-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for ŌĆ£ŌĆØ.

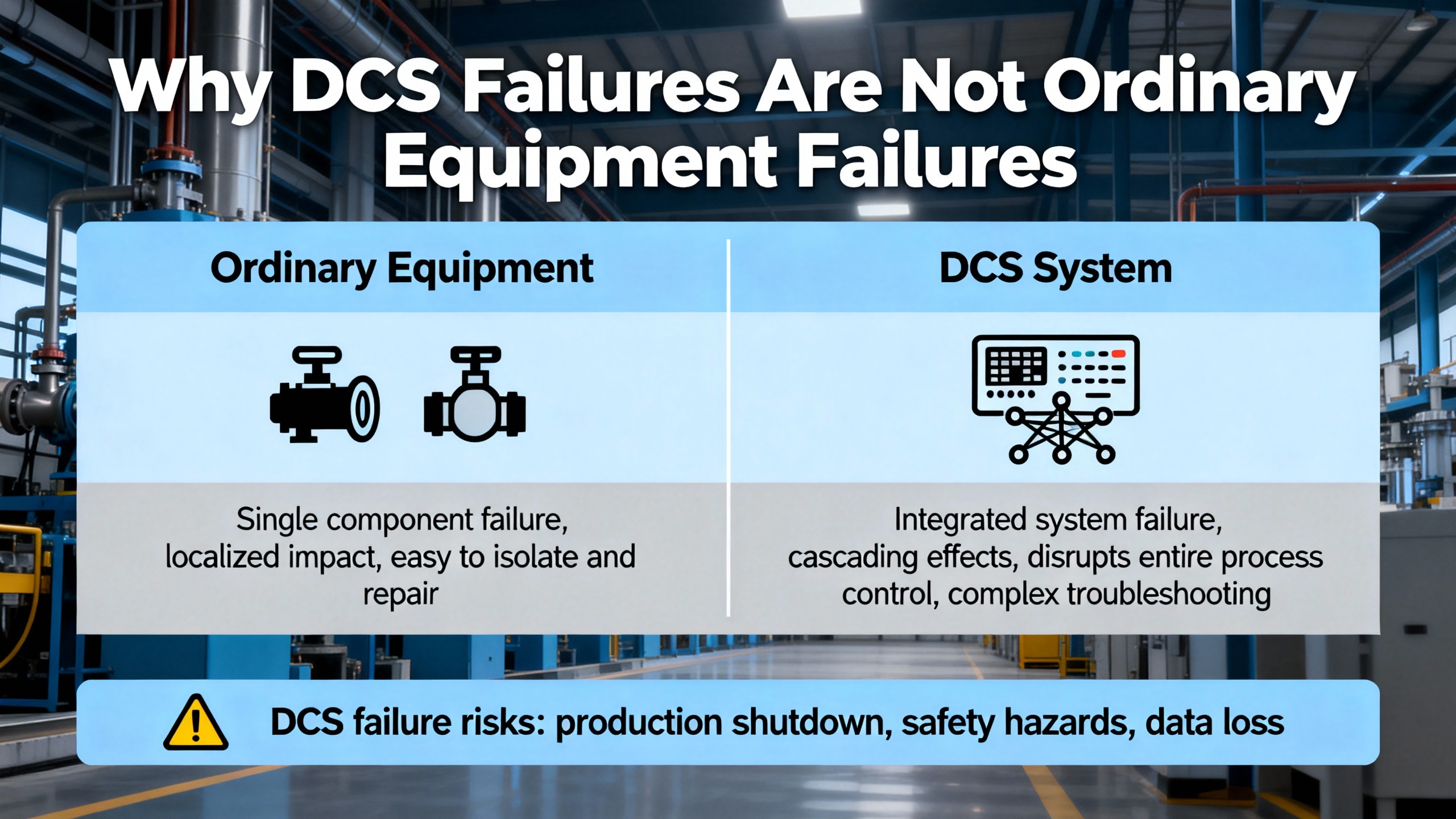

In most process plants I walk into, the distributed control system is treated like the air: essential, always assumed to be there, and only noticed when something goes wrong. When a DCS controller or network switch fails and you discover the last spare was quietly used six months ago, the result is not a theoretical inconvenience. It is a shutdown, operators standing idle, raw material going to waste, and production management asking why a few thousand dollarsŌĆÖ worth of parts just cost them several hundred thousand dollars in lost output.

