-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for ŌĆ£ŌĆØ.

Walk into any plant during a real automation emergency and the pattern is familiar. A major line is down, product is backing up, operators are waiting, and someone from management wants to know exactly how many dollars per minute the outage is costing. Unplanned downtime is not theoretical; studies summarized by Twilight Automation put the average cost of unplanned downtime in manufacturing around hundreds of thousands of dollars per hour, and large automotive lines can lose more than $2,000,000.00 in a single hour of lost production, as reported by Siemens and WorkTrek. In that environment, urgent industrial automation repair is not about heroics. It is about having a disciplined, safetyŌĆæfirst playbook that restores operation quickly, protects equipment and people, and feeds lessons back into your maintenance strategy so you see fewer emergencies next year than you did this year.

This article lays out that playbook from a plantŌĆæfloor perspective. It combines fieldŌĆætested troubleshooting structure, guidance from sources like DigiKey TechForum, Knobelsdorff, Delcon, Develop LLC, Llumin, Twilight Automation, and others, and practical advice you can apply on your next lineŌĆædown call long before an outside integrator can get to your site.

Urgent industrial automation repair is any reactive work where your first goal is to stop production loss and restore a safe, stable state. It typically involves control systems such as PLCs, HMIs, drives, industrial PCs, sensors, and industrial control systems that are embedded in critical processes. The LinkedIn guidance on balancing proactive maintenance and urgent fixes frames this as the ŌĆ£firefightingŌĆØ side of maintenance, in contrast to scheduled preventive tasks. Both are necessary. If you lean too far into routine maintenance and never prepare for emergencies, your team will freeze when something truly unexpected happens. If you lean too far into urgent repair, preventive work slips, backlogs grow, and the plant lives in a permanent state of technical debt.

In practical terms, an urgent repair is a situation where production has stopped or is about to stop, and you must intervene immediately to avoid unacceptable safety, quality, or financial impact. An emergency stop that has locked out a machine, a repeated drive trip on a bottleneck conveyor, a PLC that will not boot, or a critical ICS controller that appears offline for unknown reasons all qualify. Knobelsdorff distinguishes between an emergency stop, which halts equipment immediately and is the most severe, and a cycle stop, which allows equipment to complete a cycle safely. Both are signs that something serious is happening in your automation system and that urgent diagnostic and repair work is needed.

Every minute of downtime matters because you rarely lose only the output of a single machine. You also lose downstream capacity, upstream material flow, labor productivity, and often customer trust. WorkTrek highlights that a single hour of downtime in a large automotive plant can cost up to $2,300,000.00. Twilight Automation consolidates industry surveys showing that plants can see around 800 hours of downtime annually, and that emergency repairs tend to cost three to five times more than planned interventions once you factor in overtime, premium shipping for parts, and scrap.

Those numbers are not there to create fear; they are there to make prioritization concrete. If your line produces highŌĆævalue product, a tenŌĆæminute delay in starting structured troubleshooting can burn more money than a full day of a technicianŌĆÖs time. That is why a clear, repeatable process matters more than any single ŌĆ£trickŌĆØ or shortcut. A methodical approach that reliably finds root causes in minutes instead of hours is the single best lever you have to minimize production loss during urgent repairs.

When equipment is down and pressure is high, safety shortcuts are tempting. DigiKey TechForumŌĆÖs guide to troubleshooting industrial control and automation equipment starts by emphasizing that industrial systems, even when they look benign, can be lethal. Technicians face risks that include electrocution, crushing, burns from arc and blast, entanglement, asphyxiation, and severe hydraulic injection injuries. Knobelsdorff also flags heat as a critical risk, noting that control equipment must stay within the manufacturerŌĆÖs temperature limits to avoid damage and unsafe operation.

The first rule in urgent repair is that no amount of production is worth a serious injury. That means properly applying lockoutŌĆætagout to make equipment electrically, mechanically, pneumatically, and hydraulically safe before you open panels or reach into machinery. It means following Occupational Safety and Health Administration standards and your companyŌĆÖs own safety rules, using the right personal protective equipment for the task, and working with a partner whenever you are in a highŌĆæenergy environment such as a live service panel. DigiKey TechForum specifically warns against bypassing interlocks or working in defeated panels without strict safety controls, because one moment of complacency is enough to cause irreversible harm.

