-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for ŌĆ£ŌĆØ.

When you run an automated plant, you learn quickly that losing power is not a theoretical risk. It is a PLC frozen mid-cycle, a line full of product going to scrap, and operators standing in the dark. Over the last few years, I have been called into facilities during storms, grid events, and utility failures, and a pattern keeps repeating: they ŌĆ£have a generator,ŌĆØ but they do not have a complete, deliverable emergency power system.

Emergency power is not just about kW on a spec sheet. It is about the practical ability to deliver that power, on time, to the right bus, and keep it there safely. That is a logistics, integration, and maintenance problem as much as it is an electrical one.

In this article, I will walk through how to think about emergency power supply modules and, just as important, how to plan their delivery so your control systems stay energized when the grid does not.

Power outages are getting longer and more frequent. National-level statistics cited in resilient power guidance from federal agencies and NFPA show that nearly all customers see at least one outage per year, with average interruptions measured in hours, not minutes. CISA materials referencing energy-data sources note that U.S. customers experienced roughly 7 hours of outages per customer in a recent year. An emergency communications provider highlights that a single hour of downtime can cost businesses many thousands of dollars in lost productivity and revenue.

In data centers, a Device42 guide notes that power outages are a major cause of downtime, and another source cites power interruptions as responsible for about a third of data loss events. Healthcare white papers emphasize that even short disturbances can jeopardize patient safety and life-support systems. These sectors invest heavily in emergency and standby power because they understand power loss as an existential risk, not just a nuisance.

Industrial automation plants are no different. A line of drives, PLCs, and SCADA servers has the same fundamental dependency on stable power as a data center rack. The difference is that we often underestimate the logistics: how the emergency power supply modules arrive, where they sit, how they connect, who operates them, and how quickly the system actually takes over.

If you want to keep your controls energized, you have to design and deliver emergency power the way critical infrastructure does.