Emergency inventory management for DCS spare parts is about making sure that moment never happens, even when supply chains are disrupted, warehouses are flooded, or key vendors are offline. Research on justŌĆæinŌĆæcase inventory from Cyzerg, emergency inventory management insights from Zenventory, and MRO and emergency preparedness guidance from Grainger and OSHA all point in the same direction: in highŌĆæconsequence operations, resiliency matters more than shaving the last bit of carrying cost.

This article looks at DCS spare parts through that lens. I will connect what we know from inventory optimization, disaster logistics, and OT cybersecurity to a practical, plantŌĆælevel approach: how to know what you have, decide what must be on the shelf ŌĆ£just in case,ŌĆØ and integrate those decisions into your emergency playbooks so you can keep the plant safe and running when it matters most.

A Distributed Control System, as described by automation providers such as LLumin and MaintenanceCare, is an architecture where control is spread across multiple controllers and smart devices, all supervised from a central control room. Field sensors and actuators feed local or programmable logic controllers, which execute control algorithms. These controllers communicate over industrial networks to operator workstations and engineering stations, where operators visualize trends, acknowledge alarms, and adjust setpoints in real time.

LLumin explains that DCS architectures are typically hierarchical. Field devices sit at the base, above them are I/O and smart devices, then supervisory computers, production control systems, and finally higherŌĆælevel planning and scheduling systems. MaintenanceCare emphasizes that this distributed approach improves performance, allows parallel processing, and avoids single points of failure compared to a single centralized computer.

In practice, those distributed components still have very real single points: individual CPUs, I/O racks, communication modules, servers, and network switches. Losing the wrong module at the wrong time can halt an entire production line, and in industries like chemicals, oil and gas, or power generation, it can also compromise safety and environmental protection.

When control is lost, plants rely on independent safety systems, failŌĆæsafe designs, and trained operators. LLumin and MaintenanceCare both stress that reliable control and continuous monitoring are a core part of safe operation. At the same time, the US Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) points out that operational technology failures can have financial, environmental, health, and safety impacts when industrial control systems are disrupted.

GraingerŌĆÖs work on MRO inventory makes the point clearly from another angle: maintenance, repair, and operations items may be expensive to hold, but stockŌĆæouts that trigger downtime are often even more costly. Their analysis, citing IBM, notes that good inventory optimization and predictive tools can cut unplanned downtime related to parts by up to half and reduce maintenance budgets significantly. Zenventory highlights the same pattern in emergency logistics: lack of critical supplies during a crisis quickly translates into higher casualties and property loss.

For a DCS, that means spare parts are not simply a cost line in the warehouse. They are an engineered barrier that prevents an OT failure from becoming a safety event, a regulatory violation, or a multiŌĆæday outage. Treating them like generic inventory, optimized only for carrying cost, is a mistake.