Hydraulic and pneumatic systems deserve special care. The same DigiKey resource points out that you should never use your hands to look for air or hydraulic leaks, because highŌĆæpressure fluid can penetrate skin and cause devastating injuries that require extensive surgery. Use appropriate detection methods and tools instead of improvised practices. A culture where technicians are encouraged to stop work if safety conditions are not met is not a luxury; it is a prerequisite for sustainable urgent repair.

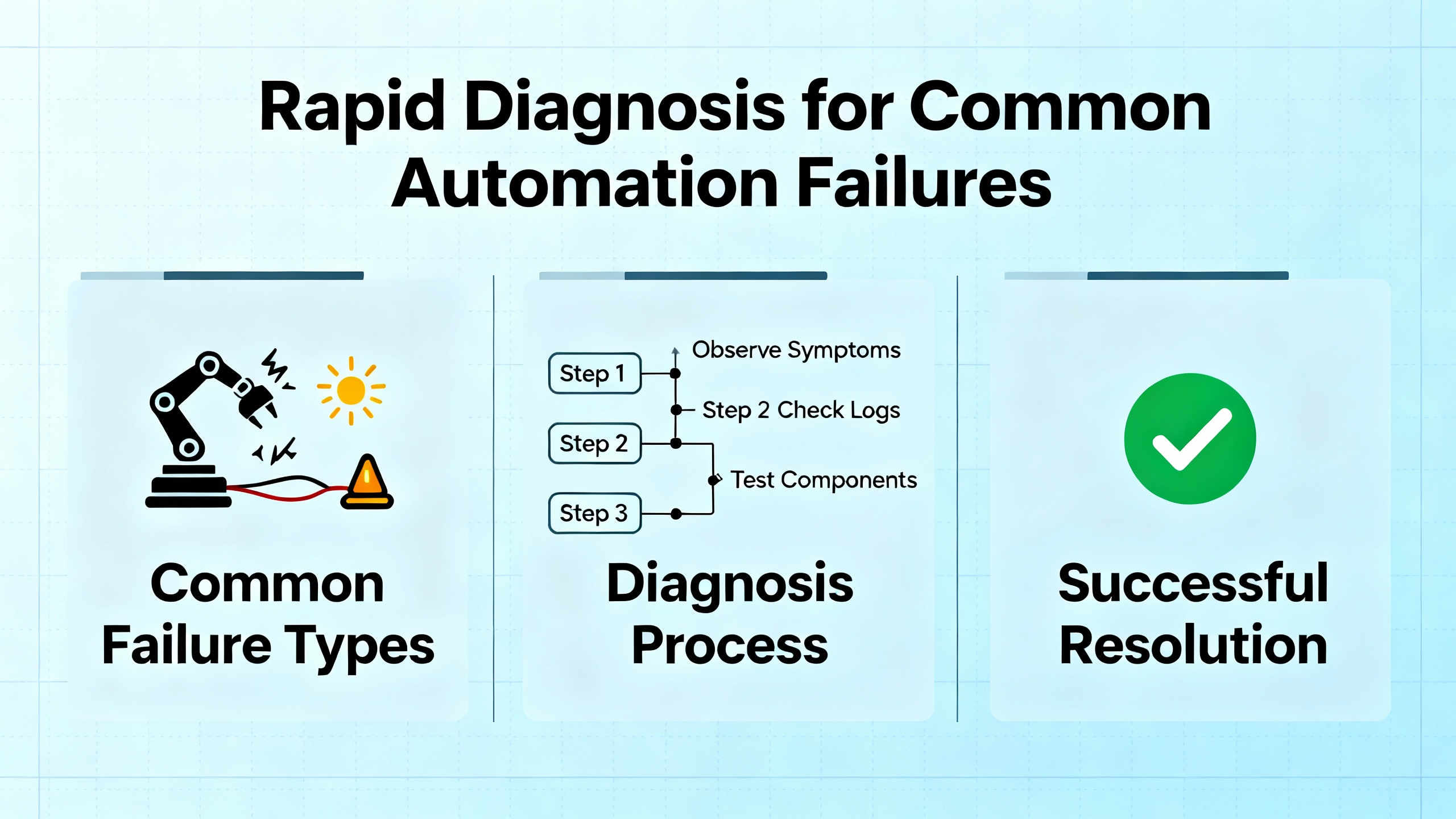

When you are in the middle of an urgent call, the worst thing you can do is poke randomly at wires and parameters. DigiKey TechForum adapts the Navy sixŌĆæstep troubleshooting procedure, originally used for complex military electronics, and shows that it applies well to modern PLCŌĆæbased equipment. Turning that into a plantŌĆæfloor playbook gives you a path you can follow under stress.