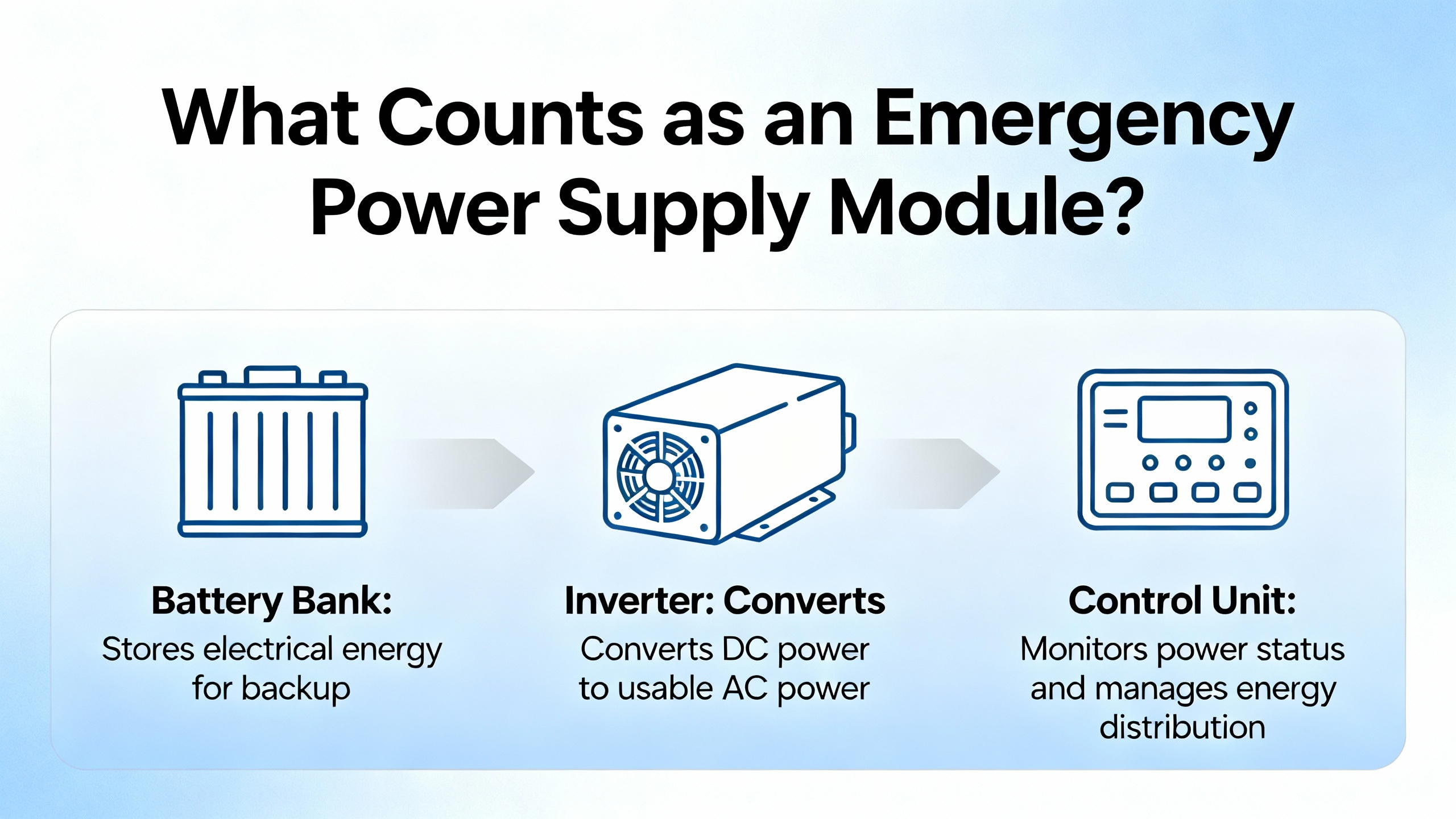

The standards language can be confusing, so it is worth clarifying a few terms from NFPA 110 and related guidance.

NFPA uses ŌĆ£Emergency Power SupplyŌĆØ (EPS) for the source of emergency power, usually an engine-driven generator. The ŌĆ£Emergency Power Supply SystemŌĆØ (EPSS) is the whole stack: generator, automatic transfer switches, controls, distribution, and associated equipment.

In real plants, emergency power supply modules span several categories.

| Module type | Core role in emergency power | Typical industrial use case |

|---|---|---|

| Generator set (EPS) | Provides medium- or long-duration backup when utility fails | Keeps life safety, process controls, and critical loads on |

| Automatic transfer switch (ATS) | Detects utility loss and transfers loads to emergency source | Switches MCCs, critical panels, or UPS input to generator |

| UPS system | Bridges the gap during generator start and cleans power | Supports servers, PLCs, HMIs, and sensitive instruments |

| Power distribution units / switchgear | Safely distribute and protect emergency power | Feeds panels, MCCs, and rack-level loads under backup power |

| Modular power supplies / RPS / BBUs | Provide redundant, hot-swappable dc to electronics | Redundant server/PLC power, high-availability IT/OT loads |

| Mobile/rental generator modules | Temporary or portable power blocks | Planned outages, construction phases, seasonal backup |

In healthcare, an emergency power system integrates generators, transfer switches, UPS units, and distribution into a coordinated architecture that keeps life-safety, critical, and equipment branches energized. Data center guidance describes a similar ladder, from high-voltage utility feeds through switchgear and UPS, to generators, PDUs, and finally rack-level distribution. That same layered model works well for factories.

NFPA 110 classifies EPSS installations by ŌĆ£Level,ŌĆØ where Level 1 systems protect life-safety loads such that failure could cause loss of life, and Level 2 systems protect important but non-life-safety loads. NFPA also defines ŌĆ£TypeŌĆØ (how fast acceptable power must be restored; for example, Type 10 means within 10 seconds) and ŌĆ£ClassŌĆØ (how long the system must run without refueling). Healthcare and mission-critical facilities lean toward Level 1, short Type, and longer Class ratings. Many industrial sites should be thinking the same way for parts of their infrastructure.

Hospitals are the gold standard for emergency power. A healthcare-focused white paper describes emergency power systems that treat power as ŌĆ£always on,ŌĆØ segmenting loads into life-safety, critical, and equipment branches, and backing them with generators, ATSs, UPS units, and strict testing protocols. NFPA 99 and NFPA 110, together with codes like NFPA 70 (NEC) and NFPA 101, set rigorous expectations for performance and maintenance.

From these environments, a few clear design patterns emerge.

First, they use layered, diversified power architectures. CISA guidance on resilient power emphasizes combining normal utility service with on-site generation, UPS, and, when feasible, battery storage or microgrids. That diversity reduces dependence on any single component. For an industrial site, that translates directly into pairing well-sized generators with UPS coverage for control systems, not relying solely on one or the other.

Second, they treat testing and maintenance as non-negotiable. NFPA 110 and NFPA-based guidance require weekly and monthly inspections, monthly generator exercising under load, periodic load-bank testing, and formal acceptance tests witnessed by an authority. A federal fact sheet stresses realistic load testing and incorporating power loss into drills. Hospitals understand that the only way to trust an emergency system is to run it, repeatedly, on purpose.

Third, they manage fuel and physical risk. Resilient power guidance recommends sizing on-site fuel, maintaining multiple fuel supplier contracts, testing fuel quality, and physically protecting generators and switchgear from flooding, wind, wildfire, and extreme temperatures. Industrial sites that place their generators in unprotected basements or exposed yards without considering these factors are inviting the same problems that have sidelined backup systems in storms and floods.