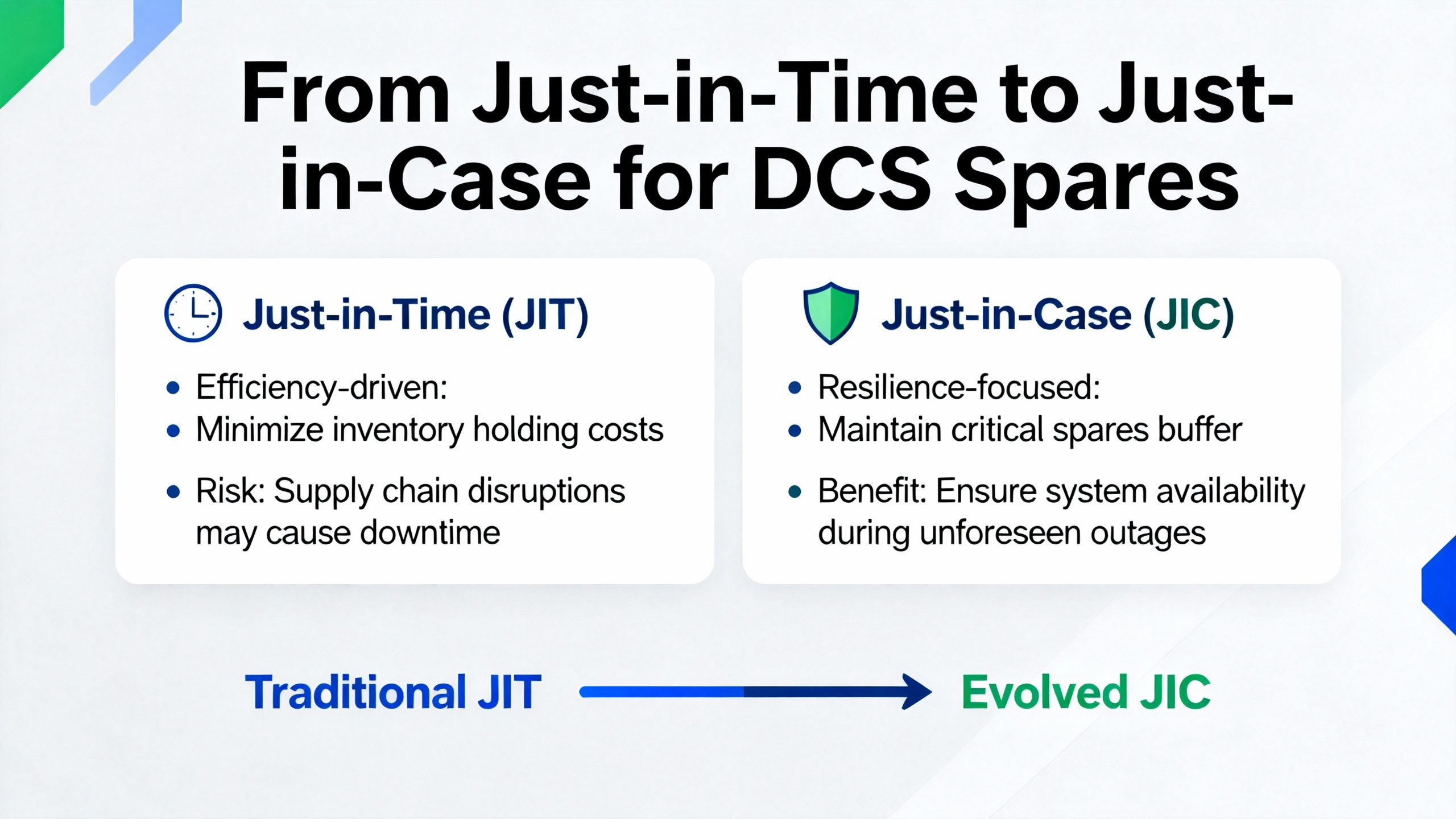

Cyzerg contrasts justŌĆæinŌĆætime (JIT) and justŌĆæinŌĆæcase (JIC) inventory as two opposite philosophies. JIT minimizes onŌĆæhand stock and relies on tightly coordinated suppliers so inventory arrives exactly when needed for production. JIC, in contrast, accepts higher inventory and carrying costs in exchange for a resilient buffer that absorbs disruptions in demand or supply.

In a packaging warehouse or retail channel, JIT can be attractive. Demand is predictable and the downside of a short stockŌĆæout is lost sales and extra shipping. For DCS components, the calculus is different. DCS parts are often specialized, sometimes from a single vendor, sometimes with long production or import lead times. RELEX Solutions highlights how long lead times erode a companyŌĆÖs ability to meet demand, push organizations toward higher safety stocks, and tie up capital. When you combine that with high criticality, the balance moves away from pure JIT.

The two approaches in a DCS context can be summarized as follows.

| Inventory approach | Description in controlŌĆæsystem context | Pros for DCS spares | Cons for DCS spares |

|---|---|---|---|

| JustŌĆæinŌĆætime (JIT) | Minimal spares on site; rely on fast supplier response and accurate demand forecasts. | Lower carrying costs and less capital tied up in shelves of electronics. | Very vulnerable to supplier delays, long lead times, and crises; stockŌĆæouts can cause long outages or unsafe conditions. |

| JustŌĆæinŌĆæcase (JIC) | Deliberately hold surplus spares for critical components as a safety buffer. | High resilience to disruptions, better ability to weather crises, fewer emergency expedites. | Higher storage, insurance, and obsolescence costs; capital locked in shelves. |

Cyzerg notes that JIC is specifically designed to mitigate the risk of stockouts, production interruptions, and customer service disruptions. When you view your ŌĆ£customerŌĆØ as the production line and safety as a primary requirement, the argument for JIC on key DCS parts becomes straightforward.

