covers lossŌĆæofŌĆæpower scenarios. In practice, this involves identifying critical loads, mapping which switchgear and feeders supply them, and classifying which loads must be maintained for life safety, environmental protection, and business continuity. On the automation side, it means identifying which PLCs, HMIs, and communication networks must stay online and how they behave if power is lost unexpectedly.

That analysis should feed directly into your sourcing strategy. For every critical electrical component that has a long lead time, is at risk of obsolescence, or is unique to a legacy system, you should know in advance where you can get it. United Industries recommends proactive obsolescence management: monitoring product lifecycles, planning lastŌĆætime buys for atŌĆærisk components, qualifying alternatives while the original parts are still available, and using resale or exchange channels to manage excess inventory.

SupplyŌĆæchain experts also call for vendor risk profiles that track each supplierŌĆÖs status, shipment history, and exposure to risks such as severe weather, geopolitical events, or cyberattacks. Enterprise resource planning systems and integrated procurement platforms help build that picture, giving you visibility into inventory and shipments across the network and enabling faster reconfiguration when something breaks.

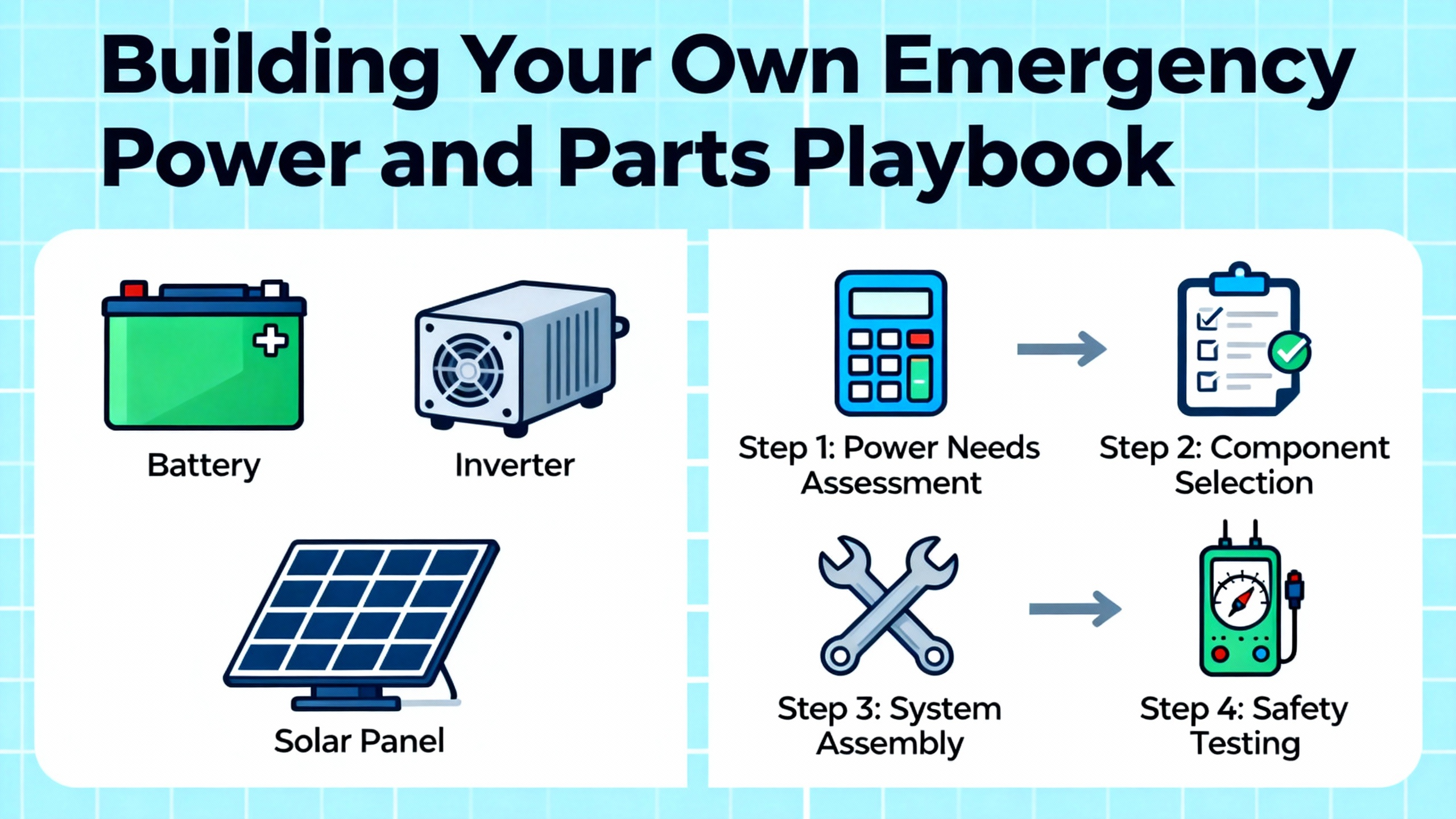

In practice, a healthy emergency playbook has both technical and procurement components. On the technical side, it defines how you will safely connect temporary generators, when you will shed loads, how you will protect sensitive equipment, and how you will test your EPSS. On the procurement side, it identifies the emergency suppliers you will call for components and power equipment, the contractual frameworks in place, and the decision rules for when to rent versus when to buy.

Facilities that practice that playbookŌĆöthrough tabletop exercises or actual drillsŌĆöare invariably more composed when the outage hits. They know which breakers to open, which contractors and suppliers to call, and how long they can sustain critical loads on their current configuration. That level of preparation turns emergency suppliers into true partners instead of lastŌĆæminute saviors.

Q: What is the difference between an emergency electrical components supplier and a generator rental company? A: A generator rental company focuses on providing temporary power sources, usually engineŌĆægenerator sets and associated fuel services. An emergency electrical components supplier may arrange rentals but also stocks and sources the supporting components required to restore and safely distribute power: breakers, contactors, transfer switches, cabling, temporary distribution panels, control modules, and more. For industrial and commercial facilities, restoring power safely often depends as much on those components as on the generator itself.