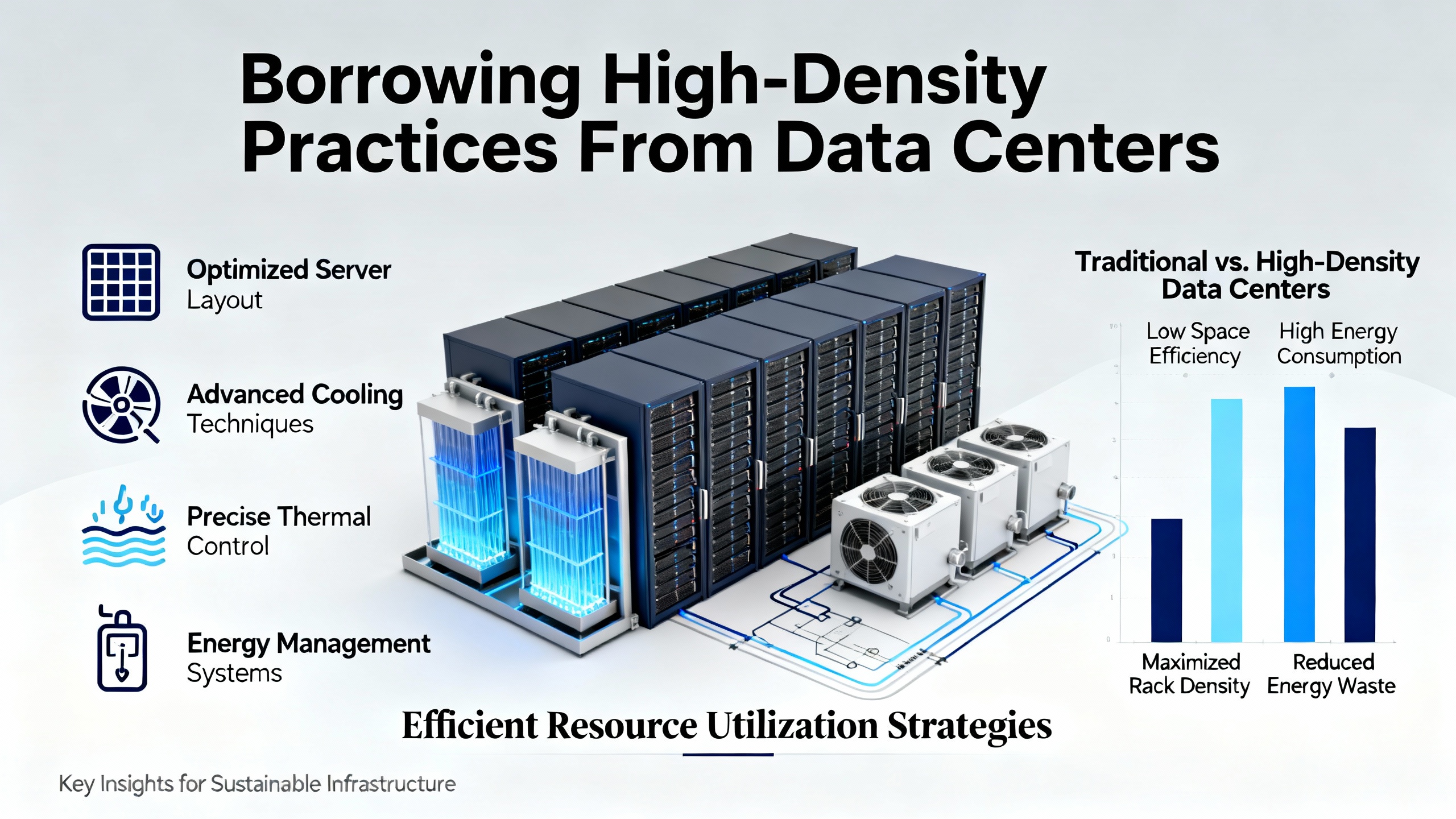

Data centers extend those principles with a strong focus on efficiency and modularity. Power strategy articles point out that typical electrical distribution losses can be around 12 percent of data center energy, costing hundreds of thousands of dollars per year in a mid-size facility. That has led to higher-voltage distribution, transformerless UPS designs, simplified distribution paths, and highly efficient power supplies and PDUs. Flex Power Modules, for example, describes quarter-brick dc/dc converters delivering well over a kilowatt each with high isolation and efficiency, enabling very dense, reliable power distribution to AI-class processors. FSP highlights redundant server power modules with up to 96 percent conversion efficiency, operating from about 32┬░F up to roughly 130┬░F and at altitudes of around 16,400 ft.

You may not be running a hyperscale data center on your factory floor, but many of your control, networking, and MES servers share the same power electronics DNA. Their expectations for clean, tightly regulated power and redundant feeds are identical.

Every practical emergency power plan starts by deciding what absolutely must remain powered.

Thompson Power Systems frames this as the first question in their contingency planning checklist: will you back up the entire facility, or only critical loads such as life-safety systems, production machinery, servers, process controls, HVAC, compressed air, and pumps? CISAŌĆÖs resilient power guidance adds a broader view, urging operators to identify ŌĆ£mission-essential functions,ŌĆØ map the equipment and loads that support those functions, and prioritize them for backup or rapid restoration.

In a control-heavy plant, that often breaks down into several categories. Life safety systems such as emergency lighting, fire alarms, smoke control, and in some cases elevators for evacuation are at the top of the list. Critical controls and automation come next: the PLCs, drives, control panels, instrumentation, and associated servers that are needed to either keep processes within safe limits or bring them to a safe, orderly stop. Then come supporting infrastructure loads such as compressed air, chilled or process water, critical HVAC for control rooms and equipment rooms, and key IT and security systems.