Emergency inventory research from Zenventory defines emergency inventory management as ensuring essential resources are available, visible, and quickly deployable during disasters to minimize operational disruption and loss of life. Elmasys, in its review of crisis inventory management, explains that disasters can occur at any time, with severely limited and delayed information on demand and supply. A review on disaster relief supply management published in a medical research archive goes further and observes that disaster relief is roughly eighty percent logistics, emphasizing how coordination, prepositioning, and inventory decisions dominate outcomes.

For a DCS, that means certain classes of parts should be treated as emergency inventory, not ordinary stock. Controllers that run entire process units, communication gateways that tie remote substations back to the control room, and network switches that host safetyŌĆærelated traffic are not items you wait on during a hurricane, regional power outage, or global supply chain disruption. They are parts you preposition and protect.

In other words, JIC is not a blanket strategy, but for the truly critical DCS modules the decision is not whether to hold any spares. The decision is how many, where, and under what governance.

CISAŌĆÖs guidance on OT asset inventory is blunt: if you do not know what you have, you cannot protect it. An OT asset inventory is an organized and regularly updated list of OT systems, hardware, and software. CISA recommends capturing attributes such as manufacturer, model, operating system, communication protocols, IP and MAC addresses, criticality, location, and even logging status and user accounts, then organizing them into a taxonomy based on function and criticality.

In DCS terms, that inventory should tell you which controllers are installed in each cabinet, their firmware levels, which I/O cards they use, how they connect to the safety system and PLCs, and where the operator and engineering workstations sit in the network. It should also capture which equipment resides in which physical areas or zones, following the ISA/IEC 62443 concept of logical or physical zones and the conduits that connect them.

This is the foundation for spareŌĆæparts planning. Without a trustworthy OT inventory, I have seen plants order expensive spares they can never use because the installed system is a different vintage, or fail to notice that a supposedly standard controller type has several variants that are not interchangeable.

Once you have an inventory, you can classify components by criticality. LLumin and MaintenanceCare describe typical DCS components: distributed controllers, smart I/O modules, humanŌĆōmachine interfaces, engineering workstations, servers, smart field devices, and the underlying networks that tie everything together. CISA suggests classifying OT assets either by criticality or function to support riskŌĆæbased decisions.

For spareŌĆæparts planning, it is useful to map those components into a simple criticalityŌĆæbased view.

| DCS asset class | Example components | Typical failure impact | Emergency stocking approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core controllers | Main DCS CPUs controlling process units, integrated safety controllers when applicable | Loss of control over a unit; potential trips, quality issues, or safety risk depending on design. | Treat as highestŌĆæcriticality emergency inventory; hold dedicated spares with JIC philosophy. |

| I/O and marshalling | Analog and digital input/output cards, remote I/O, marshalling interfaces | Loss of signals or actuators for groups of field devices; may disable loops or interlocks. | Stock sufficient spares to replace at least one or two full racks per critical area, factoring in common failure history. |

| Control networks | DCS switches, routers, firewalls, media converters for control and safety networks | Loss of communication between controllers, HMIs, historians, or safety systems. | Hold compatible spares for each network tier and preconfigure them where possible. |

| Servers and workstations | Engineering stations, operator HMIs, application and historian servers | Loss of visibility, trending, engineering access, or data logging; in some designs, loss of control. | Maintain spare workstations and rapid rebuild images; consider JIC for unique server hardware. |

| Smart field devices | Critical transmitters, positioners, smart valves on highŌĆæhazard services | Loss of key measurements or actuators that may force shutdowns. | Use criticalityŌĆæbased stocking similar to MRO: emergency inventory for lifeŌĆæsafety and highŌĆæconsequence points. |

| Power and support | Power supplies, UPS modules, cabinet climate control components | Loss of power or overheating for DCS cabinets and network racks. | Stock spares aligned with historical failure rates and impact on plantŌĆæwide control. |

This table is an example, not a universal template. The important point is to connect each class of asset to its real impact and to decide where emergency inventory is warranted. That decision should be synchronized with your OT risk analyses, process hazard reviews, and safety instrumented function design.

