-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for ŌĆ£ŌĆØ.

When a process plant loses its control system, the clock starts ticking on more than just downtime. You are balancing safety, product quality, regulatory exposure, and the very survival of the business. In manufacturing, studies cited by Siemens and Reuters show that unplanned downtime can run into tens of millions of dollars per year for large producers, and industry data from providers like Kelley Create and IBM show that even a single hour of outage can cost from thousands of dollars for small businesses up to hundreds of thousands of dollars for large enterprises. In a continuous or batch process environment, these numbers are often conservative.

I work in that uncomfortable window between ŌĆ£everything has stoppedŌĆØ and ŌĆ£we are safely back online.ŌĆØ This article walks through how to think about critical process control system recovery as an emergency restoration service, using established disaster recovery and cybersecurity guidance from organizations such as NIST, IBM, Ready.gov, BRCCI, and ISPE, and translating it into what needs to happen on the plant floor.

Most disaster recovery guidance comes from the IT world. It is valuable, but if you simply lift an IT playbook and try to use it on a live production line or in a regulated pharma environment, you will discover gaps the hard way.

In a plant, the control system sits at the intersection of physical equipment, safety systems, and business operations. Losing an email server is painful; losing the PLCs that coordinate a reactor, a furnace, or a high-speed packaging line can cause material damage, scrap, environmental incidents, or safety hazards if it is not handled carefully. Disaster recovery in this space is not only about restoring servers; it is about restoring controlled energy flows.

IBM describes business continuity planning as proactive and focused on keeping essential operations running, while disaster recovery planning is reactive and focused on how systems, data, and services are restored afterward. That distinction is especially important in process control. Your business continuity plan defines how you keep the process safe and, where possible, partially operational during a control system failure. Your disaster recovery plan defines how you rebuild and revalidate the control stack so the plant can return to normal, validated operations.

Across the sources, two metrics appear consistently: Recovery Time Objective and Recovery Point Objective. Cloudian, IBM, NIST SP 800ŌĆæ184, and multiple disaster recovery best practice guides define them in very similar ways. Recovery Time Objective is the maximum acceptable time that a system or process can be down before the consequences become unacceptable. Recovery Point Objective is the maximum acceptable data loss, expressed as how far back in time you may need to restore data.

On the plant floor, RTO might mean that the basic process control layer must be restored within a few hours to avoid product shortages, while less critical reporting systems might tolerate a full day of downtime. RPO might mean you can afford to lose a few minutes of historian data but cannot afford to lose batch genealogy records at all in a regulated environment.

The key is that you cannot set these numbers in isolation. NIST SP 800ŌĆæ184 and Ready.gov both emphasize business impact analysis as the foundation. For each process area, you need to understand what happens to safety, quality, revenue, and regulatory obligations as downtime stretches from minutes into hours and then days. Those answers drive your restoration priorities and the level of redundancy or backup you need.

It is tempting to picture a single dramatic cause, such as a hurricane or a cyberattack. In real cases, the story is usually messier. The research notes cover natural disasters, infrastructure failures, cyber incidents, and human error across multiple industries; the patterns translate directly into control environments.

Sources like Cloudian and Ready.gov describe the core hazard categories: natural events such as floods and storms; infrastructure failures such as power loss or network outages; hardware failures; software bugs; and human error ranging from accidental deletion to misconfiguration.

In a plant, all of these show up as variations on the same theme: control servers that will not boot, PLC racks that are not communicating, historian or MES servers that have corrupted databases, failed switches in the control network, or power issues in the equipment rooms. ComputerOne and Ready.gov both highlight the need to plan not only for data loss but also for the loss of premises and supporting infrastructure such as climate control and conditioned power. That is directly relevant to remote I/O panels, drive rooms, and server closets that keep process control hardware alive.

Human error also plays a larger role than many teams admit. Several sources point out that misconfiguration, weak change control, and lack of training are frequent causes of outages. In control systems, untested logic changes, rushed firmware updates, and undocumented wiring or network changes can fail in ways that look like disasters when the right fault occurs.

The ISPE pharmaceutical case study is a sobering example of what a modern ransomware attack can do. In that incident, ransomware entered through phishing, spread quietly, and eventually encrypted endpoints, servers, backups, and even cloud data over about three months. When it detonated, email and collaboration tools were down, the business continuity and IT disaster recovery plans had to be activated, and it took a coordinated effort with an external security provider to analyze, contain, and decrypt systems.