NFPA 110ŌĆÖs Level 1 concept is worth applying to your own loads. If losing power to a particular system could realistically result in serious injury or worse, it belongs on a Level 1-like branch in your own design, with the fastest transfer time and the most robust backup. If the impact is primarily economic, it may live on a Level 2-style branch or be left unpowered during an extended outage.

The common mistake I see on site is skipping this analysis and assuming that ŌĆ£the generator will handle it.ŌĆØ That leads to undersized units, overloaded feeders, or, just as bad, overbuilt systems that try to run everything and become too expensive to maintain. A disciplined critical-load definition is the foundation for sizing and delivering the right emergency power modules.

Once you know what must remain energized, the next step is to design the path that power will take from source to load under emergency conditions.

A data center power guide describes the typical chain as utility high-voltage feed, step-down transformers, switchgear or automatic transfer switches, UPS for conditioning and short-term backup, generators for extended outages, PDUs, remote panels, and finally rack-level circuits. That is very close to what we implement in industrial automation projects, even if the last step feeds control panels and MCCs instead of server racks.

CISA and NFPA guidance stress redundancy. Uptime Institute tiers, widely used in data centers, define clear availability expectations: basic single-path designs can see more than a day of annual downtime, while fully redundant, fault-tolerant architectures target less than an hour. Industrial plants rarely aim for Tier IV-level fault tolerance across the entire site, but the principle applies: for your most critical control and safety loads, a single point of failure is a bad bet.

Power quality cannot be an afterthought. A power distribution article points out that poor power quality problems such as harmonics, transients, and voltage imbalance can cause resets, data errors, UPS alarms, overheating, and even arc-flash events. They note that a voltage imbalance as small as about 3 percent can increase motor currents by nearly a third, accelerating wear and driving up energy use. Their recommendations start with measurement and analysis, followed by power conditioning. For many facilities, that means specifying modern double-conversion UPS systems that can actually improve the sine wave quality compared to the utility feed, and using automatic voltage equalizers to keep phase voltages tightly balanced.

In practical terms, an industrial emergency power chain that has proven reliable across multiple projects tends to look like this in concept. Utility feeds enter at medium voltage and are stepped down through high-efficiency transformers to main switchgear. Automatic transfer switches or switchgear with transfer capability detect loss of utility and connect designated buses to generator outputs. UPS systems sit in front of the most sensitive loads, such as control networks and critical servers, providing ride-through during generator start, filtering disturbances, and smoothing any transfer events. Downstream, PDUs and branch panels distribute power to control cabinets, MCCs, and IT racks, ideally with metering and phase balancing. Where possible, higher-voltage distribution is used within the plant to minimize copper size and I┬▓R losses, with final step-downs near the loads.

The details vary, but the principle holds: a simple, well-understood path with well-sized emergency modules and good power quality is far more reliable than a complex, improvised patchwork.