SBN Software frames emergency supply management as a strategic imperative grounded in risk assessment. They recommend evaluating the specific scenarios your location and industry face, then defining the equipment, supplies, and procedures you need. Elmasys echoes this idea for crises: organizations should have a formal crisis inventory plan specifying how inventory is assessed, which products are prioritized, and how communication with suppliers and customers is handled.

For DCS, riskŌĆæbased planning starts with understanding your worst credible scenarios. These range from the mundane, such as a controller failure or network card burnout, to broader events like a warehouse fire, storm damage, or regional disruption of logistics. Scanco, in its work on warehouse disaster recovery, stresses identifying natural and manmade hazards, mapping how they affect operations and supply chains, and planning mitigation measures and backup resources.

Link those scenario insights back to your DCS inventory. Which components are singleŌĆævendor, longŌĆælead items that become impossible to obtain quickly if that vendorŌĆÖs factory is shut down or shipping lanes are disrupted? Which modules, if lost, force you into manual operation or shutdown for extended periods? Those are the parts that move to the top of the emergency inventory list.

Inventory optimization guidance from EasyReplenish emphasizes that optimization is about service levels: keeping the right products in the right quantity, location, and time while minimizing costs. It contrasts proactive optimization with reactive management that only responds to shortages after they occur.

In a DCS context, you can express service levels as timeŌĆætoŌĆærecover metrics. For example, you might decide that a failed controller for a critical unit must be replaceable and commissioned within a few hours, while a historian server can be down for a longer period without unacceptable impact. That choice drives how many spares you hold, where you hold them, and how you train your staff to use them.

The key is to make these targets explicit and to align them with production, safety, and corporate risk appetite. Without that alignment, procurement will naturally push toward minimizing stock, while operations and safety quietly build unofficial ŌĆ£hidden inventory,ŌĆØ exactly the kind of behavior Grainger warns about when they describe technicians stashing parts to protect themselves from stockŌĆæouts.

Zenventory underlines the importance of knowing where emergency stock is and being able to deploy it quickly. For hospitals and other timeŌĆæcritical environments, they stress realŌĆætime visibility of supplies across locations, along with efficient transfers when demand surges.

The same principle applies to DCS spare parts. You may choose to hold certain spares in a central warehouse, others in a secure cabinet inside the control room, and still others at a corporate or regional hub. That decision should be driven by access time during an incident, the risk profile of each location, and the likelihood of a single event taking out both the primary equipment and its spares.

Ownership also matters. CISAŌĆÖs governance guidance for OT asset inventory recommends defining roles, responsibilities, and scope. Someone must own the DCS spareŌĆæparts program across locations, and local teams must understand which items they can use, which must be escalated, and how to replenish after use. Without that clarity, spares drift, disappear, and slowly lose their emergency value.

RELEX Solutions highlights several structural causes of long lead times: inaccurate forecasting, supplierŌĆæside disruptions, and internal inefficiencies. They note that when lead times are long, organizations tend to hold more safety stock, which raises holding costs but may be necessary to preserve service levels. They also recommend planning proactively for major holidays and shutdowns at international suppliers and cultivating alternative suppliers to reduce dependency.

For DCS spares, alternate suppliers are often not an option for core components, but the logic still applies. Know which items are vulnerable to long lead times or vendorŌĆæspecific shocks. For those parts, justŌĆæinŌĆæcase stocking is not a luxury. It is your only realistic way to guarantee availability during a crisis.

Supplier relationships become part of your emergency planning as well. SBN Software argues for contracts that explicitly address crisis situations, including expedited shipping, allocation guarantees, and pricing arrangements. While that is more common in general emergency supplies, the same idea can be built into framework agreements or lifecycle support contracts with DCS vendors and integrators.