You cannot fix what you do not truly understand. Symptom recognition means knowing how the machine behaves when it is healthy and clearly noticing when it is not. This requires familiarity with normal sequences, cycle timing, HMI indications, and alarm behavior. If your team does not know what ŌĆ£goodŌĆØ looks like, they will struggle in an emergency. Running the machine until the point of failure, where it is safe to do so, helps make the symptom concrete. This is where wellŌĆæwritten standard operating procedures are critical. DigiKey TechForum stresses that SOPs are essentially checklists tailored to each machine, similar to aircraft preflight checklists, and they guard against both operator and technician error.

Symptom elaboration goes beyond the first thing you notice. The temptation in a crisis is to fix the first obvious issue and declare victory, only to discover that the underlying problem remains. Instead, take a moment to ask operators what they saw leading up to the failure, review alarm history on the HMI or SCADA interface, and inspect the machine for other anomalies such as unusual noise, smell, or motion. Running the equipment through a full cycle up to the failure point, when safe, helps you see the entire pattern rather than a single data point. Maintaining a service log for each machine, as DigiKey recommends, allows you to capture symptoms and repair actions so future technicians can see repeating patterns and temperatureŌĆædependent or intermittent behaviors.

Once you have a clear picture of symptoms, pause to think. This is where you list the functional areas that could plausibly cause what you see. For a packaging line, that might include the upstream conveyor drive, the main PLC power and I/O subsystem, the safety circuit, or a particular motion axis. The DigiKey guidance warns against ŌĆ£tunnel visionŌĆØ: the tendency to latch onto the first suspicious component while ignoring contradictory evidence, multiple simultaneous problems, or mechanical and operator issues. This is not yet about individual wires or components; it is about identifying which subsystem you will attack first.

Now you move from the list of suspect subsystems to a single one. You use builtŌĆæin indicators such as front panel LEDs on the PLC, field device status lights on valves and sensors, drive displays, and physical motion to decide which function is actually misbehaving. DigiKey TechForum notes that industrial components are designed to help you here; modern PLCs, sensors, and relays provide visual clues about input and output states. The key is to know the machineŌĆÖs timing well enough to interpret those clues correctly. For example, a sensor LED that never turns on might indicate a failed sensor, but it might also be normal if the part is never in front of the sensor under current conditions.

Only after you have narrowed the problem to a specific function is it time to reach for wiring diagrams and test equipment. You divide and conquer, using voltage measurements, continuity checks, or signal tracing to split the suspect path in half repeatedly until you have isolated the exact bad device or connection. DigiKey uses the example of a PLC whose power indicator is off. The suspected blocks might include the mains supply, transformer, protective devices, the twentyŌĆæfour volt direct current supply, and the PLC itself. Checking the voltage at a convenient point or looking at the behavior of field devices that share that supply lets you eliminate entire blocks quickly. This logical ŌĆ£halfŌĆæstepŌĆØ method is far faster and more reliable than randomly swapping components.

Once you have found and corrected the immediate cause, you are not done. Failure analysis is where you ask why the part failed and what you must change so it does not happen again next week. That might involve investigating overload conditions, environmental stress such as heat or dust, poor component quality, or software changes. Documenting the failure, your diagnosis steps, and the final fix in a service log is not paperwork for its own sake; it is building institutional memory. Develop LLCŌĆÖs knowledge base on automated systems maintenance emphasizes that disciplined documentation and checklists are foundational for keeping custom automation at peak performance and for training new staff.

Following these six steps does not slow you down in an emergency; it keeps you from going in circles. Over time, your team becomes faster precisely because they follow the same pattern every time.