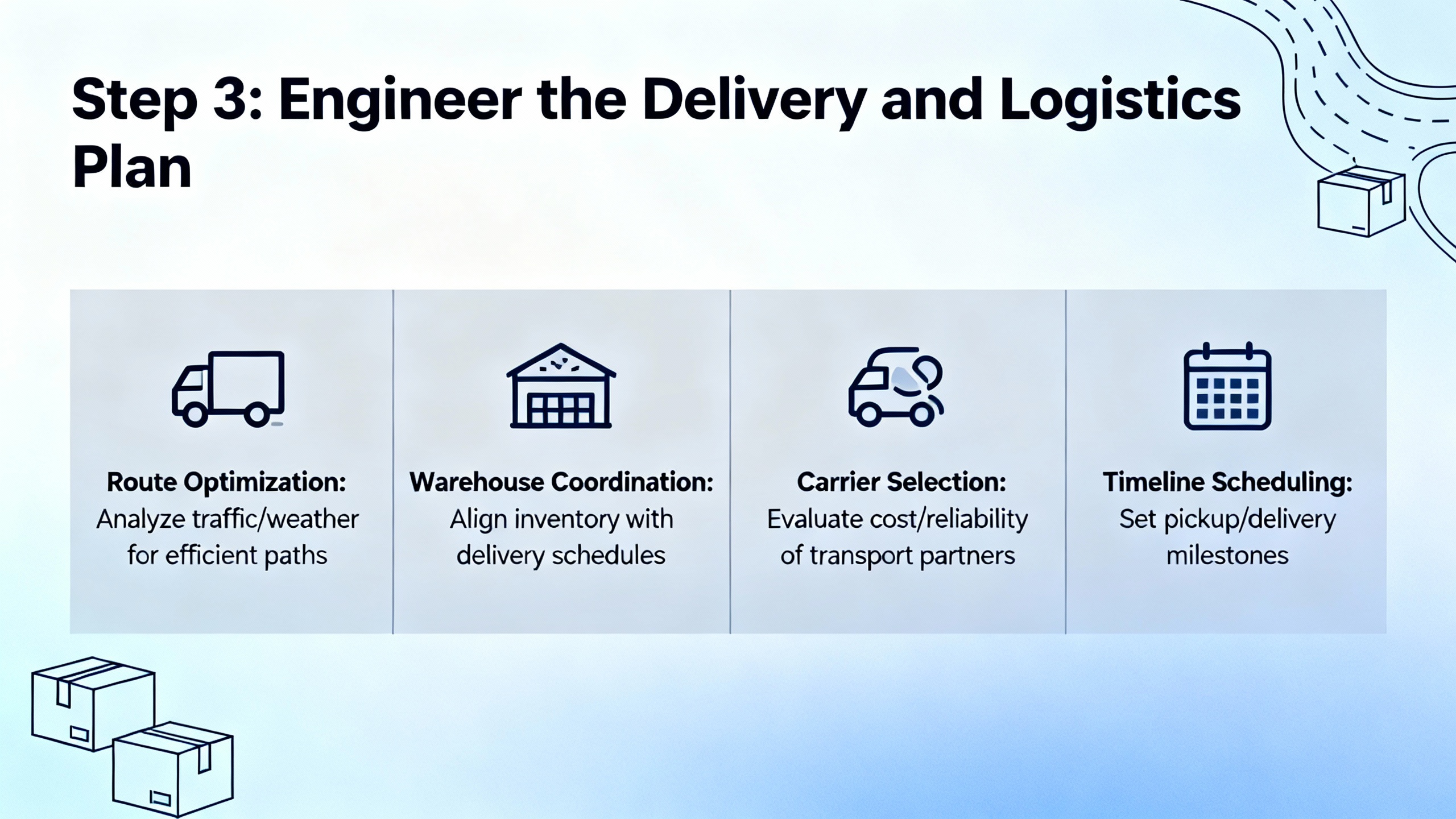

Having the right equipment on a one-line diagram is not enough. The ŌĆ£deliveryŌĆØ part of emergency power supply modules is where many industrial sites fall down.

A planning article notes that mobile generator sets have roughly quadrupled globally over the past decades, covering everything from small units for homes and offices to modules capable of supplying around 2 megawatts to large buildings. Another procurement-focused piece argues that renting generators is often the better choice for temporary or seasonal needs, given lower upfront costs, scalability, no permanent infrastructure, and the fact that service is typically handled by the rental provider.

For industrial sites, the practical choice is usually a mix. Permanent generators and UPS systems cover your highest priority, Level 1-like loads. Mobile or rental generator modules cover planned outages, construction phases, seasonal peaks, and contingency scenarios where the permanent system is offline for maintenance.

One powerful tactic described in emergency power planning literature is a ŌĆ£right of first acceptanceŌĆØ contract. In this arrangement, you pay a retainer so specified generator modules are reserved for your use during an emergency and cannot be committed elsewhere without your consent. When local demand spikes after a hurricane or wildfire, that contract can be the difference between getting a generator in hours versus waiting days.

Structured buy-versus-rent analysis, as recommended by procurement experts, should include lifecycle costs, utilization patterns, project timelines, and long-term maintenance obligations. For heavy industrial users, owning core generators and transfer gear while pre-negotiating rental contracts for surge coverage is often the most resilient combination.

On real projects, I have seen beautifully engineered generator schemes fall apart because there was nowhere to park a trailer within reach of the switchgear, or because there was no safe way to route large temporary cables into the building. ThompsonŌĆÖs emergency power planner emphasizes exactly these logistics details: clearly identified electrical connection points, level paved parking for generator trailers, safe cable routes, adequate clearance from traffic and trees, environmental protections, and physical security such as fencing.

Data center construction guidance extends this into a full delivery and scheduling strategy. They advocate just-in-time delivery of large power components, so switchgear, UPS units, generators, and distribution gear arrive only when needed, minimizing storage risks and congestion. Multi-phase delivery is essential, with careful sequencing so that, for example, switchgear is on site and set before UPS modules arrive, and backup power is fully tested before IT equipment is delivered.

These projects rely heavily on RFID or barcode tracking to log and trace every major component, secure, climate-controlled storage for sensitive equipment such as UPS electronics, and restricted access to prevent theft or tampering. The same practices scale down to an industrial plant commissioning a new generator and UPS: know where the unit will sit, how it will be secured, what environment it will see, and how it will be tracked during delivery and installation.

Emergency logistics guidance for utilities adds another dimension: pre-positioning and route planning. Utilities are urged to identify transportation routes prone to flooding or closure, evaluate storage site vulnerability, and plan to relocate assets out of harmŌĆÖs way when there is advance notice of storms or wildfires. They establish backup suppliers, pre-position inventory such as fuel and repair parts in less vulnerable locations, and plan staging areas that can be accessed even when local roads are compromised. For industrial operators located in hazard-prone regions, it is worth adopting the same mindset: think about where your emergency modules live and how you will physically move them when normal access routes are disrupted.