LLumin describes how integrating DCS with CMMS tools allows remote health monitoring, predictive diagnostics, and structured planning and scheduling of maintenance. MaintenanceCare similarly emphasizes that DCS systems benefit from preventive maintenance and asset tracking. Grainger observes that MRO demand is highly variable, especially during emergencies, and that historical usage data is often unreliable because parts get moved, hidden, or misrecorded.

Rather than running a standalone DCS spareŌĆæparts cabinet that no one outside OT understands, it is usually more effective to integrate those spares into your broader MRO and assetŌĆæmanagement program. Use your CMMS or assetŌĆæmanagement software to record DCS modules as stocked items, track their movements, and associate them with work orders and failure codes. Predictive modeling and variabilityŌĆæaware planning, as Grainger describes, can then help you refine stocking levels based on true usage rather than guesswork.

Done well, this integration takes advantage of the documented benefits of inventory optimization that Grainger and IBM highlight: reductions in unplanned downtime related to parts, lower inventory costs, and significant savings in maintenance budgets, all while maintaining or improving service levels.

OSHAŌĆÖs guidance on workplace emergencies and evacuations explains that employers should have written emergency action plans describing how to report emergencies, evacuate, account for personnel, and coordinate rescue and medical duties. Designed Conveyor Systems extends this to warehouse and distribution environments, recommending formal emergency action plans for fires, medical emergencies, severe weather, hazardous material spills, and security issues, with clear chains of responsibility and regular training and drills. ScancoŌĆÖs disasterŌĆærecovery advice for warehouses confirms that planning, testing, and program improvement over time are critical to surviving major incidents that close a quarter of businesses permanently.

For DCS spare parts, this means they cannot sit outside those plans. Your emergency action plan should specify who is authorized to work on DCS hardware during a crisis, where critical spares are located, how they will be protected in events such as flooding or fire, and how restoration of control systems is prioritized relative to other recovery actions. If power must be restored, structural safety confirmed, and hazardous materials secured before technicians enter certain areas, your DCS recovery procedures and spareŌĆæparts deployment must be sequenced accordingly.

An article titled ŌĆ£Emergency Handling of DCS Failures in Process IndustriesŌĆØ underscores the importance of having explicit procedures for DCS failure events, even though its body is not available here. Combining that title with the general emergency planning principles from OSHA and Designed Conveyor Systems leads to a clear conclusion: you need structured, trained, and tested response procedures for DCS failures.

Those procedures should cover detection and diagnosis, determining whether redundancy or failover functions can keep the process safe, deciding when to switch to manual or local control, retrieving and installing the appropriate spare modules, validating operation, and documenting the event. They should also define who leads the technical response, who communicates with operations and management, and how decisions are made when information is incomplete, as Elmasys notes is common in crises.

The point is not to script every scenario. It is to prevent improvisation under pressure, especially when you are replacing critical control equipment using emergency inventory. In my experience, plants that wait until the first major outage to decide who can pull a controller out of the spare cabinet and who can modify configuration are setting themselves up for longer downtime and higher risk.

Zenventory advocates strongly for technology in emergency inventory: realŌĆætime tracking of stock levels and locations, multiŌĆælocation visibility, and mobile access so teams can locate and deploy supplies quickly. They also emphasize methods such as FirstŌĆæExpiring, FirstŌĆæOut rotation for perishable items and safety stock to buffer against unexpected disruptions. In healthcare environments, DCS (the healthcare integrator, not the control system) shows how RFID tags, barcode scanners, and assetŌĆæmanagement software automate tracking of critical assets, extend asset life, and prevent waste.

SBN and CISA both describe barcode and RFIDŌĆæbased tracking as enablers of accurate, upŌĆætoŌĆædate inventories. Applying those concepts to DCS spares, you can tag each module, controller, and network device, scan it into and out of secured cabinets, and link that information to your CMMS records. That gives you the realŌĆætime visibility Zenventory calls for and mitigates the hidden inventory problem Grainger highlights.

For items with genuine shelf life, such as batteries in UPS modules or certain consumables that support DCS infrastructure, FEFO rotation, as recommended by Zenventory for emergency supplies, can help avoid discovering expired or degraded items in the middle of an outage. For longŌĆælife electronics, periodic powerŌĆæup tests and health checks under your preventiveŌĆæmaintenance program can serve a similar purpose.