A structured process is the backbone. Having a mental library of typical failure modes and quick checks is the muscle that moves that backbone.

When a PLC appears dead, the first instinct is often to suspect the CPU. DigiKeyŌĆÖs troubleshooting example shows why that is risky. If the PLC power light is off, a more likely cause is upstream: a blown breaker, tripped power supply, loose terminal, or short on the twentyŌĆæfour volt direct current bus. The fastest route is to look at other loads on the same supply. If sensors powered from the same supply still respond and their indicator LEDs light, the supply and upstream wiring are probably fine. That narrows the fault to the PLC power feed, protective devices, or the CPU module itself. IndustrialAutomationCo notes that PLCs are also prone to failures from aging backup batteries, corroded terminals, and loose wiring caused by vibration. They recommend replacing backup batteries on the order of every twelve to twentyŌĆæfour months and doing regular terminal inspections, which not only reduce future urgent repairs but can also speed diagnosis when failures occur.

Drive trips and motor failures are among the most disruptive automation emergencies because they often affect primary motion. IndustrialAutomationCo points out that drives typically fail due to overheating, power surges, fan failures, dust buildup, and aging components such as capacitors. Small issues like a clogged filter can escalate into a major shutdown. Knobelsdorff emphasizes that voltage testing across all three phases, under running and idle conditions, helps catch phase loss and undersized power distribution before motors fail. Motor current testing can reveal abnormal loading; elevated current often means failing bearings or mechanical binding, where vibration analysis is particularly helpful in predicting failure before it becomes catastrophic.

In an urgent situation, your quickest wins are to read drive fault codes, check for obvious airflow and cooling issues, and verify supply voltage and motor current against expected ranges. If you can safely restart after addressing a clear and simple cause such as a blocked filter or failed fan, you minimize downtime. At the same time, you should schedule deeper inspection during planned downtime because a drive trip is often a symptom of a larger mechanical or thermal problem.

Industrial PCs and HMIs are the human gateway into the control system, and their failure can cause costly delays. IndustrialAutomationCo notes that these devices often run around the clock in harsh environments and fail due to dust ingress, thermal cycling, hard drive wear, and unstable power. An urgent repair approach starts with basics: verify supply power and protective devices, check cooling fans and vents for dust and blockage, and observe whether the issue is intermittent or repeatable. Using an uninterruptible power supply or surge protection, as suggested in their guidance, can prevent many of these incidents. For HMIs and PCs, maintaining verified backups of application software and configuration can reduce recovery time from hours to minutes when replacement is necessary.

Failures are not always in the control panel. Hyspeco and SDC both highlight how wear, misalignment, and contamination at the machine level can lead to unexpected stops. Routine inspections that look for loose fasteners, worn bearings, misaligned stations, dirty vision systems, and debris in the work area dramatically reduce the odds of a sudden, unexplained stop in the middle of a shift. In an urgent scenario, do not overlook these simple mechanical checks just because the system is automated. Many ŌĆ£mystery faultsŌĆØ turn out to be sensor targets out of alignment, dirty lenses, or small mechanical interferences.

Knobelsdorff calls out electromagnetic interference as a cause of automation emergencies that is easy to miss. Radios, electromagnets, and variable frequency drives can inject noise into control wiring or power rails, causing anything from sporadic misbehavior to complete PLC failure. Even everyday maintenance tools such as handheld radio transmitters can disrupt systems if shielding and grounding are not robust. When you face intermittent, nonŌĆærepeatable faults that disappear when equipment is opened or slowed down, consider whether interference might be the root cause. Verifying cable routing, shield terminations, and separation between power and signal wiring is a worthwhile line of investigation.

As CTI Electric notes, industrial facilities are increasingly connected through automation networks, industrial internet devices, and cloudŌĆæbased control systems. This connectivity has raised the risk of cyberattacks that cause direct production loss. Ransomware that encrypts critical automation data, unauthorized access through weak passwords or exposed remote entry points, malware introduced via infected portable media, and vulnerabilities in legacy PLC and SCADA systems can all present as sudden, unexplained equipment failures.