Predictive supply chain analytics and AI-driven logistics platforms are increasingly used on large projects to forecast delays, adjust schedules, and optimize vendor selection based on real-time shipment data and external risk signals like weather patterns and transportation bottlenecks. Even if you are not running such platforms yourself, you should be asking your generator and UPS suppliers how they manage these risks and how they will communicate them to you during an event.

Emergency generator sourcing guidance places procurement in a central role. They recommend cooperating with operations to forecast seasonal power needs, define technical specifications, and plan around lead times and peak outage seasons such as hurricane or wildfire periods. Early release of requests for information to rental providers helps confirm site feasibility and establish realistic timelines, while milestones and risk-mitigation steps reduce the chance of delays when demand spikes.

Supplier selection criteria highlighted in emergency power planning articles are pragmatic and directly applicable to industrial automation sites. Preferred suppliers maintain adequate in-country inventory or rapid import capabilities, provide generators and full accessory sets (transformers, load banks, panels, fuses, cable), offer training and even operational staff, operate multiple depots for geographic resilience, have strong emergency track records with references, and agree to clear service terms.

Total cost of ownership analysis needs to separate fixed costs such as rental fees, cabling, switchgear, trailers, and fuel tanks from variable costs like labor, fuel markups, delivery and removal, and maintenance rates. A should-cost analysis and market benchmarking support better negotiations, including multi-year and bundled service contracts. But the advice is clear: do not chase the lowest headline rental rate if it comes with weak service, poor safety records, or limited availability when you need it most.

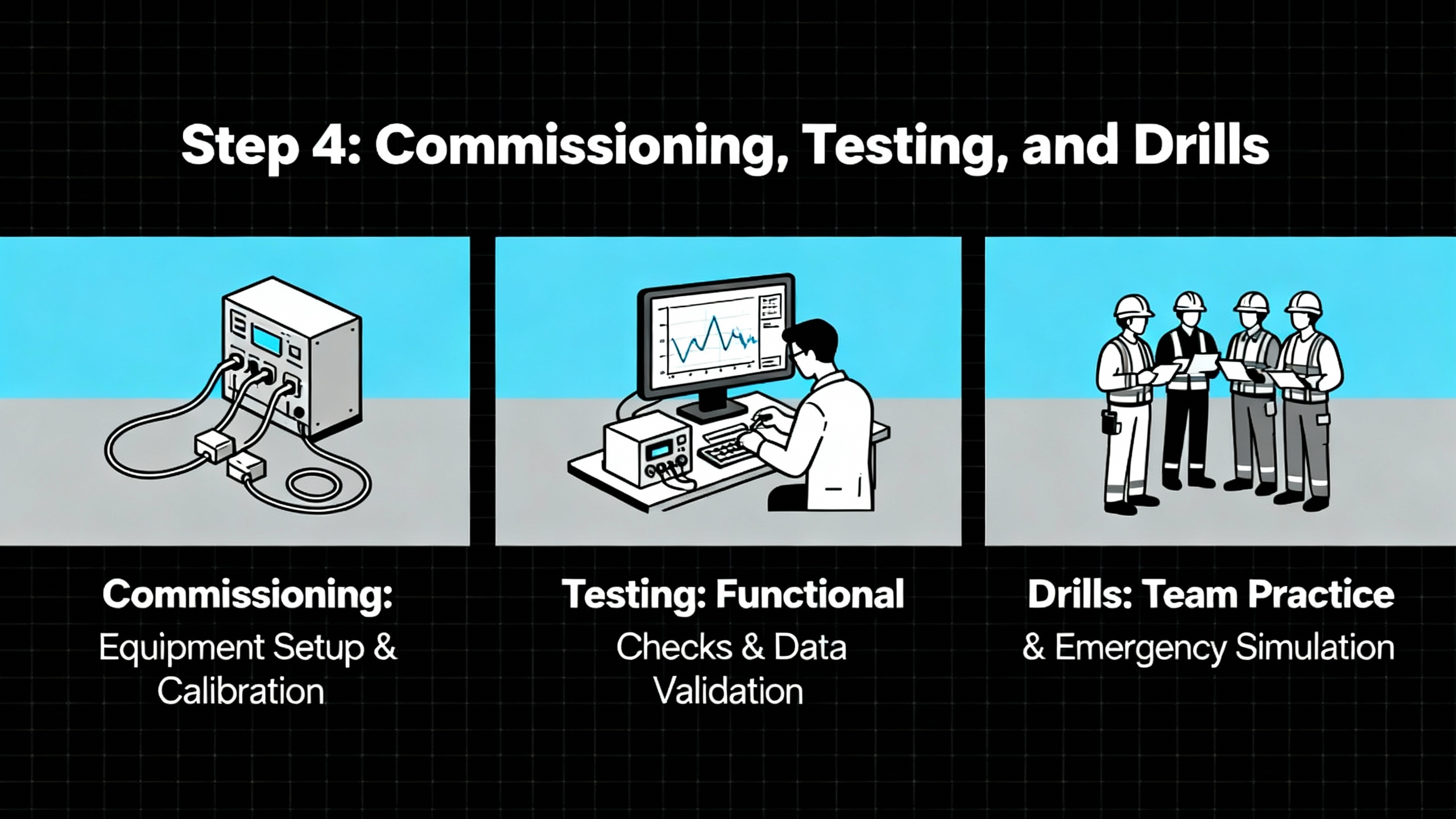

A technically solid, logistically realistic emergency power system still fails if you do not test it thoroughly and regularly.