What matters for process control engineers is that the ransomware had infiltrated backup infrastructure long before the visible outage. NIST SP 800ŌĆæ184 and multiple disaster recovery sources stress the importance of offline or immutable backups and careful protection of backup systems themselves. If your PLC programs, HMI projects, and historian databases are only backed up to online locations that share the same credentials and network paths as production, a modern attack can encrypt them all before you ever know it is there.

In regulated environments, the ISPE study also shows the quality and compliance side of cyber incidents. When manufacturing systems and standard operating procedures are unavailable, quality teams had to create interim paper-based processes, maintain detailed recovery logs, and later prove to regulators that product quality, patient safety, and data integrity had been maintained throughout.

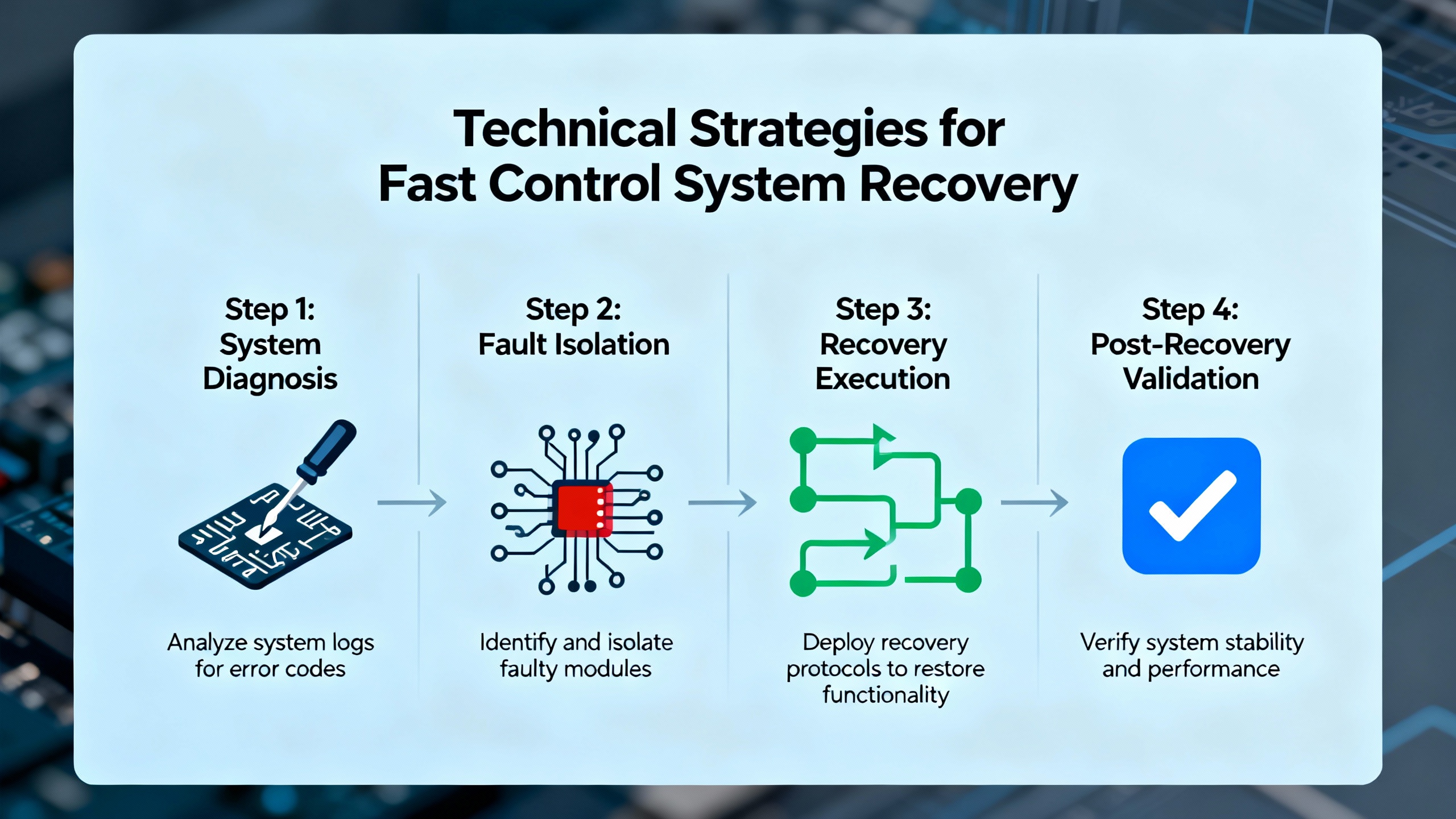

When I walk into a plant during a major incident, the steps that follow are not improvisation. They align well with the phases described by NIST SP 800ŌĆæ184, Ready.gov, and the ISPE case study: reestablish communications, build and activate response teams, communicate and notify, execute the plans, and then analyze and improve. In the control world, those map into a practical emergency restoration lifecycle.