Q: Are batteryŌĆæbased portable power stations useful in industrial settings, or are they just for homes and camping? A: BatteryŌĆæbased power stations, especially higherŌĆæcapacity units in the 1,500 to 3,000 watt range described by several manufacturers, are very effective for supporting control systems, instrumentation, networking gear, and service tools in industrial environments. They are clean, quiet, indoorŌĆæsafe, and well suited to sensitive electronics. They are not a replacement for large standby generators feeding heavy motors or whole plants, but they are excellent for keeping PLCs, HMIs, laptops, and communication gear alive during maintenance or localized outages.

Q: How often should we review our emergency sourcing and power plan with suppliers? A: A practical cadence is to revisit the plan at least annually, and additionally before seasons with known risk in your region, such as hurricane or wildfire seasons. Many standards call for annual or multiŌĆæyear testing of EPSS performance; coupling supplier and sourcing reviews with those milestones works well. The review should cover criticalŌĆæparts lists, obsolescence status, supplier performance metrics, and any changes in your load profile or regulatory obligations.

Q: Should we standardize on fewer component brands to make emergency sourcing easier, or diversify to reduce risk? A: Research on sourcing and risk points to a balance. Standardizing on a limited set of vendors and product families simplifies maintenance, training, and stocking, but relying on a single brand or source for critical components increases vulnerability when that line goes on allocation or reaches end of life. A robust strategy standardizes where practical but also qualifies alternate components and maintains multiŌĆæchannel sourcing for the most critical parts. An experienced emergency electrical components supplier can help you design your bill of materials to preserve that balance.

When power problems hit, there is no substitute for a solid EPSS, disciplined maintenance, and a calm operations team. But in my experience, the difference between a bad day and a disaster often comes down to how quickly you can get the right electrical components and temporary power equipment on site. Investing time now to select the right emergency electrical components supplier, align on standards and documentation, and build a joint playbook is one of the most practical steps you can take to keep your plant, building, or campus running when the grid does not.

Leave Your Comment