NFPA 110 and NFPA-based EPSS guidance define a structured testing and maintenance regime. Initial acceptance testing is required after installation or major changes and must be witnessed or approved by the local authority having jurisdiction. It includes on-site full-load testing, cycle crank testing, safety checks, shutdown verification, and confirmation that factory tests are valid in your environment.

Routine inspections and exercises are then mandated: weekly inspections for Level 1 generators, monthly generator exercising, and triennial load-bank tests for Level 1 systems to confirm they can carry their assigned loads under realistic conditions. Transfer switches and paralleling gear must be inspected, cleaned, and tested by transferring from normal to alternate power and back, verifying that the controls behave correctly. Battery systems supporting the EPSS require regular inspections and testing, whether they are traditional wet cells or maintenance-free types, to ensure they will start and support the generator when needed.

Fuel quality management is another critical requirement. NFPA 110-based guidance recommends at least annual fuel quality testing to detect degradation, along with appropriate tank sizing, safe storage (often in fire-rated locations), and protection measures such as spill containment sized to the tank volume. Both Level 1 and Level 2 systems are expected to be exercised under load monthly; simply idling a diesel generator is discouraged because it can cause unburned fuel to accumulate in the exhaust, a condition known as wet stacking.

Thompson Power Systems recommends conducting a full ŌĆ£dry runŌĆØ drill before an actual outage, with both internal staff and the rental supplier walking through the plan as if it were real. The goal is to confirm roles, measure time from power loss to generator pick-up, and verify correct voltages and connections. AlertMediaŌĆÖs outage planning guidance similarly emphasizes drills, simulations, and low-cost tabletop exercises to expose gaps, train team members, and refine procedures.

CISA encourages organizations to integrate resilient power planning with continuity of operations and emergency operations plans, so roles, decision authorities, communication paths, and shutdown or load-shedding criteria are defined in advance. Emergency logistics guidance for utilities recommends multi-party exercises that include not only internal staff but also logistics providers and key suppliers, to stress-test coordination under realistic pressure.

From an automation perspective, I strongly recommend including your PLC and SCADA teams in these drills. You want to see how your control systems behave on real transfers, what alarms fire, how long it takes for HMIs and servers to come back if they do drop, and whether your sequence of events recorders are capturing the events you need for troubleshooting. One power restoration planning article specifically calls out sequence of events recorders at critical sites as a best practice for logging the timing and sequence of electrical events and supporting root-cause analysis after an incident.

Data centers have spent years optimizing how they deliver power reliably and efficiently. Many of those lessons map directly to modern factories, especially as they deploy more compute-intensive analytics, vision systems, and edge servers on the floor.

A consulting engineering article explains that legacy data center power chains traditionally step down from medium voltage to 480 V, then to 208/120 V, passing through several conversion stages, each adding losses. Newer architectures raise distribution voltages closer to the racks, such as 415/240 V three-phase, removing one or more transformation stages and targeting a 5 to 7 percent reduction in losses, along with lower cooling loads and smaller conductors. They also explore 380 V dc distribution to eliminate certain rectifier and inverter stages, with potential 8 to 10 percent loss reductions and better integration with dc renewables and storage, while acknowledging challenges such as dc arc protection and a limited field knowledge base.

Energy efficiency initiatives highlight that in a facility with a power usage effectiveness around 1.5, reducing power distribution unit and distribution losses by 10 kW can cut total facility power by roughly 15 kW once cooling is factored in. In a 1 MW IT load data center, trimming PDU and distribution losses from 3 percent to 2 percent reduces wasted power by about 10 kW, saving around 87,600 kWh per year and potentially tens of thousands of dollars in energy costs, depending on local rates.

Practical guidance on PDUs focuses on selecting high-efficiency units (including transformerless designs where appropriate), designing a simplified power path with fewer transformations, distributing at higher voltages where codes and hardware allow, right-sizing PDUs so they operate in their efficient load range, and using metered or intelligent PDUs with per-outlet monitoring to track rack-level power and environmental conditions.

Modular power solutions from manufacturers like Flex Power Modules and FSP show how much power can be delivered in compact, hot-swappable formats. FlexŌĆÖs dc/dc modules deliver up to about 1,600 W continuous in a quarter-brick footprint, with efficiency in the high 80s to low 90s percent when combined in intermediate bus architectures. FSPŌĆÖs CRPS-standard redundant power supplies offer up to roughly 2,400 W each, with 80 PLUS Platinum or Titanium efficiency levels and remote monitoring through power management buses.