You cannot coordinate a recovery if you cannot reach the people who must make decisions. The ISPE case describes pre-maintained contact lists in a breakŌĆæglass location and a permanent disaster hotline. DataGuard and InfoTech emphasize the importance of clear authority to declare a disaster, 24/7 escalation coverage, and defined criteria for when an issue becomes a crisis.

For a plant, this means that when the DCS or PLC network fails, the first task is to get operations, maintenance, engineering, IT, and quality talking on channels that do not depend on the compromised systems. That may be a tollŌĆæfree hotline, personal cell phones using text messages, or secure cloud collaboration that is logically separated from the plant network. MicrosoftŌĆÖs guidance on disaster recovery with Azure and IBMŌĆÖs advice on war rooms both highlight the value of establishing a central command point with clear roles and escalation paths.

Declaring a disaster should not be a political decision made hours later; it should be based on impact thresholds agreed in advance. If a critical production area has been down beyond its defined RTO, or you see indicators of a cyber incident, the disaster recovery plan should be activated formally. That activation is what unlocks emergency restoration services from vendors, brings in external partners, and authorizes deviations from normal change control that might otherwise be blocked.

Once lines are open and the disaster is declared, the next priority is safety and containment. NIST SP 800ŌĆæ184 stresses coordination between incident response and recovery. You do not rush to rebuild while attackers are still active or while equipment is in an unsafe state.

In practical terms, operations may need to move equipment to a safe state: controlled shutdowns, purging, depressurization, or switching to manual controls defined in the business continuity plan. The ISPE case study describes quality-approved manual workarounds and additional checks when automation is unavailable. That approach is just as relevant for a chemical blender or a bottling line: you might run slower, switch to manual sampling, and record data on paper, but only if those workarounds have been pre-assessed by safety and quality.

On the cybersecurity side, containment might mean logically isolating affected networks, blocking certain traffic at firewalls, or taking compromised servers offline while preserving forensic data. Disaster recovery guidance from NIST, DataGuard, and modern DR testing practices underline that you must understand whether you are dealing with a simple failure or an ongoing cyber incident before you bring systems back.

With the situation stable and contained, emergency restoration work focuses on bringing back the minimum set of systems that restore safe, effective control. Every serious source on disaster recovery, from Cloudian and ComputerOne to IBM and Isidore Group, stresses the need to categorize assets and define recovery priorities based on a business impact analysis.

In a plant, those categories might translate to safety instrumented systems and basic process control as mission critical, supervisory HMIs and historians as highly important, and reporting or training systems as lower priority. The exact mapping should be defined in advance in your disaster recovery plan, not invented during the outage.

The technical activities often follow a predictable sequence. Ready.gov describes starting with an inventory of hardware, software, and data, then defining backup and restoration strategies for each. For control systems, that inventory must include PLCs and remote I/O racks, fieldbus or industrial Ethernet switches, HMI and engineering workstations, servers hosting historians, batch engines, and MES, and the configuration databases that tie them together.

Recovery then proceeds according to the documented runbooks. NIST SP 800ŌĆæ184 recommends scenario-based recovery playbooks, and control environments should have their own. A ŌĆ£loss of control serversŌĆØ playbook might specify how to rebuild virtual machines from templates, restore configuration from known-good backups, and rejoin them to the control domain. A ŌĆ£PLC rack failureŌĆØ playbook might describe hardware replacement, firmware alignment, and program download from an immutable backup repository, followed by verification steps.

Application interdependencies matter here. Disaster recovery guidance from Cloudian and Azure emphasizes mapping dependencies so systems are restored in the right order. In a plant, that means bringing databases and historians up before HMIs that depend on them, reestablishing name resolution and time synchronization before enabling batch engines, and so on. Otherwise, you waste precious time chasing secondary faults caused by starting components against missing services.

Recovery is not complete when a controller starts scanning and an HMI shows green indicators. The ISPE case study highlights quality challenges that apply broadly: documentation for audits, interim processes when standard procedures are unavailable, data integrity when using paper workarounds, and qualification of recovered IT infrastructure and decryption tools.