During urgent repair, you must keep cyber failure modes in mind. If multiple controllers go offline simultaneously, configuration data becomes inaccessible, or systems behave in ways that do not match any plausible hardware fault, you may be dealing with a cyber incident. The immediate focus still needs to be safe shutdown and containment, but involving your cybersecurity and IT teams quickly can prevent a local incident from turning into a plantŌĆæwide or multiŌĆæsite outage.

The fastest way to minimize production loss in an emergency is to have fewer emergencies and to be well prepared when they do occur. Multiple sources converge on a simple idea: disciplined preventive and predictive maintenance drastically reduce both the frequency and severity of urgent repairs.

Delcon emphasizes using highŌĆæquality industrialŌĆægrade components with higher mean time between failures and evaluating total cost of ownership rather than initial purchase price alone. Although industrialŌĆægrade parts often cost more up front, they significantly reduce unplanned downtime over the life of the system. They also advocate for standardized components and interfaces so troubleshooting is simpler and the variety of required spare parts is minimized. Developing modular system architectures and strategic redundancy in critical areas allows parts of the plant to keep running while a faulty module is serviced.

Develop LLCŌĆÖs guidance on maintenance and upgrades of automated systems highlights the importance of having a dedicated automation maintenance team that owns preventive maintenance, troubleshooting, and coordination with production. That team should build and enforce a preventive maintenance schedule, align maintenance windows with lowŌĆæimpact periods, and manage parts lifecycles and vendor relationships so common wear items and longŌĆælead components are available when needed. Maintenance logs, checklists, and training materials keep knowledge in the plant rather than in a single personŌĆÖs head.

Preventive maintenance, as described by SDC, Hyspeco, JR Automation, and ICA Industrial Controls, includes regular inspections, cleaning, lubrication, calibration, and proactive replacement of wearŌĆæprone components. When this work is done consistently, automated equipment often runs reliably for twenty years or more, compared with similar systems that fail within a few years when maintenance is neglected. That directly lowers the number of urgent repairs you face.

Predictive maintenance takes things further. Delcon, Motion Drives and Controls, Llumin, Twilight Automation, and WorkTrek all discuss using condition monitoring and analytics to detect failures before they occur. That includes sensors that watch vibration, temperature, pressure, acoustics, or energy consumption, feeding data into analytics or artificial intelligence platforms that identify subtle deviations from normal behavior. Twilight Automation cites economic studies showing that predictive maintenance can cut maintenance costs by as much as forty percent compared with reactive approaches, extend machine life by twenty to forty percent, reduce energy consumption by five to fifteen percent, and eliminate a large majority of asset breakdowns, all while delivering average returns on investment around ten times the initial spend.

Llumin and WorkTrek describe how maintenance automation ties this together by integrating condition monitoring, computerized maintenance management systems, and automated work orders. Modern CMMS platforms and predictive analytics can autoŌĆægenerate detailed work orders when thresholds are crossed, complete with issue descriptions, required parts and skills, and urgency levels. WorkTrek notes case evidence where digitized work orders and mobile tools effectively doubled the number of completed maintenance jobs, while Deloitte analysis shows predictive systems cutting maintenance planning time by up to fifty percent and improving uptime by up to twenty percent.

All of this preparation directly affects urgent repair. When you already have sensor histories, clear documentation, upŌĆætoŌĆædate software backups, and an organized spare parts inventory, your time on a lineŌĆædown call is spent solving the problem, not hunting for information or components.