For industrial automation teams, the takeaway is not that you should overhaul your entire power distribution to match a hyperscale data center. It is that you should treat the power paths feeding your control rooms, data rooms, and high-density electronics like the critical assets they are. Use efficient, monitored PDUs, redundant high-efficiency power modules where they are justified, and streamlined distribution paths. The result is not only lower energy waste and heat, but also more predictable behavior when the emergency power system kicks in.

Equipment and delivery plans are only half the battle. Day-to-day operational discipline is what keeps emergency power systems ready.

Outage-planning guidance emphasizes maintaining accurate, multi-channel contact information for employees and key external partners such as fire services, utilities, and emergency management. They advise defining an emergency response team in advance, including an incident commander, evacuation route guides, a communication lead, and an energy lead responsible for backup power, generators, lighting, and alternate locations.

Battery planning guidance aimed at users of power-dependent medical devices offers surprisingly relevant lessons for industrial battery-backed systems. It stresses keeping a clear plan for how batteries will be recharged when grid power is unavailable, understanding the expected runtime of each battery, following strict recharging schedules if your emergency strategy depends on stored batteries, and choosing equipment that uses battery types that are easy to source locally. The parallels to UPS battery strings, control-system backup batteries, and even remote instrumentation power are obvious.

All major guidance documents agree on the need for good documentation and continuous improvement. NFPA-based EPSS best practices call for comprehensive written plans, accurate one-line diagrams, detailed logs of inspections, tests, training, and repairs, and periodic third-party audits. Outage-response frameworks recommend that after each event, organizations assess injuries, damage, financial loss, and data impacts; document lessons learned; update plans and procedures; and share insights internally. Supply chain resilience guidance urges emergency managers and operators to identify critical commodities and services, map how they move from source to end user, and develop mitigation and contingency strategies that account for vulnerable populations and small businesses.

From an automation engineerŌĆÖs standpoint, this is where you close the loop. After each drill or real outage, sit down with operations, maintenance, IT, and safety, and ask pointed questions. Did the generator start when expected? Did the ATS transfer correctly? Which HMIs or servers did not come back cleanly? Were there nuisance trips on drives? Did your sequence of events recorder capture enough detail? Were any manual workarounds needed that should be incorporated into procedures? Then feed those answers back into both your electrical design and your emergency response plan.

To make this more actionable, it helps to think of your emergency power delivery in maturity stages.

| Maturity level | Typical characteristics | Main risks |

|---|---|---|

| Basic | One generator, limited documentation, minimal testing, ad hoc rental plans | Long outages, unsafe improvisation, unclear priorities |

| Intermediate | Defined critical loads, permanent generator and UPS, some drills | Gaps in logistics, weak supplier contracts, incomplete testing |

| Advanced | Layered EPS/EPSS, robust logistics, tested rental and fuel contracts, E2E drills | High resilience but requires ongoing discipline and investment |

Most plants I see fall somewhere between basic and intermediate. The move to advanced is less about exotic technology and more about integrating standards-based design, solid supplier relationships, and disciplined operational practices.

Contingency planning guidance suggests starting with critical loads rather than assuming full-facility coverage. For many plants, powering life safety systems, process controls, critical production lines, and core IT is sufficient to maintain safe operation and revenue flow during an outage. Full-plant backup is possible, but it drives up generator size, fuel requirements, and maintenance costs. A structured load-prioritization exercise, using the mission-essential functions concept from resilient power guidance and the critical-load examples from contingency planners, is the most defensible approach.

Procurement experts and emergency power planners both indicate that renting can be very effective for temporary or seasonal needs, especially when paired with proactive sourcing strategies and strong supplier relationships. Renting shifts maintenance, some logistics, and technology refresh risk to the provider. However, for facilities where power loss is truly unacceptable, owning core generators and transfer infrastructure, combined with pre-negotiated rental agreements for surge capacity, offers a better resilience profile. A total cost of ownership analysis that separates fixed and variable costs and considers outage risk is the right way to decide.

NFPA 110-based guidance recommends weekly or monthly inspections of generators and associated equipment, monthly generator exercising under load, and more extensive load-bank testing at least every few years for high-criticality systems. Hospitals and data centers often test more frequently and under more realistic conditions because they cannot tolerate surprises. For industrial plants, aligning with NFPA 110ŌĆÖs schedules and adding at least annual full drills that include generator start, transfer, and restoration, with participation from automation and IT teams, provides a solid baseline.

On a drawing, an emergency power system is a neat set of one-line symbols: generator, ATS, UPS, distribution. On a bad day at a real plant, it is a set of trucks trying to find your loading dock in the rain, a fatigued operator wondering whether it is safe to switch over, and a control room crew hoping their PLCs and HMIs ride through the transfer. If you treat emergency power supply modules as delivered systems, not just purchased hardware, and borrow the best practices from healthcare, data centers, and utility restoration, you can keep your automation powered when the grid does not cooperate. That is the kind of resilience you only appreciate once the lights go outŌĆöand the kind I aim to build into every project.

Leave Your Comment