In controlled manufacturing, every emergency restoration must leave behind a trail that quality and regulators can follow. That means keeping a chronological log of key actions, decisions, and approvals, including configuration changes, system rebuilds, and data restoration steps. NIST SP 800ŌĆæ184 and the ISPE guidance both recommend designating specific personnel to maintain these logs so engineers in the field are not trying to remember details days later.

Validation activities should be risk-based but explicit. For a PLC, that may include checksum verification of the downloaded program against a reference, functional checks of interlocks, and confirmation that safety devices behave correctly. For databases and historians, that may include sampling restored data, checking for gaps around the incident window, and verifying that queries and reports operate as expected. In the ISPE example, the company even qualified decryption tools retrospectively to prove that decrypted data were complete and correct. The principle is the same in any regulated plant: you must be able to defend that the restored system is fit for its intended use.

Only after these checks and documentation steps are completed should systems be formally released back to normal production. That handoff should be explicit, with clear communication to operations, quality, and leadership that the process has moved from emergency restoration back into standard operating mode.

Almost every major guideline, from NIST SP 800ŌĆæ184 and IBM to BRCCI and SBS Cyber, ends with the same message: treat every disaster or serious incident as a source of lessons, not just pain. After the fire is out, schedule an after-action review while memories are fresh. Document what failed, what worked, what took too long, and where plans or inventories were wrong.

Feed those findings into updates of your disaster recovery plan, your architectures, your backups, and your training. ComputerOne, InfoTech, and several other sources caution that outdated, untested plans are a primary cause of disaster recovery failure. Quarterly or at least annual reviews, combined with regular testing, are what keep your emergency restoration capability aligned with evolving systems and threats.

Emergency restoration is a service you deliver under high pressure, but it is built long before the sirens start. The most effective plants treat it as a structured program rather than a set of heroic improvisations.

IBM and DataGuard both stress that a disaster recovery strategy starts with business impact analysis and risk assessment. In a plant context, this means sitting with production, maintenance, quality, and supply chain to map out what happens if each major area goes down. Which lines must be running within the next few hours to meet commitments or prevent shortages? Which utilities, such as compressed air or steam control, are single points of failure?

From these discussions, you derive RTO and RPO targets for each major system, then align technology and staffing choices accordingly. Flexible guidance from Isidore Group is helpful here: not every system deserves the same investment. You prioritize tighter RTO and RPO for safety-critical, revenue-critical, and regulated systems, and accept slower recovery for internal or low-impact systems.

Multiple sources, including BRCCI, Ready.gov, and Flexential, emphasize that a current inventory of hardware, software, and data is essential. Without it, you do not know what you are trying to recover.

For process control, the inventory must go beyond servers and network devices. It should include PLC and DCS hardware with exact model and firmware versions, HMI clients and servers, engineering stations with their software versions and license keys, industrial switches and firewalls, and critical endpoint devices such as maintenance laptops and tablets. BRCCI also points out the importance of including remote-working equipment used by contractors and freelancers; in many plants, that includes vendor laptops used for remote support, which can be both a recovery asset and a potential entry point for attacks.

An effective inventory also tracks backup locations and retention for each asset. SBS CyberŌĆÖs discussion of backup strategies shows why: you want at least multiple copies on different media and at least one offsite copy, with some organizations evolving toward multiple offsite copies including an immutable archive to resist ransomware.

Governance and communication appear in nearly every source. ComputerOne recommends appointing a disaster recovery coordinator and keeping contact details current. InfoTech stresses the need for a named authority who can declare a disaster, backup leaders, and a 24/7 escalation schedule, including nights, weekends, and holidays. Microsoft and IBM recommend defining war room roles, communication channels, and escalation paths in advance.

In a plant, this often means naming a control systems recovery lead, an IT representative, a quality lead, and an operations lead, then documenting who makes which decisions during a crisis. Contact lists for internal staff, vendors, and service providers must be stored in secure but accessible locations that are not dependent on the production network. Communication channels should include at least one non-corporate option, such as personal cell phone numbers, external messaging platforms, or a tollŌĆæfree hotline similar to the approach described in the ISPE case.

NIST SP 800ŌĆæ184 encourages scenario-based recovery playbooks that define technical steps, decision criteria, fallback options, and approval paths. Many DR guides talk about runbooks for restoring servers, networks, and databases. In the industrial world, you need similar documents for control-specific scenarios.