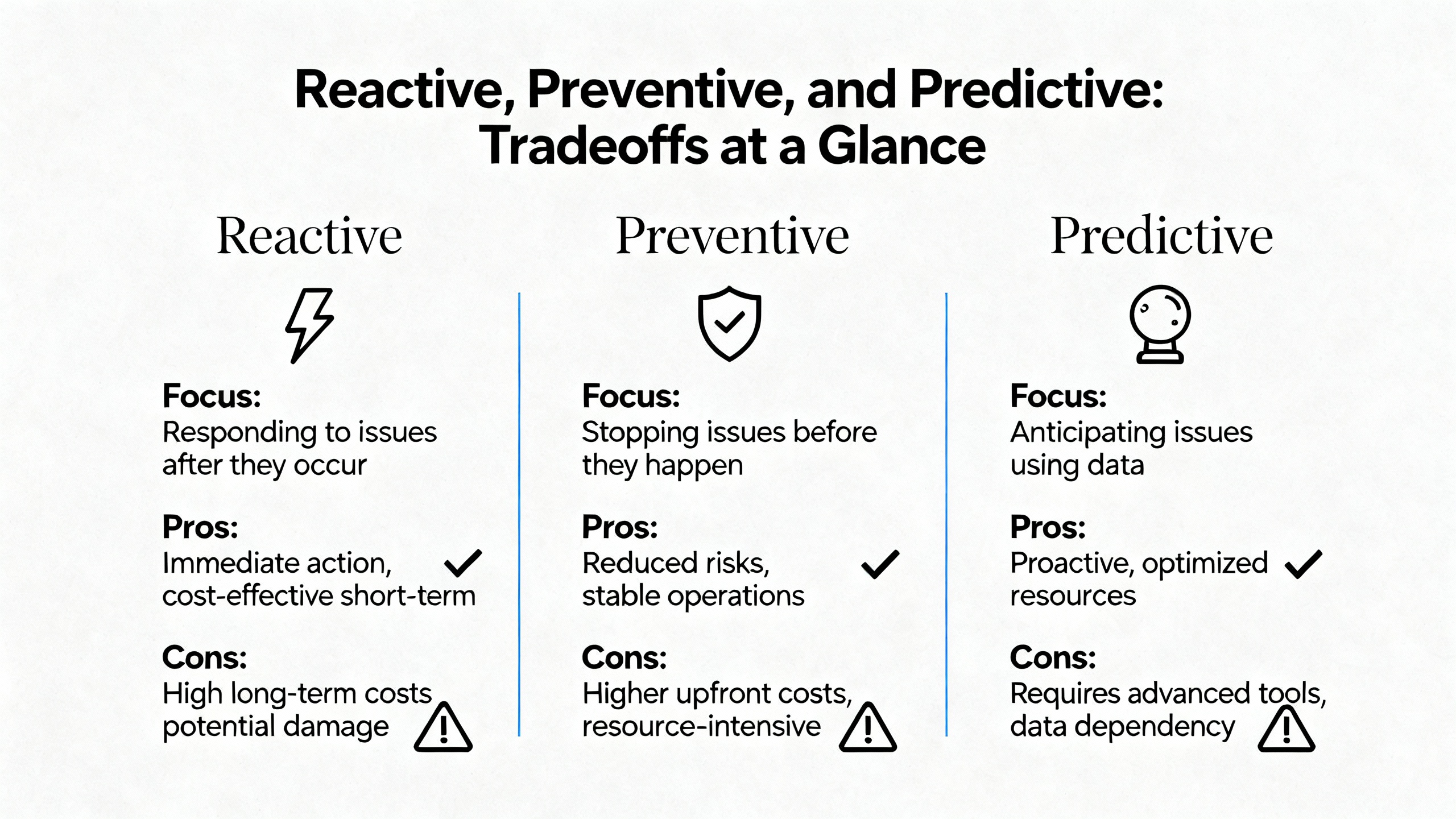

The goal is not to eliminate reactive work entirely; it is to keep it at a manageable level and to make sure it is supported by a strong preventive and predictive foundation. The following table summarizes the main tradeoffs.

| Approach | Main Advantages | Main Risks and Costs | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reactive | Focuses resources on actual failures; simple to start | High downtime cost, stress, emergency premiums, and repeated incidents | Truly random failures, lowŌĆæcriticality assets |

| Preventive | Stabilizes schedules, extends equipment life, improves safety | Can overŌĆæmaintain or miss conditionŌĆæbased failures if intervals are poorly chosen | Most assets where schedules and wear patterns are well understood |

| Predictive | Targets maintenance to real condition, minimizes unplanned downtime, optimizes parts inventory | Requires sensors, data infrastructure, analytics expertise, and upfront investment | Critical and expensive assets, bottleneck equipment, safetyŌĆæcritical systems |

Embedded.com and YASH Technologies both emphasize that the best results come when maintenance automation initiatives are treated as strategic investments with clear goals and business cases, focused first on critical assets with high capital cost, high repair cost, or direct impact on revenue, safety, quality, or regulatory compliance. They recommend selecting sensors based on clearly defined failure modes instead of deploying technology for its own sake, and using advanced CMMS platforms for continuous monitoring, alerts, and timeŌĆæseries analysis rather than sporadic spot checks.