A LinkedIn piece on inventory risk management stresses that inventory teams must be trained and empowered to make timely decisions during disruptions, including adjusting policies, tuning safety stock, and activating contingency plans. OSHA and Designed Conveyor Systems both highlight that emergency planning is only effective when employees are trained on the plans, drills are conducted, and leaders are clearly identified. SBN adds that training and drills help staff locate and use emergency supplies and reveal gaps that can be corrected.

For DCS spare parts, that means defining ownership that crosses traditional silos. OT engineers, maintenance planners, warehouse staff, and procurement all have a piece of the puzzle. Teams need to understand which DCS parts are considered emergency inventory, how to access them, what authorization is required to use them, and how to initiate replenishment afterward. They also need basic awareness of cybersecurity and configurationŌĆæmanagement requirements, especially when replacing networked devices, as CISA warns that OT environments are complex and interwoven with business systems.

Drills should not be limited to evacuation and first aid. Periodically walking through a simulated DCS hardware failure and verifying that teams can locate the correct spare, install it safely, restore control, and update records is an excellent way to test not only the hardware but also the procedures and training you have put in place.

Zenventory and SBN both recommend regular audits and stock checks for emergency inventories to prevent overstocking, stockŌĆæouts, and deterioration. Grainger notes that full annual counts are disruptive and instead advocates for more frequent, targeted cycle counts, supported by automated forecasting and reordering systems. They caution that historical usage data is often distorted by ad hoc behaviors, which is another reason to rely on structured counts and systemŌĆædriven processes.

In DCS spareŌĆæparts management, cycle counts can focus on highŌĆæcriticality items: controllers, communication modules, network switches for control networks, and critical power supplies. These counts confirm that spares are present, correctly labeled, and in usable condition. They also confirm that records match reality so that when you query your system during an emergency you can trust what it tells you.

Metrics should connect back to the service levels and risk posture you defined earlier. You can track the frequency of DCS hardware failures, mean time to repair with and without onŌĆæhand spares, the number of emergency orders placed because spares were missing, and the age or turnover of critical spares. GraingerŌĆÖs and IBMŌĆÖs findings that better inventory optimization can significantly cut unplanned downtime and inventory cost suggest that even modest improvements in these metrics can have outsized impact on production and maintenance budgets.

Continuous improvement comes from using those metrics to adjust. If you consistently see DCS failures in certain modules without enough spares on hand, you increase stocking levels or add equivalents. If some spares never move and represent obsolete or lowŌĆærisk items, you can gradually rationalize them, freeing capital for higherŌĆævalue inventory.

Start with your OT asset inventory and criticality assessment. Core DCS controllers that run entire process units, communication modules that connect safety systems and remote areas, and key network switches in your control network usually sit at the top of the list because their failure has immediate, plantŌĆæwide impact and they are often singleŌĆævendor, longŌĆælead items. I/O modules serving highŌĆæhazard or productionŌĆæcritical loops and smart field devices that protect people or the environment typically follow.

Where components are genuinely commodity items with short lead times, multiple suppliers, and low criticality, a leaner, justŌĆæinŌĆætime approach can be appropriate. Examples might include noncritical workstations that can be quickly rebuilt or standard network components not carrying control traffic. The distinction should come from riskŌĆæbased planning: if losing the item does not materially affect safety and you can reliably replace it within your target recovery time, carrying surplus stock may not be necessary.

A review makes sense whenever something important changes: a system upgrade, a new unit, significant changes in production rates, or changes in suppliers and lead times. It is also wise to revisit your strategy after any major incident or near miss and to align it periodically with your broader emergency response and OT cybersecurity programs. ScancoŌĆÖs disasterŌĆæplanning guidance and OSHAŌĆÖs emergency planning principles both emphasize that emergency plans are living documents; DCS spareŌĆæparts management is no exception.

In the field, I have rarely seen a plant regret investing in a thoughtful, riskŌĆæbased DCS spareŌĆæparts strategy before a crisis. Walking your process, mapping OT assets, and designing emergency inventory with the same rigor you apply to safety systems turns spare parts from an afterthought into a deliberate defense. When the next unexpected event hits, you will be glad those decisions were made on a quiet day, not under flashing alarms.

Leave Your Comment