Examples include loss of a primary control room, corruption of engineering project files, failure of a core control network segment, or widespread infection of operator workstations with ransomware. For each, your runbook should describe how to assess impacts, what to attempt locally, when to escalate to emergency restoration services from OEMs or integrators, and what quality and safety approvals are required before returning to production. The ISPE case demonstrates that even interim manual processes and abbreviated procedures should be predefined and risk-assessed where possible.

Emergency restoration lives or dies on the technical foundation you have put in place. The research notes describe a range of backup, replication, and failover patterns. The table below summarizes how some of these apply to control systems.

| Strategy | Description | Key Advantages | Key Tradeoffs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple-copy backups (3ŌĆæ2ŌĆæ1 or 3ŌĆæ2ŌĆæ2) | Several sources recommend keeping at least three copies of data on different media with offsite copies, evolving toward additional offsite or immutable copies. | Strong protection against hardware failures and ransomware, especially when one copy is offline or immutable. | Requires disciplined management, regular restore tests, and storage planning. |

| Offline archives of PLC and HMI projects | Engineering projects and configuration archives stored on media not continuously connected to the network. | Resistant to online attacks that compromise servers and network shares; preserves golden images for rebuilds. | Must be kept in sync with changes and stored securely to prevent unauthorized access or loss. |

| Cold standby (on-prem or cloud) | Minimal infrastructure at a secondary site until failover, as described in Azure and SBS Cyber guidance. | Lower steady-state cost; suitable for systems with higher RTO tolerance, such as reporting or some MES components. | Slower recovery because infrastructure must be built out during the incident. |

| Warm standby | Pre-provisioned lower-capacity infrastructure ready to take over, highlighted in Azure DR patterns. | Faster failover for critical systems without the full cost of hot mirroring; good for control servers and historians. | Ongoing cost and complexity; requires regular synchronization and failover testing. |

| Hot standby and redundant controllers | Fully mirrored systems ready to take over immediately, common in high-availability IT and applicable to critical controllers. | Near-seamless failover for the most critical loops and systems; supports very low RTO. | Highest cost and complexity; must be justified by safety, regulatory, or revenue criticality. |

| DRaaS and cloud-based replication | Disaster Recovery as a Service offerings described by Flexential, Cloudian, and Kelley Create. | Expert management, geodiverse storage, scalable environments for non-real-time systems like historians and MES. | Depends on connectivity and careful integration with on-prem control; not a replacement for local safety-critical control. |

The 3ŌĆæ2ŌĆæ1 rule described by ComputerOne and reinforced by SBS Cyber has become a baseline: keep at least three copies of your data, on two different media types, with one copy offsite. SBS Cyber notes a trend toward 3ŌĆæ2ŌĆæ2 patterns, where two offsite copies are maintained, including at least one immutable cloud archive to resist ransomware and other tampering.

For control systems, these principles apply to more than databases. PLC logic, HMI screens, batch recipes, historian configurations, and network device configs all need versioned backups. Cloudian and others stress regular testing of backups and recovery processes to confirm data can be restored and that RPO and RTO targets can actually be met. In practice, this means scheduling restore drills for randomly selected controllers or servers and verifying that the restored system behaves identically to the reference.

DataGuard and other cybersecurity-focused sources underscore the need to encrypt backups at rest and in transit and to protect backup infrastructure from compromise. NIST SP 800ŌĆæ184 adds that multiple generations of backups should be retained so that you can roll back to a point before malware entered the environment, not just before it detonated.

SBS Cyber and Azure disaster recovery guidance describe a spectrum from manual restore through cold, warm, and hot sites. Translating this to process control helps you decide where to spend money.

For safety instrumented systems and critical basic control, hot or warm redundancy is often justified. That could mean redundant controllers with bumpless switchover, dual networks, or clustered HMI servers. For supporting systems like historians, quality databases, or some MES functions, a warm standby might be adequate, with periodic replication and a tested failover procedure. For lower priority systems such as training environments, a cold restore from backups may be sufficient.

The important point, as highlighted by IBM and Isidore Group, is to align these patterns with clearly defined RTO and RPO and with the business impact analysis. Overprotecting low-value systems wastes budget; underprotecting critical ones invites crises you cannot afford.

Cloud-based disaster recovery and DRaaS receive substantial attention in sources like Cloudian, Flexential, Kelley Create, and SBS Cyber. They emphasize benefits such as scalable offsite replication, expert management, and easier testing, particularly as many organizations move toward hybrid or multi-cloud environments.