Turning these ideas into a program that consistently minimizes production loss requires more than a few good technicians. It requires process, tools, and culture.

First, define what constitutes an automation emergency in your facility. KnobelsdorffŌĆÖs distinction between an emergency stop and a cycle stop is useful here. Map out which lines and machines are truly critical in terms of revenue and safety. Use guidance from YASH Technologies and Embedded.com to perform an asset criticality assessment that considers capital value, repair cost, and impact on operations and compliance. This helps you set escalation rules so the right people are involved quickly when a highŌĆæimpact system fails.

Second, formalize your troubleshooting methodology. Train technicians on the sixŌĆæstep process outlined by DigiKey TechForum and practice it during nonŌĆæcritical events so it becomes natural in real emergencies. Incorporate SOPs, service logs, and checklists, as recommended by DigiKey and Develop LLC, so symptom recognition and elaboration are driven by consistent questions and observations. Require that every urgent repair ends with a short failure analysis and documentation in the CMMS.

Third, organize parts and documentation around urgency. Use insights from SDC, JR Automation, and Develop LLC to maintain a spare parts inventory that covers common wear components and critical, longŌĆælead items for key equipment. Ensure that software backups, wiring diagrams, safety documentation, and vendor contact information are stored centrally and accessible around the clock. When a PLC fails or an industrial PC dies, having a validated program backup and a knownŌĆægood spare on the shelf turns a catastrophic outage into a short interruption.

Fourth, introduce predictive and automated maintenance where it matters most. Following Llumin, WorkTrek, Twilight Automation, and Motion Drives and Controls, start with a focused pilot on a handful of critical assets that are known sources of downtime. Instrument them with appropriate sensors chosen according to the failure modes identified, integrate data into your CMMS or analytics platform, and configure conditionŌĆæbased work orders. Use the results of that pilot to refine your approach and build a business case for expansion, emphasizing reductions in urgent repair frequency and downtime hours.

Finally, invest in people and culture. Develop LLC and ICA Industrial Controls both emphasize ongoing training and knowledge transfer so that only qualified personnel perform maintenance and troubleshooting, and so reliance on external support declines over time. Llumin and WorkTrek highlight change management and handsŌĆæon learning as key to successful adoption of maintenance automation. Encourage technicians to share lessons from each emergency repair during brief reviews and to update SOPs and checklists accordingly. Over time, your urgent repair program becomes not only a response mechanism but a continuous improvement engine that drives emergencies down.

The decision hinges on safety, production impact, and risk of further damage. If continued troubleshooting presents safety risks or the fault is clearly within a noncritical subsystem, it may be better to implement a safe, engineered temporary workaround that preserves core operation while you plan a permanent fix during scheduled downtime. Embedded.com and YASH Technologies recommend defining these rules in advance as part of your asset strategy, so you are not making ad hoc decisions under pressure.

The quickest gains usually come from better organization and process rather than new hardware. Based on DigiKey TechForum, Develop LLC, SDC, and JR Automation, focus on writing and using SOPs, maintaining accurate service logs, keeping a minimal but thoughtful spare parts inventory, training technicians on a structured troubleshooting approach, and centralizing documentation. These steps often pay back quickly in reduced diagnostic time and fewer repeated failures.

Predictive maintenance is most valuable on assets that are both critical and prone to failures that can be detected through measurable conditions such as vibration, temperature, or electrical signatures. Twilight Automation and Llumin show that on these assets predictive approaches can dramatically reduce unplanned downtime and maintenance costs while providing strong financial returns. If a single failure on a machine can cost hundreds of thousands of dollars in lost output, and there is a clear physical signal that degrades before that failure, predictive monitoring is usually justified.

Modern industrial automation plants will always experience surprises, but they do not have to live in constant crisis. When you treat every urgent repair as both a controlled emergency and a learning opportunity, supported by structured troubleshooting, solid maintenance fundamentals, and smart use of data and automation, you can keep your lines running, protect your people, and turn ŌĆ£line downŌĆØ events from existential threats into manageable interruptions.

Leave Your Comment