In process control, cloud is not where you execute real-time control of valves or drives, but it is a powerful location for hosting secondary historians, analytics, engineering project vaults, and even non-real-time MES components. FlexentialŌĆÖs guidance on DRaaS describes offsite replication, failover capabilities, and expert management that can be especially valuable for plants without deep in-house IT and security resources.

The tradeoffs are consistent with the general DR guidance: you must design around connectivity, data sovereignty, and security. DataGuard stresses that clear responsibility and staffing models are needed, including understanding what external providers will and will not do during incidents. Contracts and service level agreements must align with your RTO and RPO targets, and your incident management process must specify when and how cloud failover is invoked.

Multiple sources agree on a hard truth: many organizations either never test their disaster recovery plans or test them so infrequently and superficially that the plans are effectively unproven. InfoTech notes that a large fraction of businesses test rarely or not at all, and SBS Cyber reports that light tabletop-only exercises are insufficient to validate real readiness.

Tabletop exercises have value for walking through roles and communication, but they cannot prove that systems will actually come up. SBS Cyber outlines a testing lifecycle progressing from plan reviews and tabletop exercises to component tests, parallel tests, and full failover with failback. Flexential and BRCCI recommend at least annual testing, with more frequent tests for higher-risk environments or after significant changes.

For process control, a realistic testing program might include periodic restoration of PLC projects to test stands from backup media, simulated failover of redundant servers during planned maintenance windows, and end-to-end recovery tests for secondary systems such as reporting databases or cloud-hosted historians. The key, as emphasized across the DR literature, is to measure the results: track actual recovery times against RTO targets and actual data loss against RPO targets, and use the gaps to drive improvements.

Disaster recovery is not just a technology problem; it is a people and process problem. BRCCI emphasizes staff training and role clarity. DataGuard stresses involving management, legal, and communication teams, not only IT. The ISPE case illustrates how deeply quality must be involved in recovery and interim operations.

In a plant, that means training operators on manual procedures defined in the business continuity plan, training engineers on recovery runbooks and backup tools, and training quality staff on how to document emergency deviations and recovery activities. Including these roles together in drills and simulations helps surface cross-functional issues such as who can approve a temporary change or who must be informed when a system is running in a degraded mode.

Finally, every test should end with a structured review. SBS Cyber recommends formal lessons-learned reports covering scope, objectives, resources used, system performance, achieved RTOs, identified gaps, required updates, and scheduled follow-up testing. NIST SP 800ŌĆæ184 and IBM echo the need for continuous improvement: updating recovery plans, architectures, controls, training, and exercises based on test and incident results.

In practice, these reviews often uncover simple but critical issues: outdated contact lists, scripts that no longer run against current systems, missing backups for new assets, or manual steps that can be automated. Fixing these in peacetime is far cheaper than discovering them at 2:00 AM during an actual plant outage.

Normal maintenance is planned and bounded; it usually happens during scheduled downtime with standard change control. Emergency restoration happens under time pressure, often during unplanned outages or security incidents. It uses many of the same technical skills but must follow a disaster recovery plan that defines priorities, alternative communication paths, streamlined approvals, and quality documentation requirements, as described in guidance from NIST, Ready.gov, and ISPE.

The sources converge on ŌĆ£at least annuallyŌĆØ as a minimum, with more frequent testing for higher-risk environments or after major changes. BRCCI, SBS Cyber, Flexential, and others recommend a mix of tabletop exercises, partial technical tests, and full failover and failback drills. For critical control systems, integrating recovery tests into scheduled outages or shutdowns can provide realistic validation without unacceptable production impact.

Yes, but the implementation must be right-sized. Isidore Group and Flexential both argue that smaller organizations should still have documented plans, clear RTO and RPO, prioritized asset lists, and at least one offsite backup. Where in-house expertise is limited, DRaaS providers and industrial automation partners can supply backup management, cloud replication, and structured testing. The key is to focus first on the systems whose loss would stop revenue or violate safety or regulatory obligations, then grow the program as resources allow.

When you treat critical process control recovery as an emergency service built on rigorous planning, realistic testing, and cross-functional coordination, you move from heroics to reliability. The next time a storm, hardware failure, or ransomware event takes a chunk out of your control system, you want a calm, practiced response: clear authority, known priorities, trusted backups, and a path from safe shutdown back to validated production. That is the difference between a bad night and a business-threatening catastrophe.

Leave Your Comment